Living in Lombard Street, by 1851 John Peake, then operating as a furniture broker (which usually meant a dealer in second hand goods) had a large family. Born in Lichfield in 1798, his wife Charity had been born in Exeter in 1806. Between them they had nine children: Edward (b. 1831), a writing clerk; Ann (b.1834); Peter (b. 1837), a tailor’s apprentice; Thomas (b. 1838); Elizabeth (b.1842); Charity (b.1842); Philip, (b. 1844); Steven (b. 1847); and Arthur (b. 1850).[1] With the exception of Elizabeth, Charity and Philip, who were born in Barton, Staffordshire, all the children were born in Lichfield.

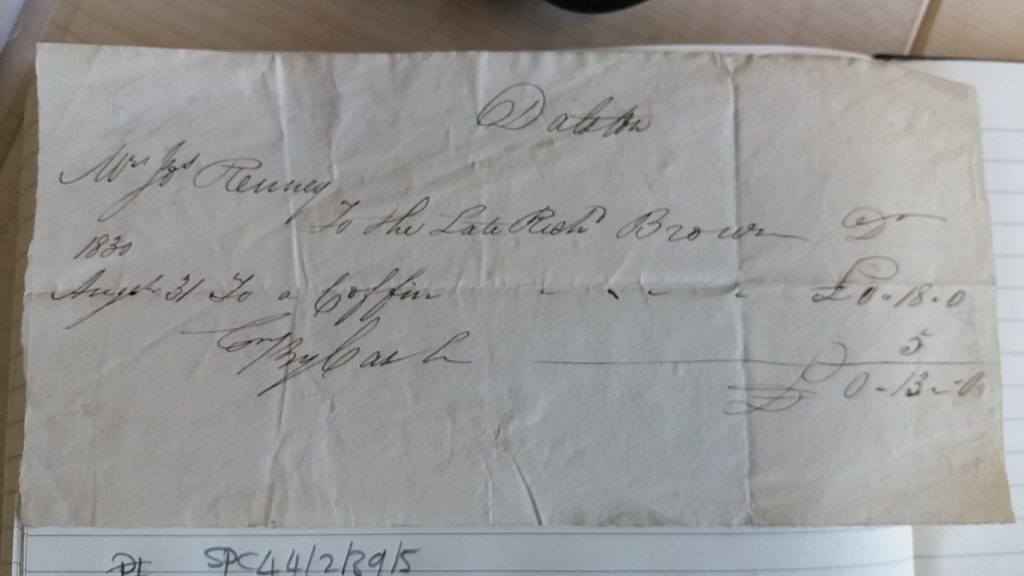

This was his second marriage. The Birmingham Journal in 1826 reported the death of ‘Mrs Peake, wife of Mr John Peake, ironmonger, of Market Street, Lichfield’.[2] She was 32.

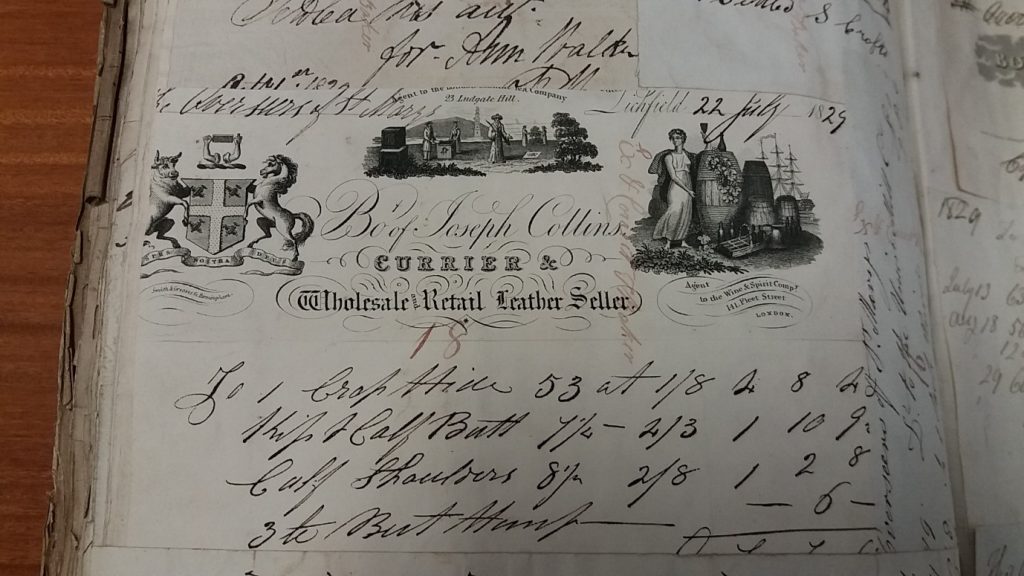

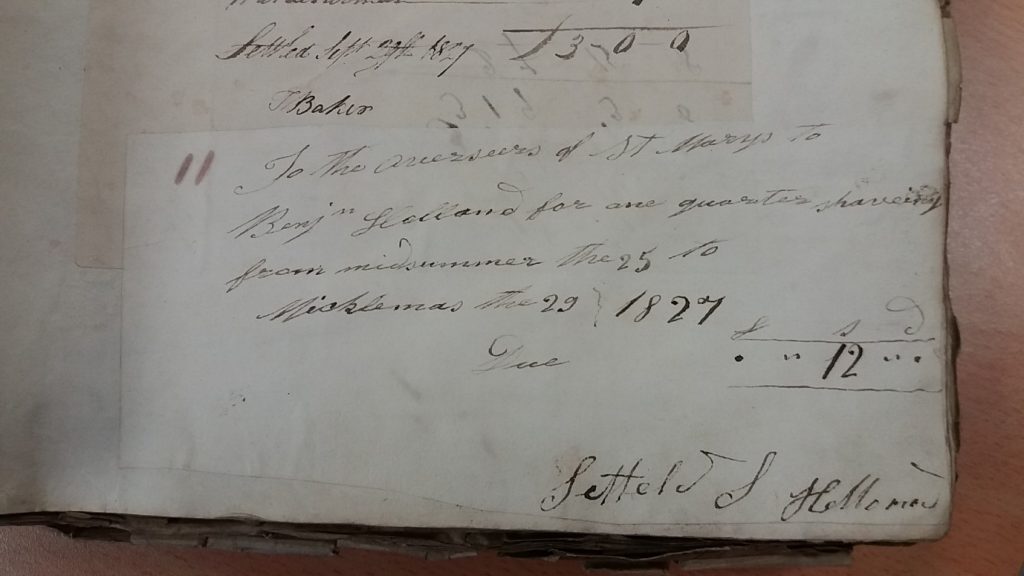

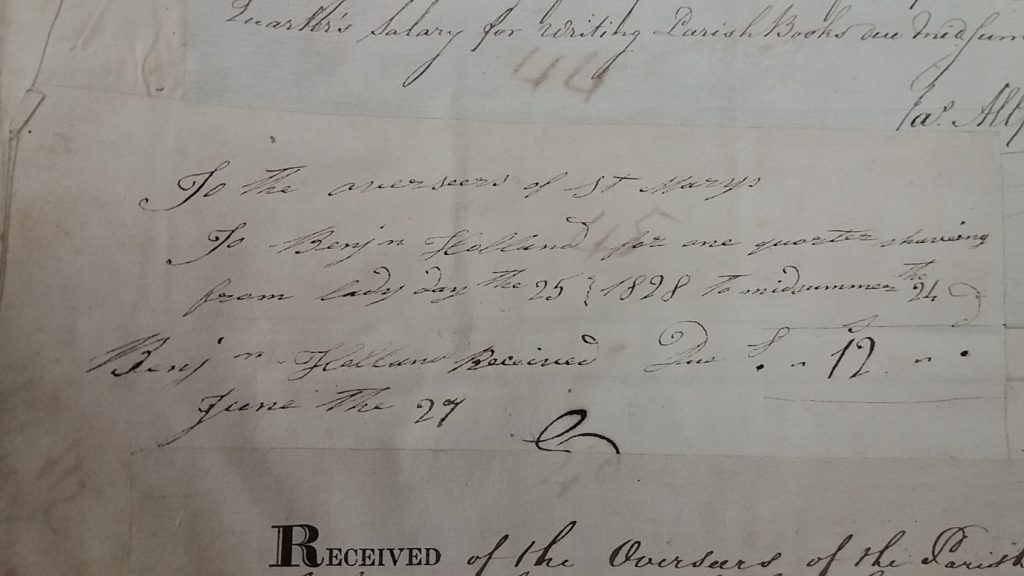

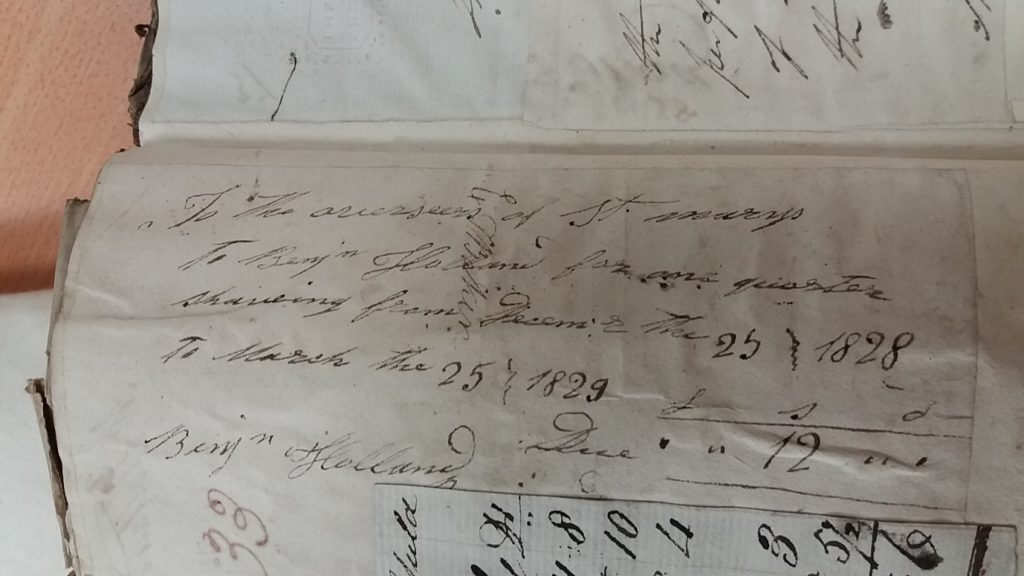

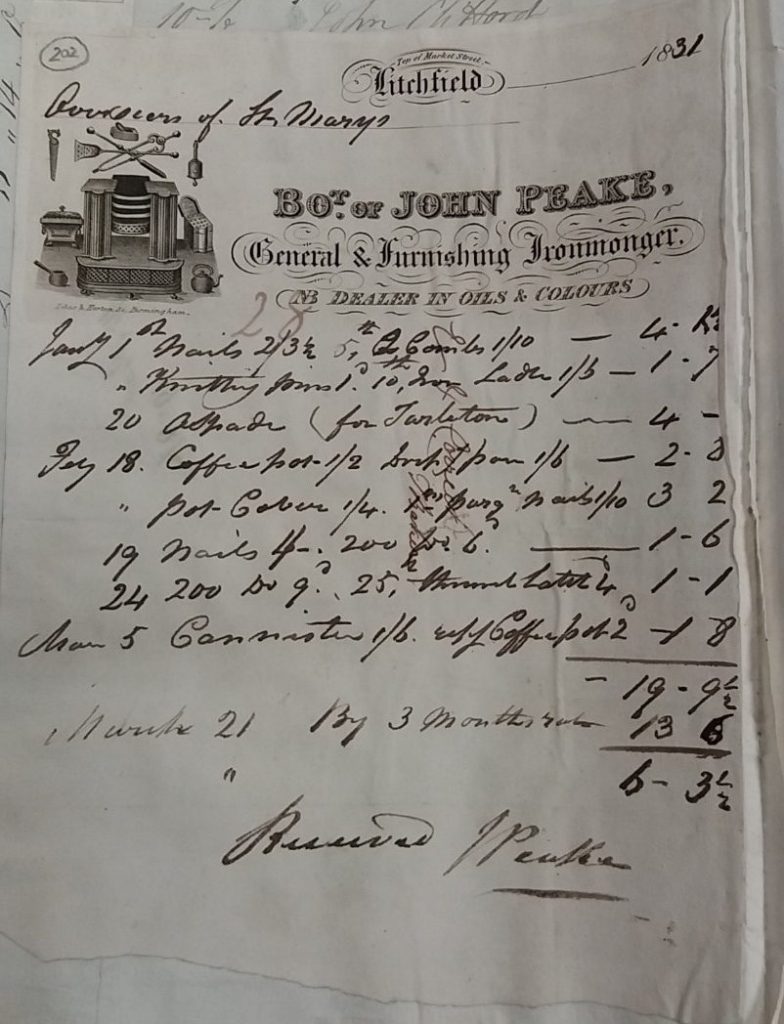

Listed in Pigot’s 1828 directory and in White’s 1834 directory as resident in Market Street, Peake supplied the overseers St Mary’s with ironmongery such as nails, coffee pots, and canisters, but, as his bills show, he was also a colourman or dealer in paints and oils.[3]

An advert in the Staffordshire Advertiser in 1829 reveals more about Peake’s business.[4] He was a bell hanger, lock and jobbing smith. His stock, offered at low prices with a five per cent discount for ready money, included cutlery, 52-piece table services, grates, lamps, fenders, fire irons, Britannia metal and ‘japanned’ goods, locks, bolts, hinges, nails, and screws. The same advert also announced that Peake was seeking ‘A respectable youth’ as an apprentice.

Things started to go wrong in July and August 1837 when a fiat of bankruptcy was issued against Peake and his business partner Thomas Hall.[5] They were required to present themselves before the bankruptcy commissioners on 7 September and again on 6 October at the Old Crown Inn, Lichfield. There they were to ‘make a full discovery and disclosure of their estate and effects’, and their creditors were ‘to come prepared to prove their debts’. Those indebted to the bankrupts, or who had any of their effects, were to contact solicitors Messrs. Bartrum and Son, of Old Broad Street London, or Messrs. E. and F. Bond, solicitors, Lichfield. The Bonds also undertook work for the parish of S. Mary’s.

At the end of September the Birmingham Journal announced the immediate disposal of the stock-in-trade, counters, shelves, and implements of Messrs John Peake and Co. ‘ironmongers, braziers, and tinmen in Market Street’.[6]

A dividend was paid to creditors in February 1838 at which point creditors, who had not already proved their debts, were requested to attend the meeting at the Old Crown to prove their claim, or be excluded the benefit of the dividend. Claims not proved at the meeting were to be disallowed.[7]

A certificate of discharge for Peake and Hall was issued in March 1838.[8] This allowed them to pursue business once again. This, however, was not the end of the issue. In December 1838, creditors were informed of a meeting to take place, once again at the Old Crown, with the assignees of the bankrupts’ estate on 21 January 1839.[9]

At the meeting the creditors were to assent or dissent from the assignees commencing a law suit against the trustees and managers of Lichfield’s Bank for Savings and against John Peake, Thomas Hall, and others for the purpose of ‘recovering certain sums of money, now in the hands of the said trustees and managers of the said Bank’. The assignees claimed that the money formed part of the separate estate of Thomas Hall. The creditors were also asked to assent or dissent from allowing the assignees to submit to arbitration in the matter. The matter rumbled on.

Six years later in December 1844, it was announced that John Balguy, a commissioner authorized to act in bankruptcy cases would sit in January 1845 at the Birmingham District Court of Bankruptcy, in order to ‘Audit the Accounts of the Assignees of the estate and effects’ of Peake and Hall.[10]

Alongside his wife, in 1861 were their sons Stephen (sic), an architect’s clerk, aged 14; and Arthur; and their grandson, Charles Peake, aged eight.[11] By 1871 Peake’s household in Bore Street was reduced in size again. Living with himself and his wife were their daughter Charity and her husband George Smart who had been born in Essex.[12]

[1] TNA, HO 107/2014, Census 1851.

[2] Birmingham Journal, 4 February 1826, p.3/5.

[3] Pigot and Co., National Commercial Directory [Part 2:] for 1828–29 (London and Manchester: J. Pigot and Co., 1828), p. 716; William White, History, Gazetteer and Directory of the County of Staffordshire and of the City of Lichfield (Sheffield: 1834), p. 160.

[4] Staffordshire Advertiser, 28 March 1829, p. 1/1.

[5] London Gazette, 25 August 1837, p. 2261; 10 December 1844, p. 5139.

[6] Birmingham Journal, 30 September 1837, p. 5.

[7] London Gazette, 13 February 1838, p. 333.

[8] Globe, 8 March 1838, p. 3.

[9] London Gazette, 28 December 1838, p. 3002.

[10] London Gazette, 10 December 1844, p. 5139.

[11] TNA, RG9/1972, Census 1861.

[12] TNA, RG 2913/37, Census 1871.