What was The Poor Law?

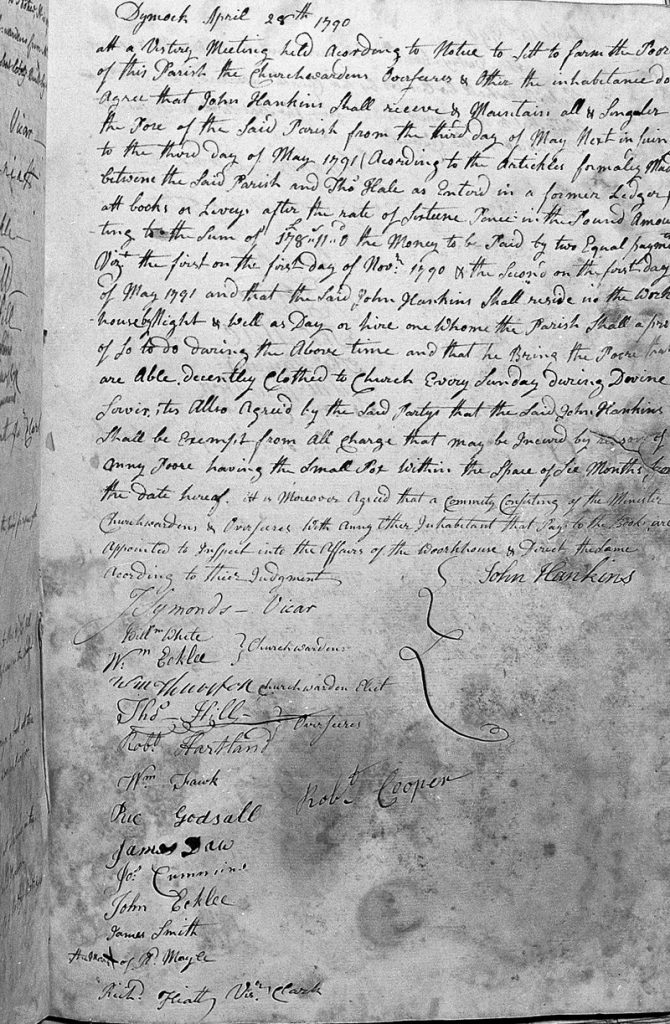

The Old Poor Law in England and Wales, administered by the local parish, dispensed benefits to paupers providing a uniquely comprehensive, pre-modern system of relief. The law remained in force until 1834, and provided goods and services to keep the poor alive. Each parish provided food, clothes, housing and medical care. This project will investigate the experiences of people across the social spectrum whose lives were touched by the Old Poor Law, whether as paupers or as poor-law employees or suppliers.

Workhouses

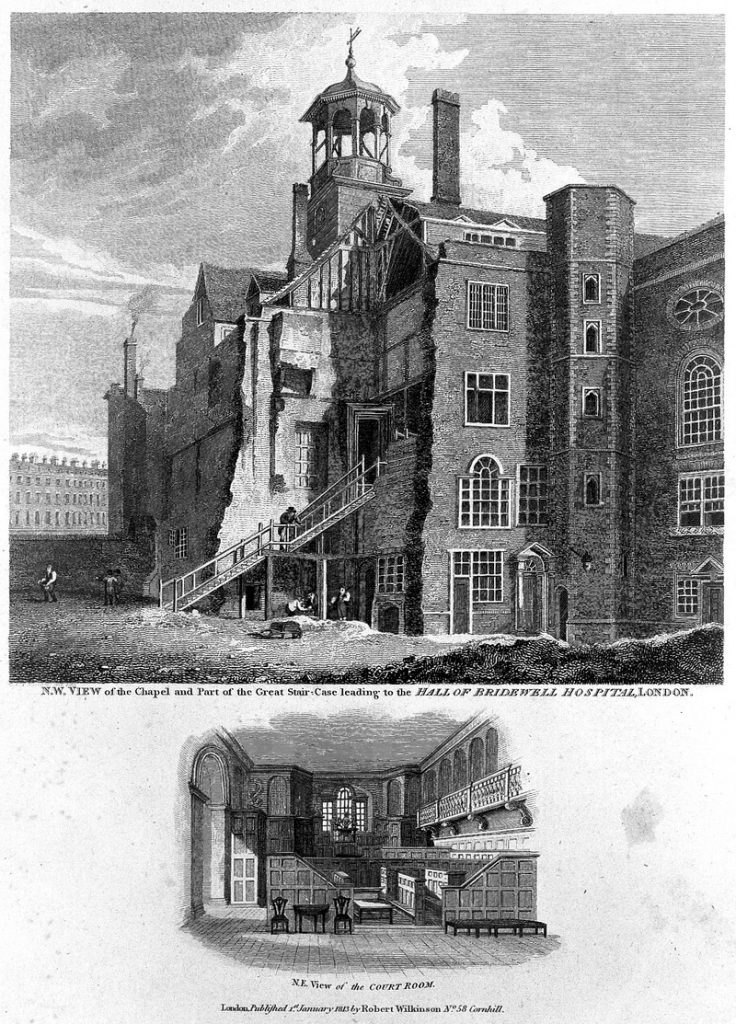

English workhouses have their origins in sixteenth-century European ideas, when anxieties about vagrancy and unemployment prompted the generation of compulsory work schemes. The first experiment in this vein in the British Isles was founded at the former palace of Bridewell in London during the 1550s, where food and lodging were offered in exchange for labour. Provincial towns opened their own ‘bridewells’ from the 1560s onwards.

The Elizabethan poor laws of 1598 and 1601 incorporated the idea of setting the poor to work, to be funded by an annual local tax. Parishes were permitted to acquire a stock of materials for employing paupers. In the case of textiles, for example, a parish might buy wool and then insist that poor people spin it into yarn in exchange for a small cash payment or other benefit. Most parishes that tried to apply this policy quickly found it too expensive to maintain. The money earned from selling the finished produce, such as spun wool, rarely covered the costs of the materials. The law had not specified a location for work, and parishes did not try to supply a single workplace for this activity.

The second half of the seventeenth century saw the rise of a new ideology, that of setting the poor to work at a profit. It was thought that proper management of the right sort of work would not only cover costs but also remove the need to raise a local tax. This encouraged some towns to apply for an individual Act of Parliament to become a Corporation of the Poor. Corporations allowed multiple urban parishes to work together to raise a tax and run a large institution collectively. Bristol was the first town to take up this option, and Exeter was the first place to construct a large, purpose-built workhouse.

It soon became apparent to Corporations that it was not possible to render the workhouse poor self-supporting. The sorts of people who required relief – the young, the elderly, the sick or disabled – were often not well-placed to undertake work of any kind. Nonetheless, the hope of finding the right formula for making the poor profitable remained beguiling, and parishes continued to establish workhouses on this basis throughout the eighteenth century. A workhouse policy was promoted early in the century by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, or SPCK, and the process of opening a workhouse was made easier by a general Act of Parliament in 1723. This Act allowed parishes to buy, rent, build or collaborate with each other to run workhouses. The Act also introduced a new element to the use of workhouses, because it enabled parishes to insist that poor people enter them, if they wanted to receive parish poor relief (rather than receiving cash or other benefits in their existing homes). This workhouse ‘test’ was applied inconsistently, with some places never making relief dependent on workhouse entry and others trying to impose the rule sporadically. Nonetheless, it became a very important precursor to the insistence on delivering relief only in workhouses, that dominated ideas from the 1820s onwards.

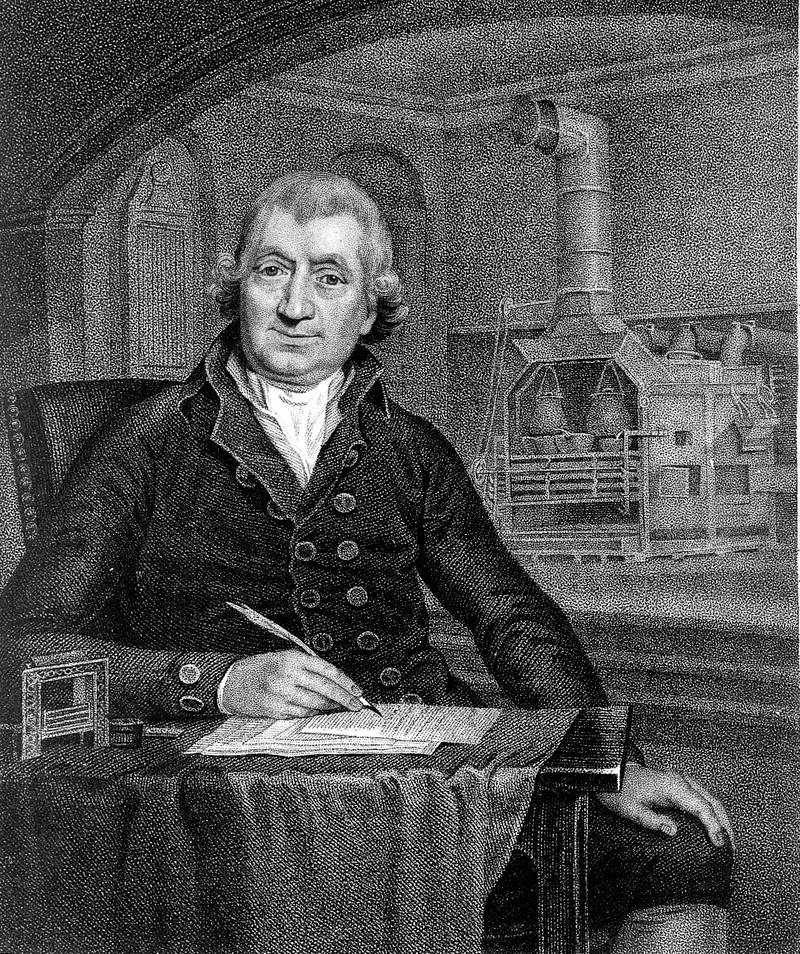

By 1800 it was no longer thought feasible to make the workhouse poor generate a profit, but a new goal emerged to render the poor as efficient and cost-effective as possible. Benjamin Thompson, an American known to history as Count Rumford, devised a workhouse diet based around soup that yielded the maximum number of calories for the lowest possible cost. After 1815 and the economic disruption that followed the Napoleonic wars, sentiments towards the poor became more harsh. Selected parishes made their workhouse as punitive as possible: Southwell in Nottinghamshire followed this policy, and became a model for the ‘reformed’ workhouses established after 1834.

Many parishes made use of workhouses in the approximate century 1723-1834 but not all of them were influenced by these ideas about workhouses, or applied them consistently. A parish might begin with the intention of delivering all poor relief in the workhouse, and setting the poor to work, but would typically lose enthusiasm for both of these requirements. Instead workhouses became places to accommodate the elderly poor, and offer nursing to them at scale, or to give homes to the young and orphaned poor before they were apprenticed at parish cost. By 1776 there were around 2000 workhouses across England, with some in every county. The majority were fairly small-scale, housing 20-50 people, and did not have stringent rules. Some paupers even used them flexibly, seeking admission to their local workhouse in winter or in times of unemployment or sickness and moving out as opportunities came their way for independence.

Therefore, it should be no surprise that this project has already revealed a number of different parish approaches to workhouse management. Volunteers in Staffordshire have contrasted the Uttoxeter workhouse, which set adult men to work in a brickyard, with the Tettenhall workhouse that held around 30 residents at one time who tended to be elderly or very young. Cumbria volunteers have studied parishes with or without workhouses, and archival volunteers in East Sussex working on East Hoathley have encountered no workhouse so far. This level of variation is what we would have expected, but the vouchers allow us to look in much greater detail at the way workhouses operated for their resident poor and for their local economies. Even when there was no work in workhouses, they represented an important component of parish relief.

Alannah Tomkins