The Covid-19 lockdown has had many of us setting about de-cluttering and tidying at home. For me a principal tidying target has been the collection of notebooks in which I’ve recorded snippets of information and jottings from research at Staffordshire and Lichfield record offices. Going through one of these a few days ago to make sure I had entered up everything on my laptop in a more organised way, I found some brief notes I’d been trying to track down for ages. These concerned a Richard Ward, shoemaker and the source was Burton St Modwen vestry minutes [1].

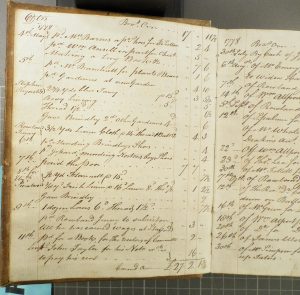

On 9 July 1817 these minutes reported that it had been resolved to bring Richard Ward into the workhouse to be employed in making and mending shoes and that his goods be redeemed. On 1 May 1822 the minutes reported that Richard Ward of Alrewas be allowed £5 to assist him in his rent, he being unwell at times. This money was sent to him by a courier. On 16 April 1823 Richard Ward of Alrewas was supplied with some bedding. Now this was a puzzle. Richard was born in 1789 in Streethay, just north of Lichfield. Parish register entries indicate that his family gradually moved northwards to Fradley and then Alrewas. So why was Burton parish a good eight miles away taking responsibility for him? Clues come from the Alrewas parish register [2] where his marriage by licence to Elizabeth Wootton in 1811 indicates he was “of Burton” and this is confirmed by the associated marriage bond and allegation. [3] He may have gained a settlement in Burton, possibly through apprenticeship.

Resolving a person’s settlement could be a fraught business if they sought parish relief and the overseers suspected another parish should or could be liable. It could also be expensive for the parish if a challenge was disputed. Among the project vouchers submitted by lawyers there are many, many examples of the bills incurred by overseers to resolve matters of settlement.

Sadly, overseers’ vouchers for Burton have not found their way to Staffordshire Record Office, so it is not possible to delve further into Richard’s shoe making and mending while in the parish workhouse in Hawkins Lane. Likewise, vouchers for St Michael’s parish in Lichfield (which includes Streethay) have not survived. Vouchers for Alrewas parish were processed for the project and these show that it did not have its own workhouse but sent paupers over to nearby Rosliston in south Derbyshire. [4]

At one of the workshops held at Stafford in connection with the project, Dr Joe Harley set out how useful pauper inventories could be as sources of information. His talk drew on research published in 2015. [5] His paper sets out evidence for the able-bodied poor using the workhouse as a short-term survival strategy. This may well have been the case for Richard.

Overseers’ vouchers for Uttoxeter [6] show that the constable was ordered on 15 Feb 1832 to grant relief to William Breeze to redeem his bundle of clothes and resume his journey to London, and that Joseph Barnes was paid 8 shillings on 20 March 1835 to redeem four articles belonging to Sarah James. Likewise overseers’ vouchers for Tettenhall [7] show payments of 2s to Francis Taylor on 24 Feb 1831 to redeem James Billingsley’s coat, of 6d on 28 June 1832 to redeem Maria Williams’ shawl and of 19s 2½d on 29 June 1832 to redeem Thomas Williams’ coat and for an inquest .

Richard Ward’s experience of Burton workhouse did not put him off returning to the town after his youngest child was born in Alrewas in 1825. It is possible to track the family living in Burton through the 1841, 1851 and 1861 censuses until Richard died in 1869 and was buried in Burton’s new municipal cemetery at Stapenhill. Two of his sons (William and Richard) lived out their lives in Burton, too. I have visited all their graves and stood the proverbial six feet above. Richard was my 4xgreat grandfather and William my 3xgreat grandfather. I know lots about their various doings.

During Dr Pete Collinge’s Zoom-based talk to the Erasmus Darwin Society on 28 Jan 2021 on ‘Food and the Georgian pauper: evidence from Sandford Street Workhouse Garden , c. 1770-1834’, a lady attending provided illuminating and fascinating information about cottages on Sandford Street in Lichfield and on the Sedgewick family from her own family memories. It never ceases to amaze me just what detail emerges from studying the overseers’ vouchers and other records in connection with this project and the buzz of excitement that comes from connecting with one’s own family.

[1] SRO, B12, Burton St Modwen Vestry minute book, 1805-1840

[2] SRO, D783/1/1/6 Alrewas All Saints, Register of marriages

[3] SRO, PAL/C/6,7/1811/Ward, Alrewas marriage bond and allegation

[4] SRO D783/2/3 Overseers’ vouchers for Alrewas

[5] Harley, J., ‘Material lives of the poor and their strategic use of the workhouse during the final decades of the English old poor law’. Continuity and Change, 30, (2015), pp. 71-103 doi:10.1017/S0268416015000090

[6] SRO, D3891/6/37/12/1 and D3891/6/41/7/21 Overseers’ vouchers for Uttoxeter

[7] SRO, D571/A/PO/65/13; D571/A/PO/69/71; D571/A/PO/69/173 Overseers’ vouchers for Tettenhall