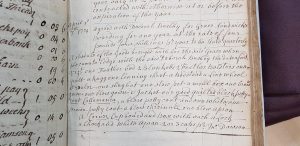

Overseers’ vouchers sometimes contain bills sent by landlords of public houses and coaching inns. Inns were often the locations of parish business, or places where those on parish business took refreshments.

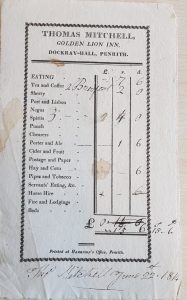

Parson and White’s 1829 trade directory listed fifty-five hotels, inns and taverns in Penrith, including Thomas Mitchell’s Golden Lion, Dockray Hall.

In 1814, the overseers were billed by the parish representative for the following expenses at the Golden Lion:

Eating £0 7s 6d

2 Breakfasts £0 2s 0d

Negus Spirits £0 4s 0d

Porter and Ale £0 1s 6d

and Hay and Corn for the horses £0 0s 6d

Negus is made from wine, often a fortified one such as port, to which is added hot water, citrus fruits like oranges or lemons, spices like nutmeg, and sugar.

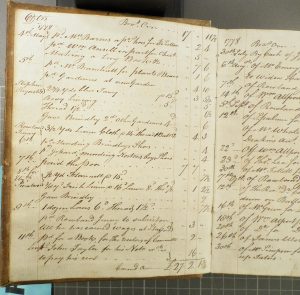

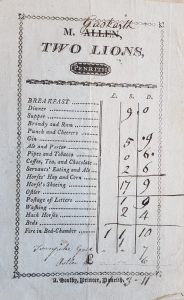

An undated bill from Gasgarth’s Two Lions listed the following items:

Dinner 9s 0d

Brandy and Rum Punch and Cheerers Ale and Porter 2s 9d

Pipes and Tobacco 0s 6d

Horses hay and Corn Horse Shoeing 17s 9d

Postage of Letter 1s 9d

Hack Horses 2s 4d

Turnpike Gate 1s 7d

The bill was printed by A. Soulby

A bill was also submitted by a parish official to the overseers of Threlkeld who had been to the Wilkinsons’ Griffin Inn (see M. Dean, ‘Wilkinson’s Griffin Inn, Penrith’, https://thepoorlaw.org/wilkinsons-griffin-inn-penrith/).

Sources

Parson and White, Directory of Cumberland and Westmorland, Furness and Cartmel (1829)

Cumbria Archive Service

SPC21_8_11_62, Threlkeld, Thomas Mitchell, 22 June 1814

SPC21_8_11_74, Threlkeld, M [Allen crossed out] Gaskarth TWO LIONS, undated, c.1814