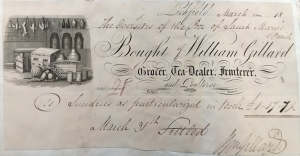

SRO, LD20/6/6/400, Overseers’ Vouchers, Lichfield St Mary, William Gillard, 31 March 1832

William Gillard’s bill for ‘sundries as particularized in book’, is not very revealing about the goods he supplied to St Mary’s Lichfield. From the printed billhead, however, we learn that he was a grocer, tea dealer, fruiterer and poulterer who also sold pickles, vinegars, sauces and Stilton cheese. The illustration of a shop interior shows the products he sold, how they were stored and displayed on shelves, in nests of drawers, in bottles, canisters, jars, boxes and chests. The use of a printed billhead also reveals that Gillard aimed to supply not just the poor but also those further up the social scale and indicated the sort of service they could expect.

William Gillard, baptised on 14 August 1785, was the son of Thomas Gillard of Lichfield.[1]

At the time of the Census in 1851, Gillard was living in St John Street with his wife Mary.[2] He was described as Crier of the Court of the General Quarter Sessions of the Peace. Pigot’s directory of 1828–9, listed him as grocer, tea dealer and keeper of a register office for masters and servants with premises in Boar Street.[3] Mary was born in Morpeth, Northumberland.

William Gillard’s will (giving his address as St John’s Cottage), made ample provision for his wife, provided that she did not remarry after her husband’s death.[4] Part of his personal estate was to be sold and the money invested in stocks and securities to provide her with an annual income. The trustees of William’s estate, his son Charles and Richard Walthow were to permitted to sell part of his estate only with the written consent of his widow. Mary was given a lifetime interest in William’s household goods, plate, china, linen, pictures, books, and chattels.

William and Mary’s children received the following:

Mary Ann, the wife of William Mander, £250.

William Taylor Gillard, £60.

Elizabeth, the wife of Alfred Eggington, £250.

Charles Gillard, £60.

Maria, the wife of Thomas Pear, £250.

Jane, the wife of John William Proffit, £250.

Henry, £80.

The bequests to William’s daughters were independent of their husbands.

Following the death of their mother, any moneys, stocks and securities were to be divided equally among the children.

Gillard died aged sixty-eight and was buried in St Michael’s on 17 January 1854.[5]

[1] SRO, D20/1/3, Lichfield St Mary baptisms and burials.

[2] TNA, HO 107/2014, Census 1851.

[3] Pigot & Co., National Commercial Directory, 1828–9, pp. 716–7.

[4] SRO, P/C/11, William Gillard.

[5] SRO, St Michael’s Parish Register.