Phineas Stone has only one voucher in our project dataset, but he snagged our interest owing to the disjunction between his occupation, as a gunlock filer, and the typical purchases of the overseers of the poor. What business did they have with a refiner of gun parts?

The parish overseers paid Stone for a ‘voice’ or vice weighing 36lb on 3 February 1789. This equipment was for the use of Jonathan Addock or Haddock, and was costed by weight. At three pence per pound, the total cost of the vice came to nine shillings. Therefore the parish was buying a tool for use by Haddock, presumably to enable him to earn money. Unfortunately we have no clues as to what Haddock usually did for a living. He was a some-time pauper and who needed parish help to pay the burial fees when his wife Ann died 1793, but otherwise we are not really any wiser. We can only speculate that, like many men in the parish and the wider West Midlands, Haddock was engaged in metalworking of some kind.

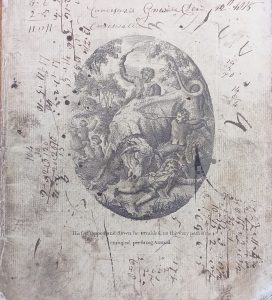

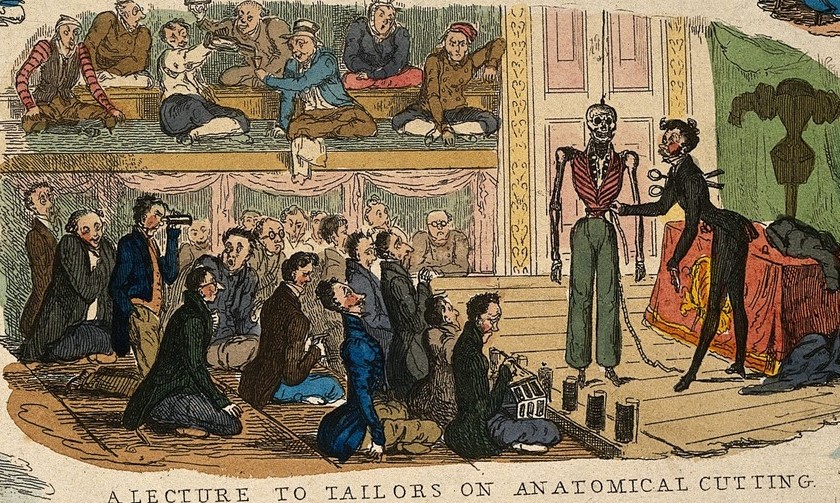

A rather tidy workshop showing the manufacture of metal buttons in the Netherlands: engraving by Prevost c.1751-72 image courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The Stone family fortunes were also in decline, but not so drastically as to require the need for parish assistance in the vouchers we have catalogued. Shortly before Phineas died in 1796, his son Phineas (1775-1811) got married and had a son of his own, unsurprisingly baptised Phineas (1797-1837). Of the three men named Phineas, all of whom were lockfilers, the eldest left an estate worth under £300, but his son was worth under £100 at the time of his death in 1811. The youngest Phineas was killed in 1837 by the throwing over of a coach.

Sources: baptisms of 1 May 1775, 12 March 1797, and 19 January 1834, marriage of 7 September 1796, plus burials of 30 August 1793, 6 December 1796, 4 July 811, and 8 August 1837, all Wednesbury St Bartholomew. Probate for the will of Phineas Stone granted 1797. Probate for the will of Phineas Stone granted 1811. SRO D 4383/6/1/9/2/95 Wednesbury overseers’ voucher 1789; D 4383/6/1/9/3/111/4 Wednesbury overseers’ voucher 1793.