George Fieldstaff was someone who benefited from the Old Poor Law as a labourer who was employed for his strength but also as a supplier of accommodation. Unusually, for histories of the Old Poor Law, he spans the boundary of pauper-ratepayer.

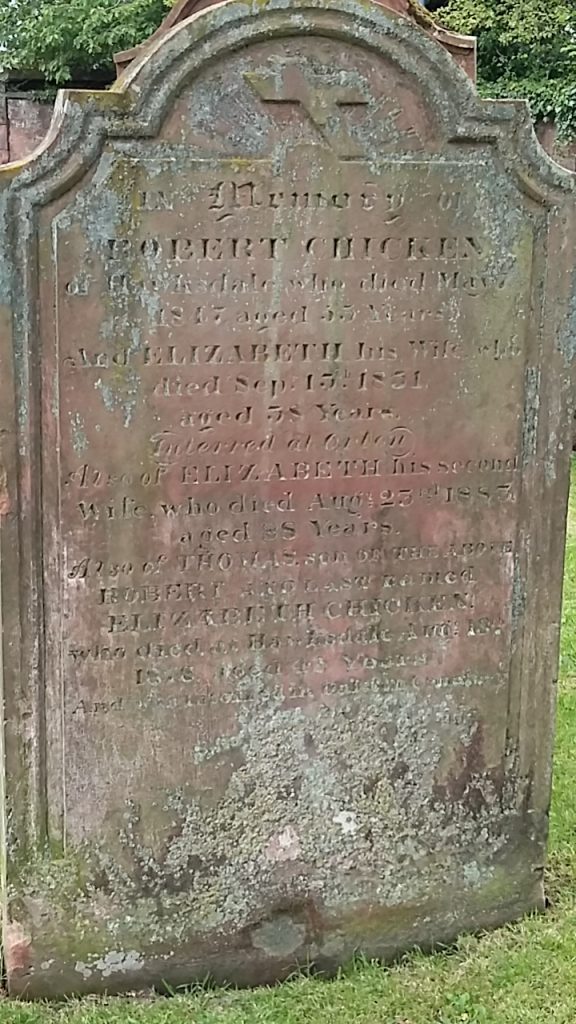

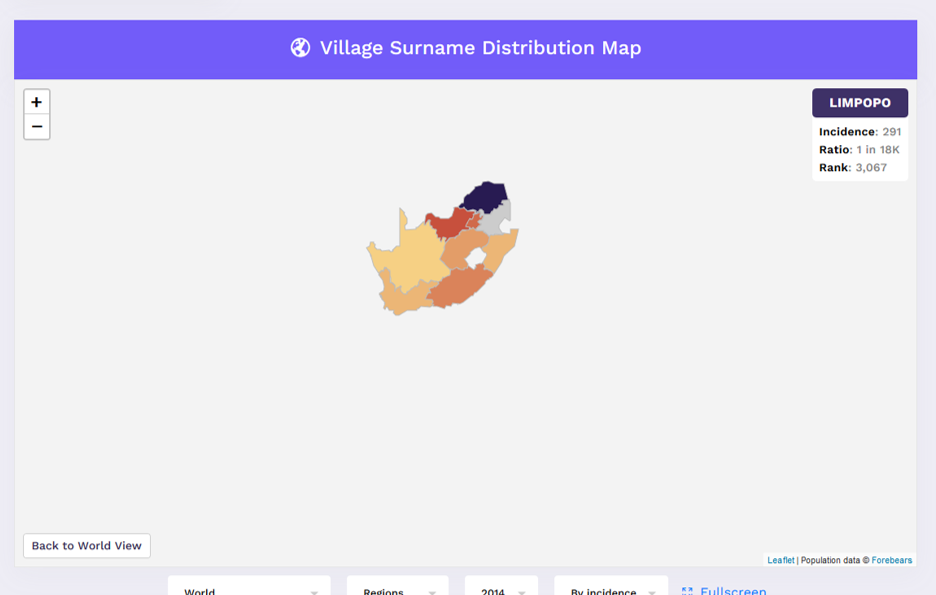

He was baptised George Fieldstead in 1796, the son of James and Sarah Fieldstead, but all later census entries suggest that he was up to ten years old at the time of baptism. The family’s surname is given variously as Fieldstad and Fieldstid before finally settling on Fieldstaff in the 1820s. George married Elizabeth Bacon in 1820 and the couple had at least two children (Elizabeth and William), but he became a widower in 1824. He then married Maria Brough (born c. 1786), who was herself a widow, on 17 January 1825, for which event neither spouse signed their name. The second marriage produced at least one daughter, Martha, although not until 1835.

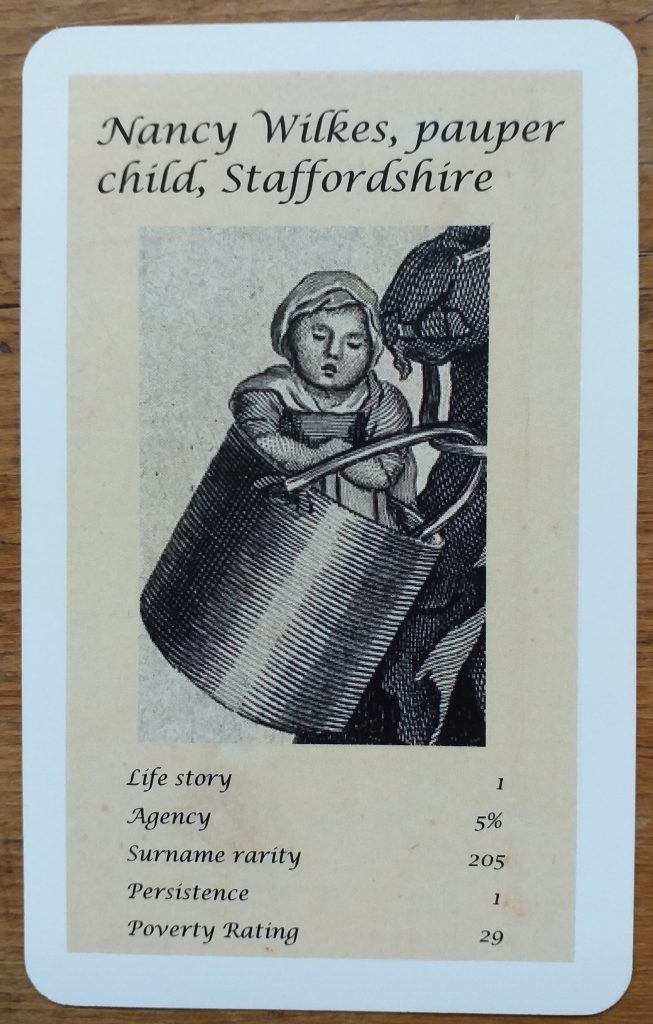

Censuses later describe Fieldstaff as an agricultural labourer and hawker, but after the death of his first wife he needed to turn to the parish for help and spent time as an inmate of the Uttoxeter workhouse. By 1829 he was being employed in the workhouse brickyard, presumably cutting clay or hefting bricks in the manner of an industrial labourer, because he was paid for his work in May 1829. In July 1829 was prosecuted at the Staffordshire quarter sessions for refusing to work while in the house but was paid again after he had resumed work in September of the same year.

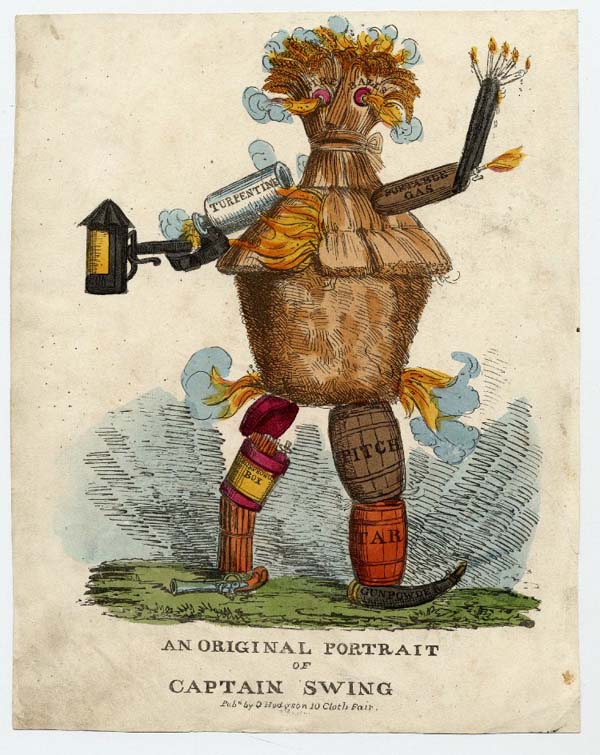

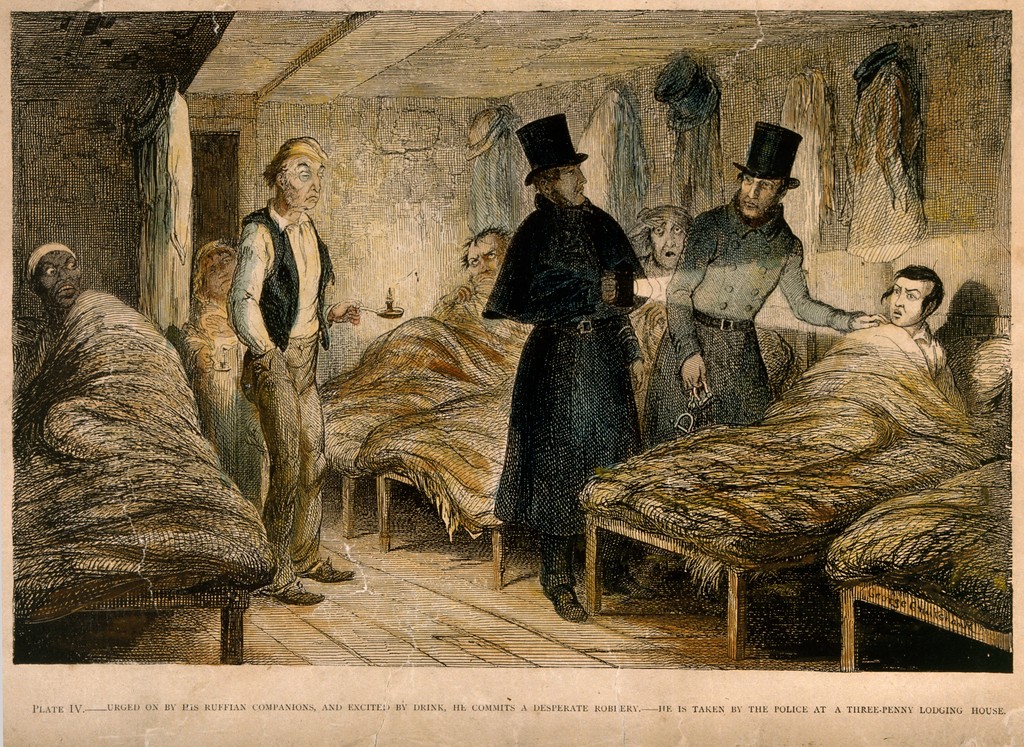

Census labels notwithstanding, the most characteristic and persistent aspect of his employment history (discernible at this distance) is his keeping of a lodging house. George Fieldstaff had escaped the workhouse by 1832, as between August 1832 and March 1833 Uttoxeter parish paid repeatedly to lodge itinerant people at his house on Smithy Lane, later Smithfield Road. He charged three pence per night for an adult and one penny for a child. By 1834 he was paying poor rate on the property as an occupier, on the basis of a presumed rental value of £1 15s per year. This value was downgraded for subsequent years to less than half this sum, namely 13s 4d.

This level of rent value does not suggest that the Fieldstaffs offered a high standard of accommodation. Lodgers from 1841 onwards were occasionally listed as women of independent means, but this might have been disingenuous or even sardonic as most of the occupants of the house were labourers, or even beggars. At the time of the 1861 census, George and Maria were playing host to their grand-daughter Mary Ann Fieldhouse (who should properly have been identified as Mary Ann Hughes), but also housed eleven boarders aged from their teens to the seventies, born nearby (Ashborne) or much further away (Ireland).

Fieldhouse’s eldest daughter Elizabeth decamped to Burton on Trent with brazier Thomas Hughes and although they probably did not marry, they had numerous children together. They may have been itinerant workers themselves for a time, as the birthplaces of the children are given variously as Ashby in Leicestershire, Stafford, Rugby, and Cheadle as well as Burton. Maria ‘Fieldstaff’ baptised 1839 was probably the oldest illegitimate daughter of Elizabeth and Thomas (rather than the youngest daughter of George and Maria), because when she married she gave her father’s name as Thomas ‘Ewers’, a brazier (thereby claiming mother’s common-law husband as her father for the purposes of marriage registration).

George Fieldstaff was buried at St Mary’s church in Uttoxeter apparently aged 75, and left no will. His only known descendants arise from the union of his daughter Elizabeth with Thomas Hughes, and who took the surname Fieldstaff-Hughes.

Sources: Staffordshire Record Office Q/SB 1829 M/20a; D3891/6/34/2/32 overseers’ voucher 1829; D3891/6/34/6/27; D3891/6/35/2/29 overseers’ voucher 1830; D3891/6/38/3/6 overseers’ voucher 1832; D3891/6/39/8/52a overseers’ voucher 1833; D3891/6/70-75 Uttoxeter poor rate books 1832-1838; 1841, 1851 and 1861 censuses; baptisms of 9 November 1796, 27 March 1821, 11 December 1823, 13 May 1835, 30 August 1839, Uttoxeter, and 1860 Roman Catholic church, Burton on Trent; marriages of 2 November 1820, Milwich, 17 January 1825, Uttoxeter, and 1863, Burton on Trent; burials of 30 August 1824 and 23 August 1864, Uttoxeter; http://www.rootschat.com/forum/index.php?topic=500878.msg3577237#msg3577237; with thanks to Dave Marriott for information about Smithy Lane/Smithfield Road.