If it takes a village to raise a child, did it also take a Village to run a workhouse? This is clearly a rather clumsy play on the surname of the Darlaston workhouse governor in the 1820s, but it also raises a more serious question about the tenor of workhouse life.

Thomas Village was allegedly born in Birmingham in 1785 or 1786, but his baptism has not been found. He first emerges in genealogical data in 1810, when he married Ann Osborn (also in Birmingham). Thereafter, and despite their unusual surname, the couple do not resurface once more until their appearance in the Darlaston overseers’ vouchers. It seems possible that they did not have any children, as they were both in their mid-30s at the time of marriage and no relevant baptisms appear in the 1810s.

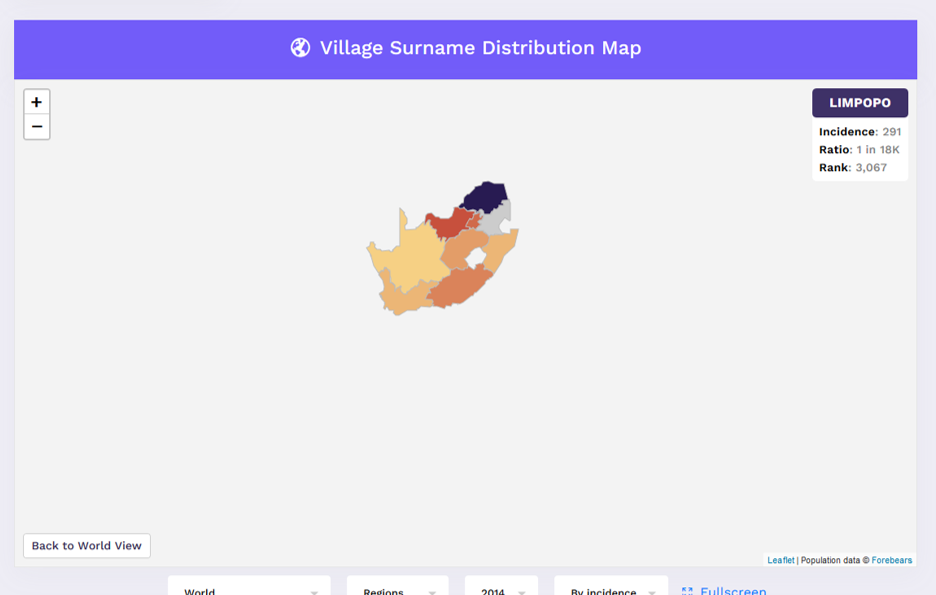

The surname ‘Village’ is now more prevalent in South Africa than in any other country, with a relative concentration of people in Limpopo.

By 1823 the Villages were master and matron of the Darlaston workhouse, catering for between 25 and 30 inmates. Thomas undertook other work on the parish’s behalf, including making journeys on poor-law business and holding sales of goods taken from Darlaston residents in distress, although whether for non-payment of the poor rate is not specified. This suggests that Thomas was also the salaried overseer, also known as assistant or permanent overseer, for Darlaston.

This experience of workhouse management led to future employment for the husband and wife team, while the New Poor Law extended the scale of workhouse management experiences: in 1841 Thomas and Ann Village were the master and matron of the Erdington Union workhouse, in a building formerly used as the Erdington parish workhouse. At that time they were responsible for 123 other residents ranging from those in infancy to one nonagenarian.

They earned enough to retire before the 1851 census, when they were described as a ‘retired plate worker’ and ‘former dressmaker’ respectively. Familiarity with textiles was probably a significant plus for a prospective institutional matron, but it is less clear why a background in metal-working was indicative of success for a master. Ann died in 1862 at the romantic address ‘Shakespeare Cottage’ and Thomas died in 1866. They were both buried in the Warstone Lane Cemetery, Birmingham.

How responsible might Thomas and Ann Village have been for setting the tone of institutional life in their workhouses? Research on autobiographical sources for later in the nineteenth century suggests that staff could be central to establishing an atmosphere of either intimidation or of homeliness. The Erdington Union was known in the later nineteenth century for a rather uncompromising attitude to poor relief, but this does not mean that the Villages pursued harshness as a policy in earlier decades.

There is one shred of evidence for the relationship between the Villages and the resident poor: when Thomas Village died he was worth less than £100 and the sole executrix of his will was one Mary Ann Skelton, spinster of Darlaston. She was not known to be a relative of either Thomas or Ann. Instead, she had been a resident of the Erdington workhouse in 1851 who became the household servant of the couple in their old age and certainly by 1861. Who knew that a former and future pauper might act as executrix for a Governor? Mary Ann Skelton was in the West Bromwich Union workhouse in 1871 and 1881 and probably died in West Bromwich in 1891.

There is no guarantee, of course, that the relationship between the Villages and Skelton was cordial, but the only time she is known to have lived outside a workhouse from 1851 to her death was with them as a servant in 1861, and Thomas trusted her in a legal capacity above (for example) his surviving sisters (Mary Village 1790-1871 and Elizabeth Village 1799-1869) or any nephews and nieces by his other siblings. Whatever social distance was imagined to exist between workhouse staff and their charges was not necessarily strictly observed, and arguably narrowed in later life.

Sources: D1149/6/2/8 Darlaston overseers’ vouchers 1823; 1841, 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881 census; marriage of 5 March 1810; National Probate Calendar; Birmingham Daily Gazette 18 December 1862; www.workhouses.org.uk

Thomas Village is a distant relative of mine. I can offer details about his baptism and details of the property he owned (referred to in the 1861 census). I also have background info about the Erdington Workhouse before it moved to the purpose-built one in Aston in 1860s.

In return I’m intrigued with the Darlaston Overseers vouchers. Where could Ia access these, please?

Kind regards