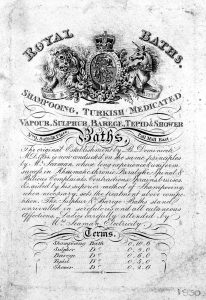

Medicated vapour baths became popular in England in the 1820s. Such things were available in earlier decades, but Sake Deen Mohamed advertised them via both his published works and his bathing establishment at Brighton. The treatment he offered for muscular and similar ailments involved massage and steamy bathing with the addition of Indian oils. He introduced the word ‘shampooing’ to popular usage, although with a slightly different meaning to its current one (ie rubbing the body, whereas we lather our hair). Mohamed was named ‘shampooing surgeon’ to George IV and William IV.

https://wellcomecollection.org/works/xg5ewh67

What did such fashionable treatments have to do with the Staffordshire poor? We might have guessed ‘none’: but we would have been wrong. Spa towns like Buxton had long made bathing facilities available to poor patients, albeit in a heavily regulated way. In 1785 for example the poor were admitted to bathe at Buxton between the months of May and October, on Mondays only, and funded places were limited to sixteen beneficiaries at any one time. Successful applicants to the Buxton charity had to support their appeal with ‘a letter of recommendation from some lady or gentleman from his own locality certifying whether he was a proper object of charity, and if the patient was a pauper, also a certificate signed by the Churchwardens or Overseers of the poor that the pauper’s settlement was in, and a certificate from a physician or apothecary that the case was proper for the Buxton waters’. In the 1820s, though, copyists of Mohamed developed their own vapour bathing equipment which was not dependent on location. Charles Whitlaw patented his medicated baths which could be installed in any town, and published his Scriptural Code of Health in 1838 thanking Anglican and Dissenting clergy for funding treatments for miscellanous workhouse poor.

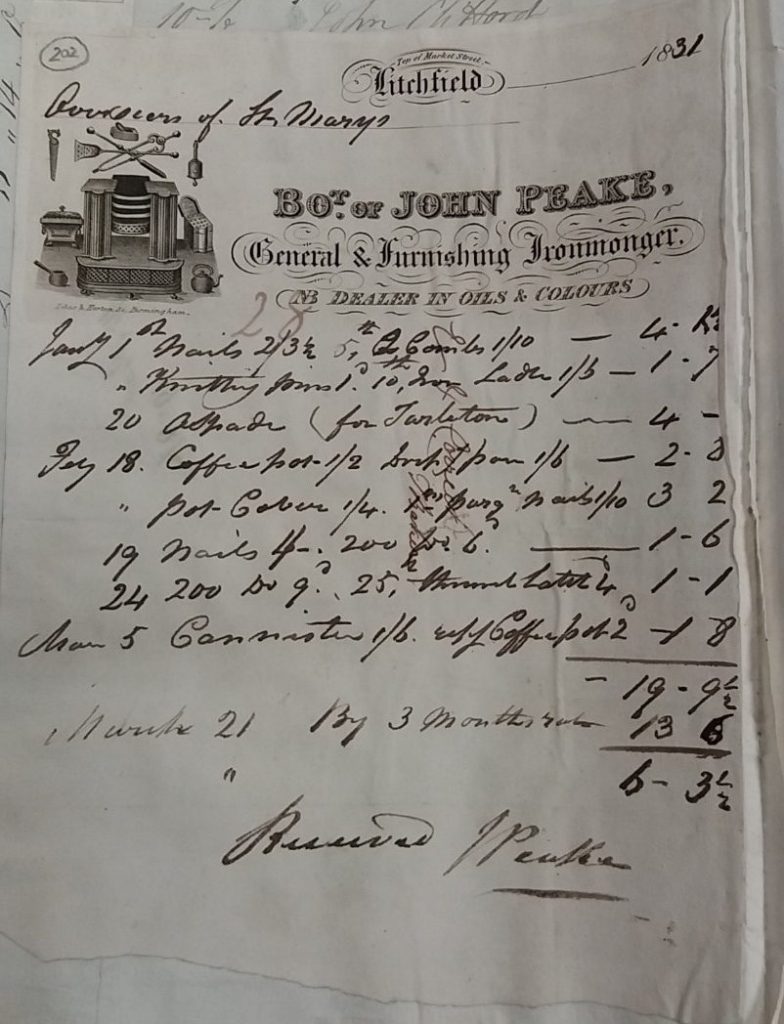

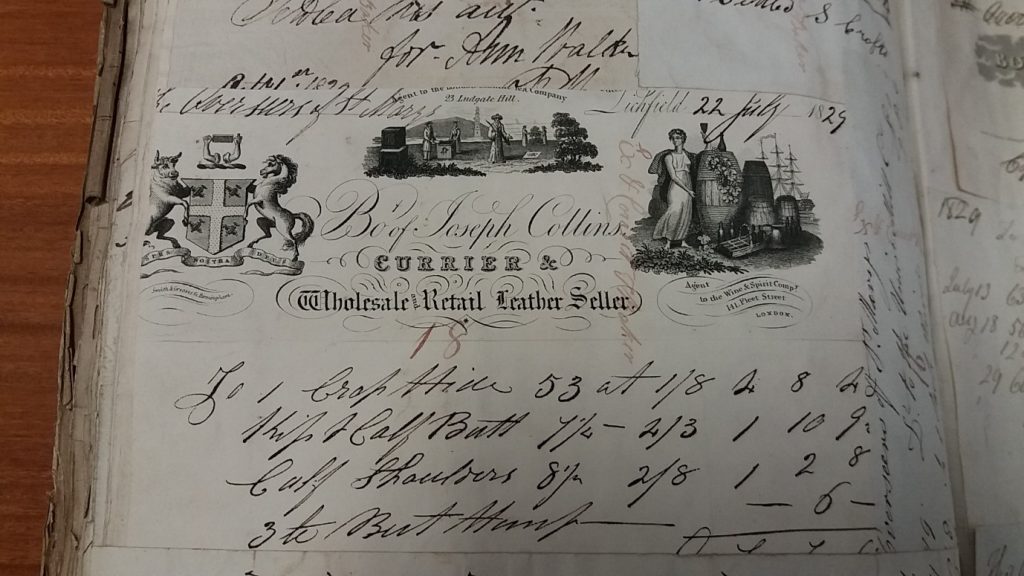

It was still a surprise, though, to discover that the parish of Alrewas actually sent its paupers to a medicated vapour bathing establishment in Wolverhampton. The vouchers show that in 1831 the parish sent William Riley to the baths run by surgeon Edward Hayling Coleman at Dudley Street in Wolverhampton, albeit the parish paid the resulting bill rather slowly. In early 1832 they also sent a woman called Eams, possible Ann Eams born at Fradley in 1805 or her mother Mary, who Coleman reported in March to be ‘somewhat better’ as a result.

Coleman had invested in Whitlaw’s patented bathing equipment, and set up two facilities for treatment. There was a public bath in Dudley Street costing 3s6d a time, and he also saw the more prosperous of his patients at his own house in Salop Street for 5s per bathing session. We do not know the diagnosis for either Riley or Eams, but Coleman promoted his baths for cases of scrofula, cutaneous diseases, liver complaints, gout, rheumatism, asthma and (very optimistically) ‘cancer in it’s incipient stage’. When the first cholera epidemic swept Britain in 1831-2, Coleman even reserved one or more of his baths ‘for the gratuitous use of the poor’.

Sources: Ernest Axon, ‘Historical Notes on Buxton, its Inhabitants and Visitors: Buxton Doctors since 1700’ (1939), among the ‘Axon Papers’ held at Buxton Museum and Art Gallery ; Charles Whitlaw, The Scriptural Code of Health (London, 1838); SRO D 783/2/3/12/8/2/2 Alrewas overseers’ voucher, bill of Edward Coleman to the parish 1831; D 783/2/3/13/7/1 Alrewas overseers’ correspondence, letter from Edward Coleman 1832; Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser 22 June 1831 and 16 November 1831.