Pattens are a type of footwear which must have been worn by many of the women of East Hoathly during the 18th century and well into the 19th. They consisted of a wooden sole with a leather or cloth strap which was tied or fastened over the wearer’s shoes. This wooden sole was mounted on an oval cast-iron ring. They were designed to raise the wearer an inch or so above the ground, providing a platform. So they were very useful during the long winter months, not only protecting shoes but also the long skirts which would otherwise have draped in the mud and dirt (including animal dung).

Pattens were very much in demand by the villagers. They are mentioned regularly within The Diary of Thomas Turner 1754-1765. [1] As both shopkeeper of East Hoathly and Overseer of the Poor, Turner was involved in the whole process, ordering and buying the pattens, then distributing them to the poor as needed. They were included in many of the overseers’ vouchers of 1760s – 1830s, which recorded the various requirements of the poor of East Hoathly. These were meticulous lists and many were headed ‘The Overseers of East Hothly to Thos. Turner’ – thus claiming his expenses and written in his very distinctive handwriting.

According to the entries in the diary, the pattens were usually bought by the half dozen or dozen and cost nine pence per pair. For example, in 1755, a total of 80 pairs were bought by Thomas Turner, and nine transactions are recorded from February to November. They are all from the same supplier, Thomas Freeman, who is noted in Appendix C of the diary [2] as clog and patten-maker of Mayfield. Most were described as ‘women’s cloth pattens’ (indicating the cloth straps), but some were for girls, and orders usually included an equal number of clogs which were cheaper. It would appear that there were enough to supply all the women and girls of East Hoathly, who were then well shod and able to cope with the muddy roads of the village.

An entry in Turner’s diary records such a purchase along with a typically detailed account of a busy day in 1755:

Thursday, Feb. 20: At home all day. Remarkable cold. Mr Jordan dined with me. Paid the post boy for Thomas Freeman 6s. (to wit) for 6 pairs girl’s pattens and 6 pairs clogs. Charles Diggens brought my coat. I paid him 9s. 5d. (to wit) for altering a pair of breeches and mending a greatcoat 9d.; for making 2 pairs spatterdashes 1s. 2d.; for making a coat 7s. 6d. John Watford Jr. a-fetching dung from the stable for me today; agreed to give him 18d. Paid for bread 1d. [3]

And then in September a larger order anticipating the autumn weather and worse to come:

Friday, Sept. 19: At home all day. Bleeded in the morning. Paid for 12 prs pattens and 13 prs clogs (rec’d this day from Thomas Freeman of Mayfield by his servant) 14s. 5d. [4]

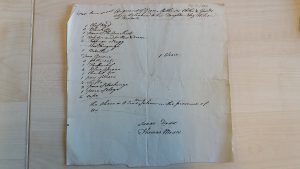

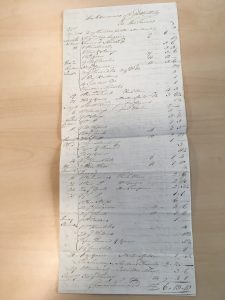

In 1790 Turner compiled and submitted a voucher, headed ‘The Overseers of East Hothly To Tho Turner’ [5]. This covers the year from April to the following March (reflecting the tax year, then as now) and is three pages long with 136 items listed. It provides us with a good idea of the clothing needs of the village poor, and also of their dressmaking activities. For example, Fanny Stevens receives items on six occasions. 25th May, Turner records that she received various fabrics and sewing items and also a pair of pattens, which cost one shilling indicating Turner’s profit:

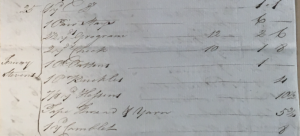

1 yd Do [Check], 1 Pair Stays, 21/2 yd. Grogram, 2 yd. Check, 1 Pr. Pattens, 1 Pr. Buckles, 1/8 yd Hessens, Tape Thread & Yarn, 1 yd. Camblet.

Pattens had certain disadvantages. They must have been quite precarious to walk in. Although from Turner’s records it appears that a smaller size was available for girls so they would have had years of practice. They were known to be noisy and were described as making a ‘clinking’ sound. Jane Austen wrote in ‘Persuasion’ of the ‘ceaseless clink of pattens’, referring to life in Bath. [6] Of course in a country village such as East Hoathly in the 1700s there were no pavements and maybe not even cobbles. However the ‘clinking’ in church would probably have been frowned upon.

Pattens were worn by all sections of society at this time. The wealthier classes had a fashionable version of the humble patten which matched their outfits, made of silks and satins. They were not designed for walking through muddy streets, but probably just from carriage to front door.

The Worshipful Company of Pattenmakers is a City of London Livery Company which was awarded its Royal Charter in 1670. It still exists today as a charitable foundation, funding the making of bespoke orthopaedic shoes for injured servicemen.

- Thomas Turner, The Diary of Thomas Turner, 1754-1765, ed. David Vaisey, 1984.

- Turner, 346

- Turner transcription

- Ibid

- East Hoathly Overseer’s Voucher: ESRO PAR378/31/3/22/12/31-39

- Jane Austen, Persuasion, 1817

written by Christine Morris