Poorhouses were not only in need of supplies but also maintenance. William Coulston was one of the traders helping to keep Kirkby Lonsdale poorhouse running.

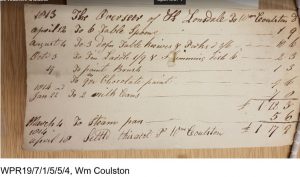

Coulston’s business was situated in the old Market Square of Kirkby Lonsdale, well-positioned to take advantage of trading opportunities. He supplied the poorhouse with various cutlery items, milk cans ‘chocolate’ paint and a brush. His receipted bills totalled 14s in August 1811 and £1 17s 9d in April 1814. [1]

Presumably this paint was destined for use outside owing to its durable properties. The British manufactory Company of London supplied different colours of paint, expounding their cheapness, durability and readiness to be thinned with prepared oils. [2]

Around this time other bills were sent to Thomas Parkinson who was the governor of the poorhouse, which was built in 1811 for the use of the townships of Kirkby Lonsdale.[3]

William Coulston was baptised 16 July 1766 in Kirkby Londsdale, as were his siblings . His older brother Thomas (baptised 29 October 1758) was also a glazier while his sister Margaret (baptised 14 June 1761) married a soldier, John Dunn in 1782. [4] Coulston married Sarah Baines on 1 December 1798 in Kirkby Lonsdale where all their children were born. William, born in 1798, didn’t survive long. Another son also named William and daughter Margaret followed in 1801 and 1802. In 1804 when Elizabeth was born Christopher Ellershaw began his apprenticehip as a tinplate worker with Coulston.[5] The Coulstons had another two daughters Sarah (b.1805) and Jane (b.1807). Tragedy struck the family in 1817 when only son William, aged sixteen, drowned while swimming in the River Lune. [6]

Coulston appears to have continued in business for a number of years appearing in the 1829 trade directory. [7] He died 10 May 1835 around the time the poorhouse was closed. [8]

Thomas Parkinson had been the Governor of the poorhouse until its closure. Parkinson and his wife Mary Gill were then employed as master and mistress of the workhouse East Ward, Kirkby Stephen, in 1836 remaining there for the next nine years. [9]

By 1841 William’s widow and her unmarried daughter Margaret were living with daughter Sarah and her husband at Horse Market in the town. Both were of ‘independent means’.[10]. Sarah had married Isaac Dalkin, a currier, on 14 February 1831 in Kirkby Lonsdale. The Coulstons’ youngest daughter, Jane, married John Carter, a tinman, in Liverpool. [11]. When Sarah Coulston the elder died on 21 January 1843 the local newspaper referred to her having been ill for some time. She was buried at Kirkby Lonsdale alongside her husband and son William. [12]

Margaret Coulston perhaps finding herself in reduced circumstances set up in business in the busy area of Mill Brow in the town and can be fond in the trade directories in subsequent years. An Elizabeth Coulston is listed as a tea dealer in the same directory and location as Margaret in 1851 but their relationship is unknown. [13] As Margaret’s sister Elizabeth had married James Atkinson, a saddler, on 20 September 1823 it assumed it is not her. [14]. Margaret continued in business for at least the next 10 years. She died on 9 April 1868.[15]

sources

[1] Cumbria Archives, Kirkby Lonsdale Overseers’ vouchers, WPR19/7/1/5/3/13, 31 August 1811, WPR19/7/1/5/5/4, 4 March 1814

[2] Cumberland Pacquet and Whitehaven Ware’s Advertiser, 7 March 1815

[3] Cumbria Archives, Kirkby Lonsdale Overseers’ voucher, WPR19/7/1/5/3/61/6, 4 November 1811. .www.thepoorlaw.org, Peter Collinge, The Kirkby Lonsdale Digester, 1 June 2020

[4] Lancashire Archives, Marriage Bonds, APR 11, Thomas Coulston, glazier and Sarah Hudson, 18 November 1780, John Dunn, soldier, and Margaret Coulston, 15 April 1782

[5] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Collection: Board of Stamps: Apprenticeship Books: Series IR 1; Class: IR 1; Piece: 71, UK Register of Duties Paid for Apprenticeship Indentures,1710-1811 [accessed at www.ancestry.co.uk]

[6] Lancaster Gazette, 28 June 1817, p. 3, col. d.

[7 ] Principal Inhabitants of Cumberland and Westmorland 1829, Parson and White’s Directory compiled by R Gregg

[8] Kendal Mercury, 16 May 1835, p. 3, col. e

[9] Kendal Mercury 21 December 1850, p. 3, col. g

[10] TNA, 1841 Census HO107; Piece: 1161; Book: 9; Civil Parish: Kirkby Lonsdale; County: Westmorland; Enumeration District: 15; Folio: 39; Page: 15; Line: 18; GSU roll: 464191

[11] Lancaster Gazette 13 April 1833 p2 col e

[12] Kendal Mercury, 28 January 1843 p3 col f www.findagrave.org

[13] Mannex and Co., History & Directory and Topography of Westmorland (1851) [accessed at www.ancestry.co.uk]

[14] Lancashire Archives, Marriage Bonds, APR 11, Elizabeth Coulston, James Atkinson, saddler, 19 September 1823

[15] Kendal Mercury, 25 April 1868, p. 3, col. g

William Coulston’s will, plumber and glazier, is held at Lancashire Archives, WRW/L/R640, 29 August 1835