Researched and written by Margaret Dean.

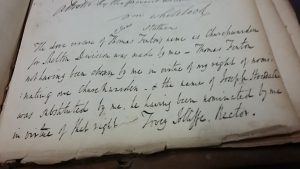

In 1833-34 John Tordiff’s name appears on a Church Warden’s bill for the Parish of Wigton for the supply of wine at a cost of £1.10.0. The bill was settled by Henry Hoodless, Stationer, Wigton. On the reverse side of Tordiff’s bill is a second bill for registers from Mr Hoodless for £5.10.0. It is from this side of the bill that the date is assumed.

The surname Tordiff is quite common in the Wigton, Holme Cultrum, and West Cumberland area, therefore, John Tordiff’s movements prior to this bill and business as Spirit Merchant in Market Street, Wigton, cannot currently be discerned with certainty.

On 29 August 1833 Tordiff married Mary Russell (b. 20 May 1808) in Whitehaven. Her father, John Russell, worked as a maltster. Shortly after the marriage Tordiff took over the grocery premises of John Meals in the Market Place, Wigton. John Meals’ name also appears on the same bill for the supply of wine (and on sveral other vouchers). Meals eventually retired to Cockermouth with his wife Mary (née Brown). In the 1851 Census the Meals were living in Castle Street. Meals died in 1857. Prior to this, Meals had placed a notice in the newspaper stating that he had relinquished his business and informing the public that John Tordiff had taken over his stock. In the practice of the time, Meals hoped that the public would favour Tordiff with its business.

In the Carlisle Journal there is further evidence of Tordiff in Wigton; an advert for the sale of a freehold estate at Hayton. The property was being sold at the Sun Inn, the house of John Cloag, innkeeper, Aspatria on 31 July 1834: ‘Particulars may be known on application to John Tordiff of Wigton Spirit Marchant’. Tordiff had also been acting as umpire in a horse race involving a wager between John Kidd, a Mr Pattinson, Mr William Buttery (erstwhile assistant overseer of Wigton) and a Mr Simpson.

By August 1834 John and Mary Tordiff had a son, John Russell Tordiff and all appeared to be going well. By December 1836, however, Tordiff’s fortunes were changing. His business ceased trading. In effect he has been declared bankrupt and those appointed to settle his estate were charged with the task of calling in the money owed to him so that they can pay his creditors. In February 1837 a dividend of 10s was paid out to creditors by the assignees at John Hewson’s office. Tordiff’s business was taken over by Daniel Harrison.

After this episode, John and Mary Tordiff went to Liverpool, where a daughter Hannah Elizabeth was born in 1838. There is no information as to his circumstances or if he was in business. He would only have been allowed to start a new business, however, once a certificate of discharge from his bankruptcy had been declared. All did not go well.

On May 5 1839 an inquest was held at The Grapes, Church Row, Aldgate London on John Tordiff, aged 35. The suggestion is that he may have taken his own life as two phials of laudanum (a preparation of alcohol containing the opium derivative morphine), were found with his body. He had been living for a month at the Three Colts, Old Ford, and was employed by Messrs Chapman, distillers. It is here that Tordiff’s wife had sold some stock from the funds at a disadvantage. A nurse who gave evidence said Tordiff had been in the London Hospital and had told her he had taken laudanum before. Bell’s Weekly Messenger reported his death as a ‘Determined case of poisoning of a decayed merchant’, stating that he had formally been in a very extensive way of business. Examination of his body showed he had led a dissipated life. It would seem that John Tordiff died by his own hand either by accident or on purpose. He was buried at St Botolph Without, Aldgate, London May 1839.

John Tordiff’s wife Mary, aged 30, went to Aspatria with their children John Russell and Hannah Elizabeth aged six and two respectively. She took up work as a schoolmistress. On 26 July 1845 she married spirit dealer Robert Graham (b.1821 in Distington, Cumberland) and had two further children: Mary Jane (b.1847) and Dorothy (b.1851). They can be found at Scotland Road, Liverpool, on the 1851 Census along with her and John Tordiff’s children John and Hannah. In 1861 Mary was widowed again but carried on Graham’s business as a victualler.

Death notices in Gore’s Liverpool General Advertiser 4 April 1867 and the Liverpool Mercury 2 April 1857 reported the death of an Elizabeth Tordiff age 81 at 36 Lodge Lane. For 40 years she had been the landlady of the Rams Head, Workington and latterly nurse at the Deaf and Dumb Institute, Oxford Street, Liverpool. According to the 1841 Census Elizabeth was living in Toxteth, Liverpool, and then at the above Institute in 1861 as a widow and Sick Nurse. It is possible that this is John Tordiff’s mother.

Hannah Elizabeth Tordiff (1838–1906) married William Wilson (a pilot mariner then dock worker) in Liverpool on 7 December 1861 and had five children: Alex Poole, Dorah, William R., Harold W. and Isabella.

John Russell Tordiff (1834–1871) was in business with a Benjamin Lambert prior to the dissolution of the business in1868. He also was a book keeper dealing with accounts, and lived with his sister’s family prior to his death on 9 May 1871. His death announcement in the Carlisle Patriot 19 May 1871 states he is the son of John Tordiff late Spirit Merchant of Wigton.

Sources

Cumbria Archives, PR36/V/21/4, Wigton Overseers’ Vouchers, 1833–34

Ancestry.co.uk, England Select Marriages 1538–1973

britishnewspaperarchivesonline.co.uk

Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 5 May 1839

Carlisle Patriot, 23 November 1833, 16 April 1836, 28 March 1857, 19 May 1871

Carlisle Journal, 14 June 1834, 5 July 1834, 18 July 1834, 31 December 1836, 4 March 1837

The Chartist, 5 May 1839

Gore’s Liverpool General Advertiser, 4 April 1867

Liverpool Mail 7, December 1861

Liverpool Mercury, 2 April 1867

Liverpool Daily Post, 13 May 1871

This is a work in progress, subject to change as new research is conducted.