Although baptised in Swinton, Berwickshire, Alexander Cockburn and his brother John (1781-1835) were to establish themselves in business in Carlisle. John may have arrived first, with Alexander joining him later. Marrying Mary Storey, the daughter of Johnathan Storey, a spirit merchant in Shaddongate Parish, the register describes Alexander as a pipe maker in 1817.[1] The Cockburn brothers also had a small premises in Fisher Street where they also sold tobacco. [2]

Clay for the pipes was available locally. The Pipery was situated near the Mill Race in Shaddongate.[3] Once a small suburb of Carlisle, it was on the road to Dalston just outside the city walls. At the end of the eighteenth century Shaddongate saw an influx of migrant workers looking for employment opportunities in the manufacturing industries. Many of these workers were of Irish and Scots origin.

Alexander and Mary’s daughter Margaret was baptised 28 February 1819 [4] by which time Alexander also had a Grocer’s shop at Annetwell Street within the area of the old city. Shortly after this in 1823 the canal was opened improvng trading links especially to Liverpool. It was here that another brother James (1801-1868) moved. Initially a flour miller, he married his first wife Ann Storey (1805-1852), [5] the sister of Mary Storey in 1824. While the brothers’ sister Mary Anne Hepburn (1797) married Steven Somerville and lived in Edinburgh, other siblings were Alison (1783-1811), Robert (b.1786), Margaret (b. 1789), Agnes (b.1791), and Isobel (b.1801). [6] Their parents being Alexander Cockburn (1752-1825 ), a fewer or blacksmith, and Margaret Service (1757-1829). [7]

Alexander and Mary don’t appear to have had any more children, before Mary died in childbirth on 22 November 1824 aged 29 at Annetwell Street. [8]

The brothers continued with their Pipery in Shaddongate despite the unrest that had developed in the area. Living conditions were poor, overcrowding common for many. The migrants being unfairly blamed for some of the trouble. John, Alexander’s brother gave evidence at the subsequent investigation into the resulting deaths in the Shaddongate riots of 1826. After the Riots’ of 1826, the Cumberland Pacquet and Whitehaven Ware’s Advertiser described the arrival of Benjamin Batty to direct efforts to restore order in the area. He was to instigate the formation of a police force to combat insubordination in the suburb. His first attempt to restore order in February 1827 led to him having to take refuge in Mr Storey’s house after being set upon. It is possible this could have been Mary Story’s father’s abode.[9]

24 January 1831 Alexander married again. His wife Jane Ross (1793-1873). [10] was the widow of Hugh Ross and the daughter of John Tallentire and Jane Henderson. A son, John Tallentire, was born 21 December 1834.[11]

For a brief time John Cockburn, after trading as a haberdasher and paper dealer, became a bookseller at 34 Scotch Street, once occupied by Mr Jollie the publisher. At the time, Alexander was listed at Irish Gate Brow [Annetwell Street].[12]

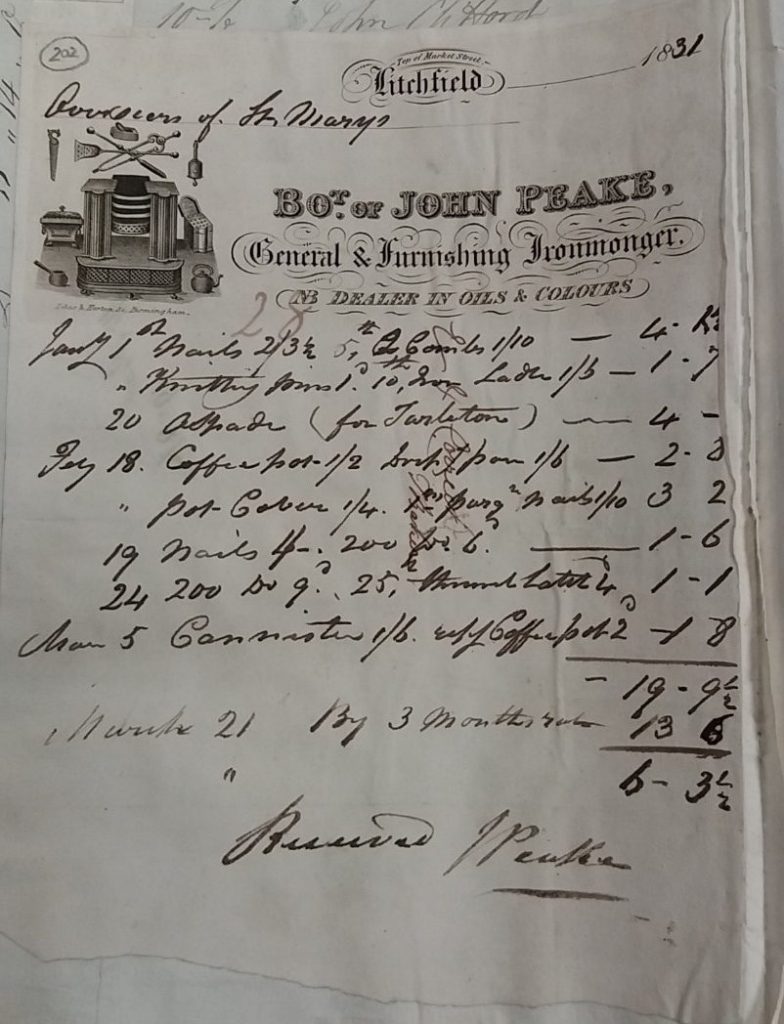

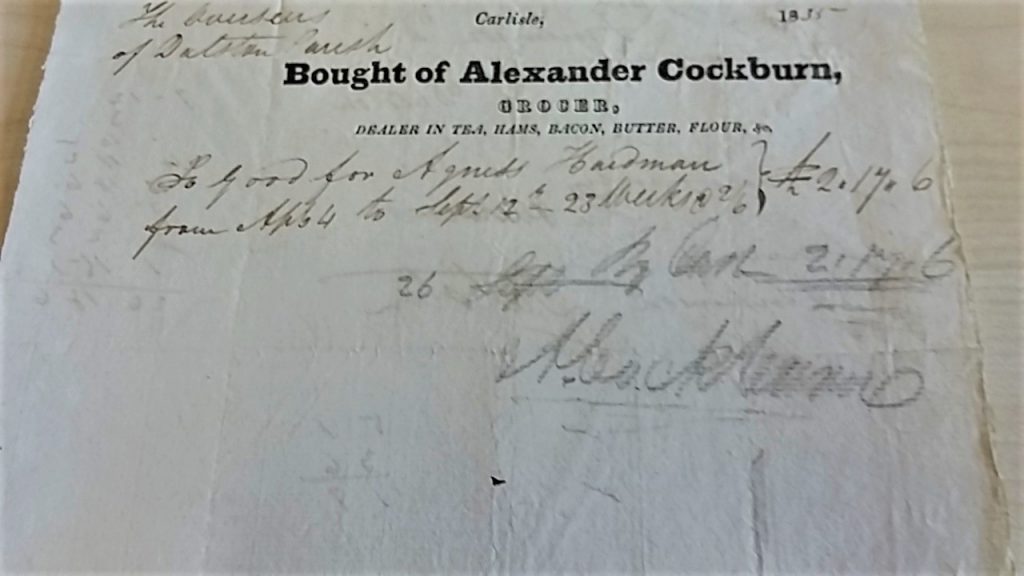

On Alexander Cockburn’s headed bill of September 1835 to Dalston’s Overseers he is described as a grocer supplying goods to Agness Ha[e]rdman for 23 weeks at a cost of £2.17s. 6d. [13] Agnes’s life is a mystery.

Well established in Carlisle, Alexander was elected a Counsellor. [14] All appeared to be going well. He owned three farms which he let. [15] Then on 16 September 1835 brother John died aged 54 [16] and on 3 January 1837 a fiat of bankruptcy was issued against Alexander. [17] The fact being made well known by various newspapers. The Cumberland and Westmorland and Whitehaven Ware’s Advertiser further reiterated his status ‘Peter Dixon was elected to Alderman of the Corporation of Carlisle on Tuesday in the rooms of A Cockburn a bankrupt’.[18] He relinquished the office of Alderman on 9 November 1836, [19] and his farm properties were advertised for sale. [20] Creditors were asked to make it known what they were owed. The Pipery in Shaddongate was advertised for lease, by the now owner Mrs Armstong in May 1838. [21] A Certificate was issued in April 1837 [22] which would effectively discharge him of what was asked of him under the bankruptcy proceedings, while final dividends were paid out in 1838. [23]

Denton Corn Mill was offered for lease by Mrs Dixon [24] and Alexander was successful in taking over the Mill. He placed a notice in the Carlisle Journal of 1838 as follows:-

A Cockburn having entered on this commodious mill respectfully informs the public that the arrangements which he has made enable him to execute all orders in this line with the greatest care and expedition’. [25]

Alexander Cockburn was not re-elected Councillor in November 1841 at the Municipal Elections for Caldewgate Ward.[26] The next year, on 21 May 1842 Alexander died aged 48. [27] His death appeared in the Liverpool Standard and Commercial Advertiser on 27 May, where brother James was living at Aigburth, Toll Gate near Liverpool.[28] The obituary emphasised his role for Carlisle Corporation. Alexander was buried at Holy Trinity Church where his brother John had also been buried, in close proximity to where they had been in business together.

His wife and son didn’t stay on at Denton Mill. [29] They lived in Stanwix Village for a while, as did daughter Margaret who later married William Roxburgh (an estate agent from Liverpool who at one time lodged with them).[30] James Cockburn died in the Workhouse Liverpool 1868 where he appears to have sought surgical treatment. Jane Cockburn died 18 April 1873 aged 80, [31] but before her will could be enacted, her son John Tallentire died 24 April 1873 aged 38 intestate. By then, John Tallentire was a fairly successful building contractor of Bolton Place, Carlisle. As he had no close relatives, the estate went to John Alexander Cockburn (son of Alexander Cockburn’s brother John) of Allenwood Paper Mill.[32]

Sources

[1] Carlisle Patriot, 26 April 1817, p,3. col. e.

[2] Pigot & Co., National and Commercial Directory Cumberland Westmorland and Lancashire for 1828-29 (London and Manchester, J Pigot & Co., 1828).

[3] Carlisle Journal, 2 March 1844, p.4, col. b.

[4] Cumbria Archives, PR/47 25, St Mary’s Parish, Carlisle, Baptism Register 1813-1822

[5] Liverpool, England Church of England Marriages and Banns 1754-1935 [accessed at www.ancestry.co.uk, 6 June 2020]

[6] Berwickshire Swinton and Simprim Church of Scotland Birth serach [accessed at www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk 6 June 2020]

[7]Alexander Cockburn and Margaret Service gravestone at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/125134655

[8]Carlisle Patriot, 27 November 1824 p,3. col,e

[9] Ware’s Cumberland Pacquet and Whitehaven Advertiser, 13 February 1827 p,3. col,e Carlisle Patriot 10 June 1826 p 2-3

[10] Cumbria Archives, PR/47 14, St Mary’s Parish Carlisle Marriage Register 1825-1837

[11] Cumbria Archives, PR/47 27, St Mary’s Parish, Carlisle, Baptism Register 1830- 1853

[12] J. Pigot, National Commercial Directory of Cumberland and Westmorland (London and Manchester: J Pigot & Co., 1834 [accessed at www.ancestry.co.uk p. 23]; Carlisle Journal 9 August 1834

[13] Cumbria Archives, SPC44/2/48/159 Dalston Overseers’ Voucher, September 1835, Alexander Cockburn Grocer , dealer in Tea, Hams, Bacon Butter Flour &c

[14] Carlisle Patriot, 26 December 1835 p,3. col,e

[15] Carlisle Journal, 15 August 1835 p,2 col,e

[16] Carlisle Journal ,19 September 1835 p,3 col,f

[17] Carlisle Journal, 7 January 1837 p,2. col,c

[18] Ware’s Cumberland and Westmorland and Whitehaven Advertiser ,24 January 1837, p,2. col,d

[19] Carlisle Journal, 21 January 1837 p,3. col.b

[20] Carlisle Journal, 29 July 1837 p1 col,e

[21] Carlisle Journal, 12 May 1838 p,2 col,d

[22] Perry’s Bankruptcy Gazette, 8 April 1837, p,6

[23] Carlisle Journal, 15 September 1838 p,1 col,a

[24] Carlisle Journal, 30 December 1837 p,2 col,f

[25] Carlisle Journal ,17 February 1838 p,1 col b

[26] Carlisle Journal, 6 November 1841 p,3 col,6

[27] Carlisle Journal, 21 May 1842 p.3 col f

[28] Liverpool Standard and Commercial Advertiser, 27 May 1842 p,8 col g

[29] Carlisle Journal, 28 May 1842 p,1 col,c

[30] Carlisle Patriot, 30 July 1847 p, 2 col,h

[31] Cumbria Archives, PROB/1873/W346A269, Will of Jane Cockburn

[32]Cumbria Archives , PROB/1873/96, Administration John Tallentire Cockburn 9 May 1873

This is a work in progress subject to change with new research

footnote

Margaret Cockburn [Roxburgh] died 15 January 1848 at her Stepmothers home in Carlisle Carlisle Journal 21 Jan 1848

James Cockburn 2nd wife was Jane Pickering (Graham) married Liverpool 11 February 1855