Who doesn’t like a brand-new note book? As a life-long stationery addict, archives have always appealed to me on two levels, namely the content of the documents and the materiality of the paper. Therefore, this short post is dedicated to the joy of discovering a new sort of papery artefact among Staffordshire’s poor-law collection, namely the early-nineteenth-century exercise book.

Children, householders, tradesmen and servants may all have found a use for ephemeral paper products enabling them to record lessons, temporary accounts or memoranda, but the key to their general absence from the archive lies in their disposability: why keep one’s earliest spelling book, or rough accounts from past years? We (or perhaps just I?) have been fortunate in the unaccustomed durability of parish accounts which were kept at first in case of queries by magistrates and then later as a consequence of administrative inertia, which for some places resisted drives to clear the parish chest (or respond to paper drives) decades or centuries later.

The parish of Gnosall in Staffordshire was periodically keen to separate different types of overseers’ account in the 1810s, retaining cheap exercise books for different purposes. Sometimes these related to discrete parish ‘quarters’ such as Moreton or Cowley, and sometimes the books were kept for types of benefit supplied to the poor (such as clothing). These slim volumes feature a variety of cover illustrations, some of which seem merely decorative and others which are more edgy or unexpected.

The two books above show uncontroversial images of swans on water, or a cameo of two infants titled ‘Autumn’. The cameo is credited in tiny writing to J. Evans of 42 Long Lane (a printer of ballads and engravings in West Smithfield, London) in 1798. The booklets were both clearly workaday tools for the overseers, being covered with calculations and jottings.

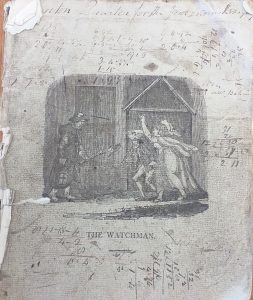

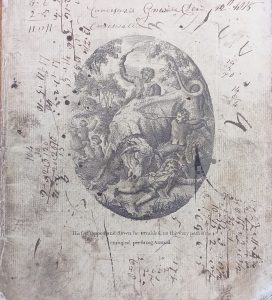

These second two jotting books are similarly graffitied, yet illustrated with images of jeopardy. One shows a night watchman armed with lamp and cudgel confronted by a warring couple: the woman has just knocked off the hat of the man in front of her and the hat is in flight, making this a split-second image. The other booklet also captures a single moment in time, and carries the caption “His foot slipped and down he tumbled, in the very path of the enraged, pursing animal” (which is not obviously a quotation from a well-known text). A small boy is lying at the mercy of a bull, which is being attacked by two other boys carrying respectively a pitchfork and club. A barking dog watches from the side, and other children are seen running from the bull which has evidently broken the restraining rope around it’s neck.

What these pictures have in common is their probable location and chronology, since they all seem redolent of contemporary England in the period 1790 to 1820, chiefly in terms of the countryside but with one apparently urban setting. Purchasers seemingly had a taste for the sweet and tranquil, but also for the amusing or highly-charged scene.

Sources: Staffordshire Record Office D951/5/24, Gnosall parish overseers’ notebook of 1814-15; D951/5/26, Gnosall parish overseers’ notebook of 1817-18; D951/5/27, Gnosall parish overseers’ notebook of 1814-15; D951/5/30, Gnosall parish overseers’ notebook of 1812 onwards.