In the 19th century, the fear of a pauper’s funeral, as expressed in the poem The Pauper’s Drive, was real, and prompted the setting up of burial clubs and specialist insurance policies. In 18th and early 19th century East Hoathly, by contrast, overseers’ accounts and vouchers suggest that the poor could expect a certain level of dignity in their passing-on at the expense of the parish ratepayers.

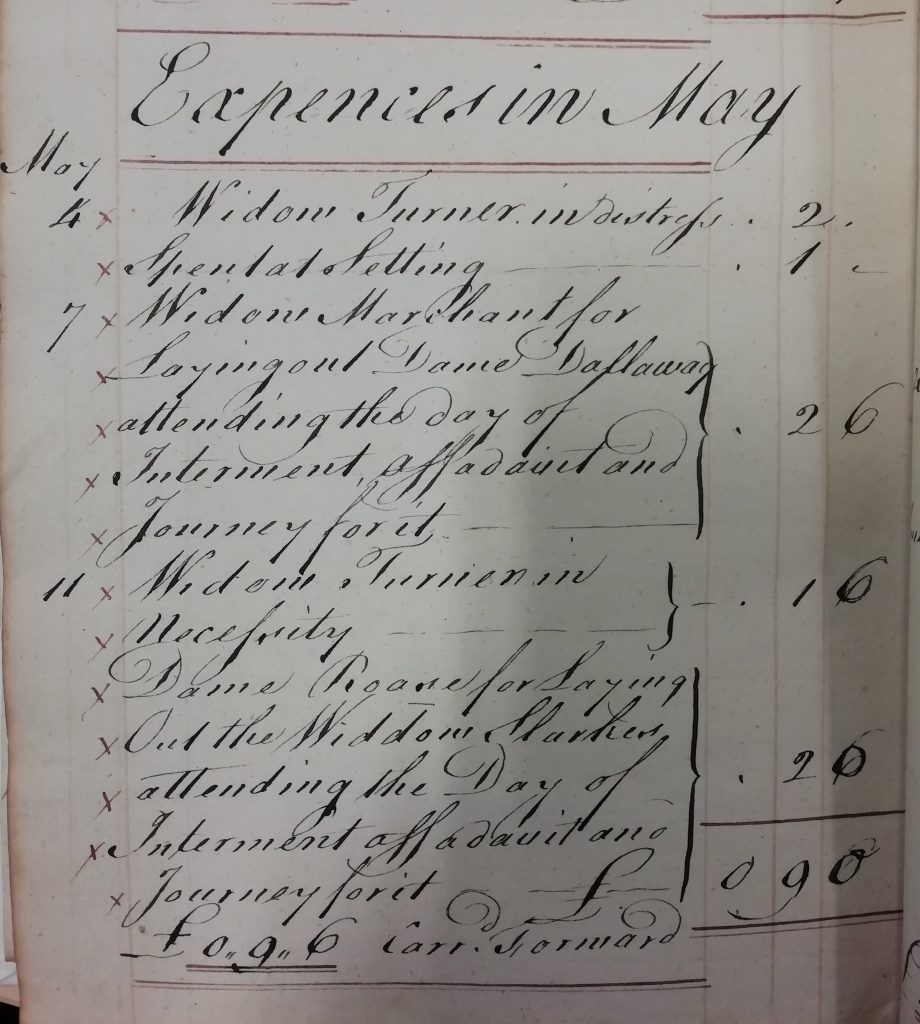

Care began with laying out the body, often, though not exclusively, by women. Widow Slarkes performed the laying out of John Streeter in July 1777 and received the same attention from Dame Roase when she herself died ten months later. The usual payment was 2s 6d. The examples found of laying out all relate to adults suggesting that, unlike most children, they did not have relatives to perform this service for them. In the 18th century, the same women were often also paid to attend on the day of interment and to travel to get an affidavit to prove that the shroud being used was made of woollen. This was a hangover from an Act of 1667 which was aimed at protecting the woollen industry, and which remained on the statute books until 1814, although it was rarely enforced after 1792.

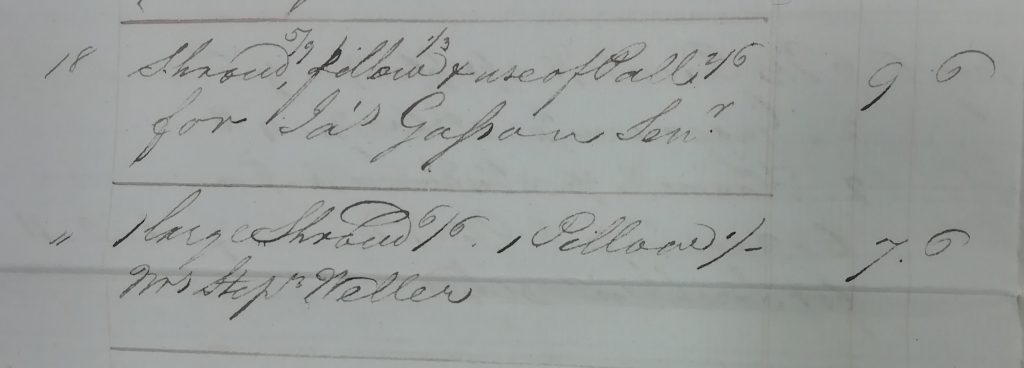

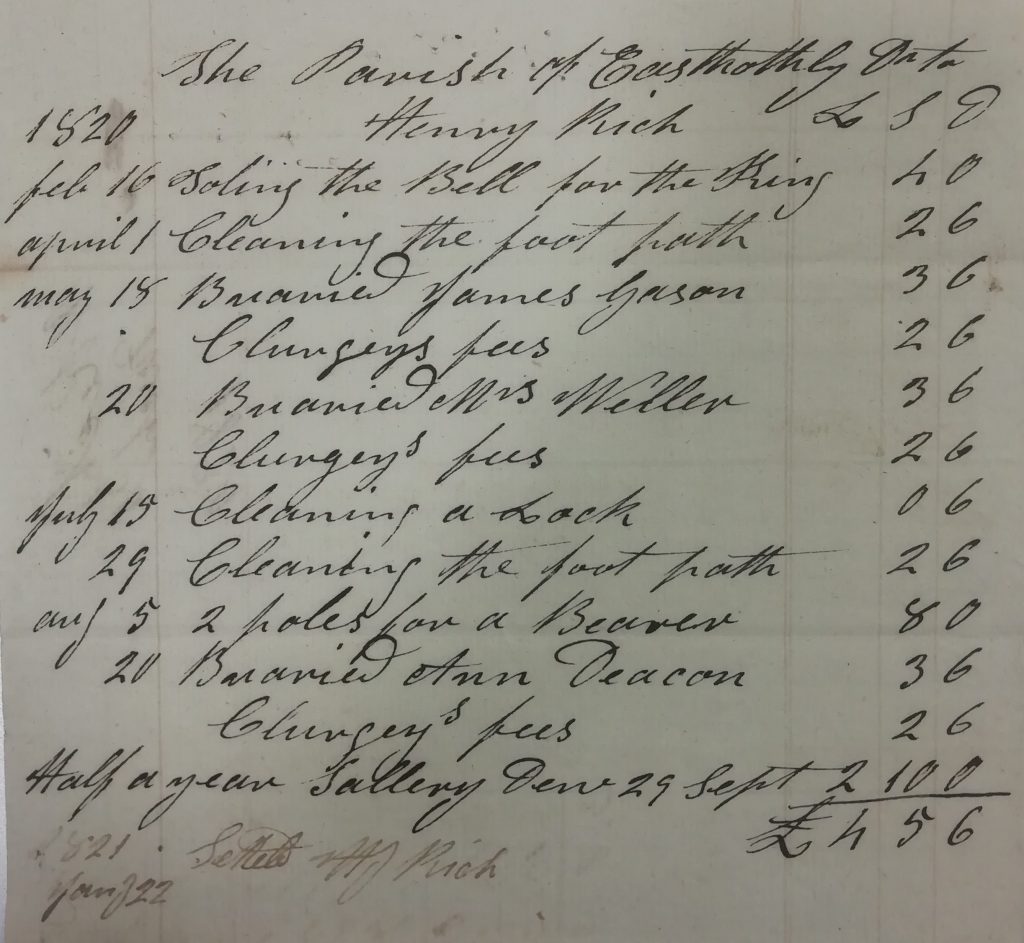

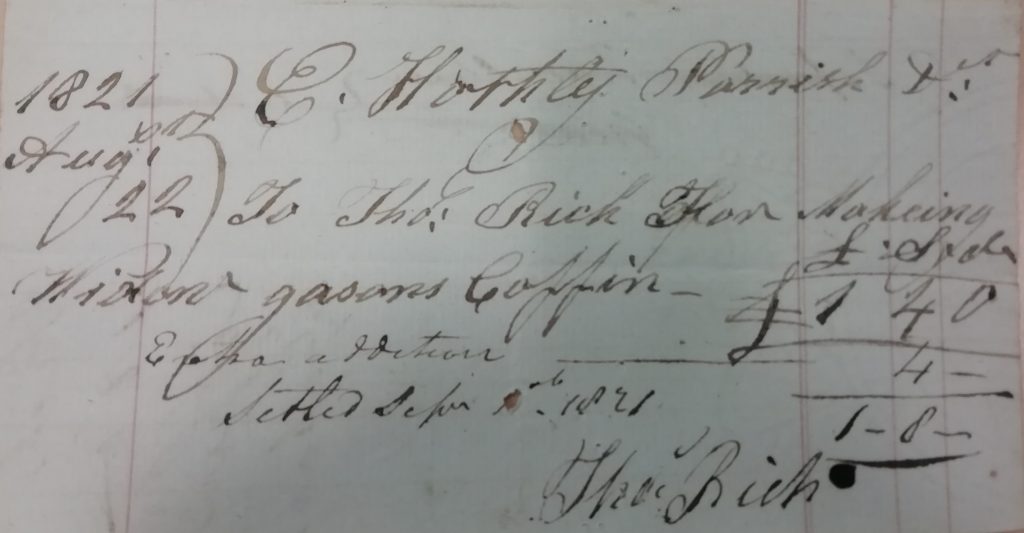

The accounts also mention the supply of shrouds and coffins for funerals of the parish poor. The shroud for Sinden’s child (Ann aged two) cost 2s in 1774 and for Dame Thomas 5s in 1776. By 1821, when the burial in woollen laws no longer applied, the parish was buying calico for shrouds. In 1822 the coffin for Cornford’s child, James, who was buried on 4 March aged 3 weeks, cost 3s, while the adult coffin supplied for James Sinden set the parish back £1 4s 0d. There is little detail about the nature of the coffins, although thy were likely to have been quite basic. There are references to one coffin being ‘plained and oyled’ and to another being made of elm. In the 1820s pillows were provided for the coffin.

Other elements of funerary equipment are also mentioned, although less frequently. A pall – the cloth spread over the coffin – and napkins were supplied in 1781 and palls appear to have been hired in the 19th century at costs between 2s 6d and 5s. There are also occasional references to bearers for carrying the coffin to church and to supplying their poles.

There were also fees to be paid for the funeral ceremony and the accounts show that these too could be covered by the parish. They included the clergyman’s fee for the service – 1s 0d in the late 18th century, 2s 6d by the 1820s – and the clerk’s fees. Although most entries do not detail the individual services for which the clerk was being reimbursed, there are several which suggest that they included digging the grave and tolling the bell.

A case study of Widow (Mary) Gasson, who was buried on 23 August 1821, serves as an example of how the parish intervened at the end of a pauper’s life. Mary was clearly ill in early August as there were payments for her nurse and to Mrs Washer and Widow Susans for attending to her, totalling 8s 6d. After her death, Mrs Washer was paid 2s 6d for laying her out. Philip Turner supplied 6 ½ yards of calico for a shroud costing 4s 4d, and was reimbursed 3s 6d for the use of a pall. Thomas Rich supplied the coffin at a cost of £1 8s 0d. Six bearers received 1s each to carry her to the church, the clerk 3s 6d for the burial and the priest 2s 6d for the service. Finally, beer worth 3s was provided for the funeral, so she did not go to her rest alone and unmourned, and there is plenty of evidence that other pauper funerals were similarly provided for in East Hoathly.

Several pauper inventories survive for East Hoathly together with evidence that the parish officers sold the goods after death. This was certainly the case for Edward Bab/Badcock, who was buried in 1767 ‘upwards of 93 years old’. The parish clearly felt entitled to sell off the goods of paupers to reimburse them for the poor relief that they had paid out even though this wasn’t strictly legal. However, there could also be a kinder story behind this policy – of the parish providing poor relief so that the pauper didn’t have to sell or pawn their goods during their lifetime in order to scrape by and of giving them the dignity of a decent funeral.