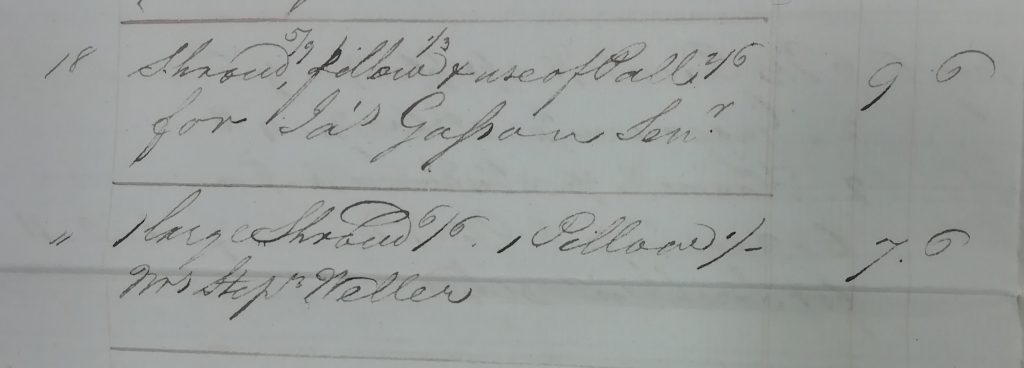

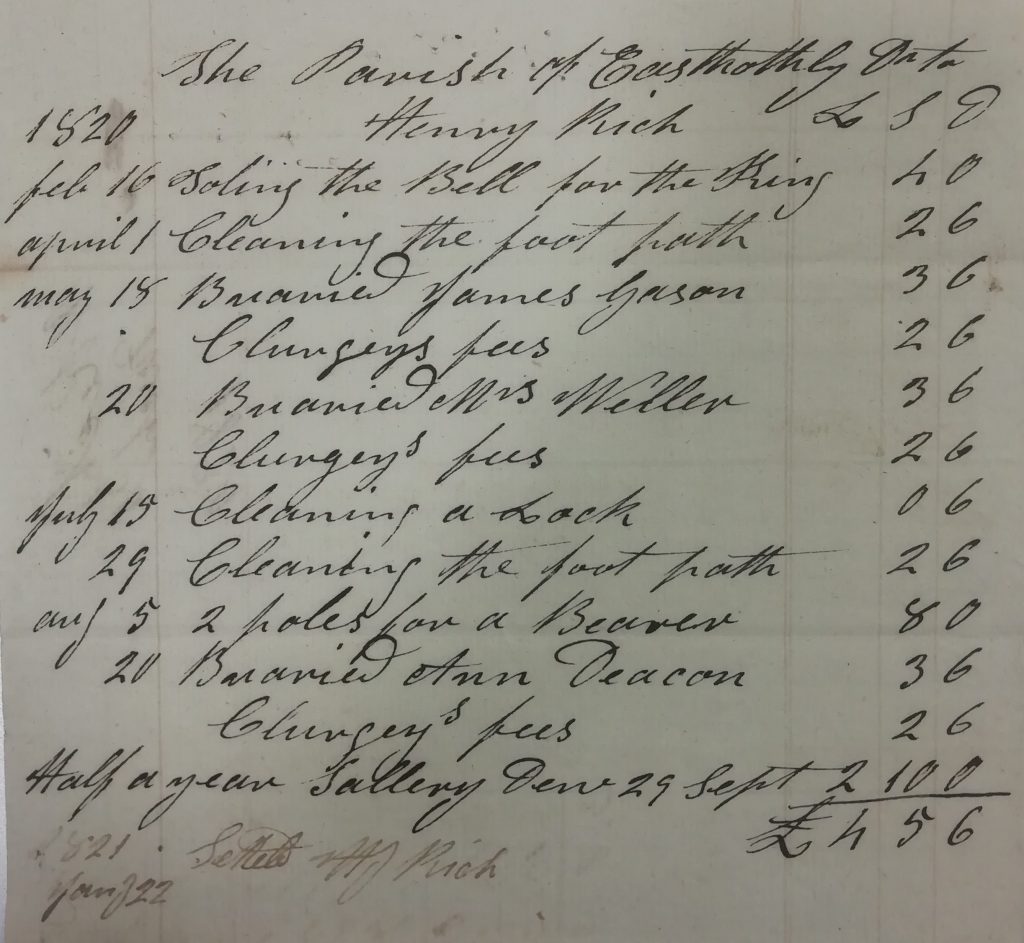

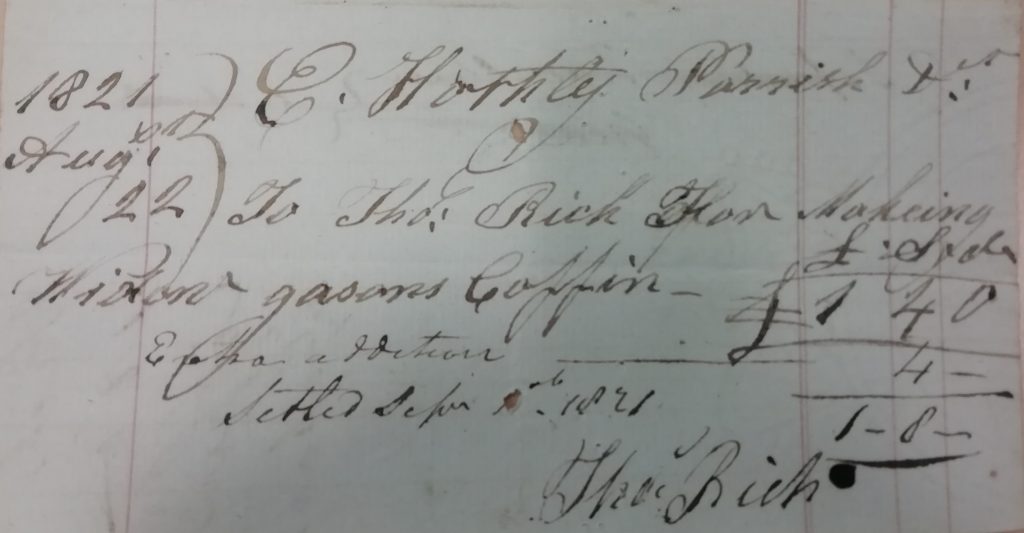

In early 1782 Benjamin Brinkhurst died, leaving a widow and three children. Charles Vine charged the parish 12s 6d for making his coffin on 15th February. John Burgess supplied 4 quarts of beer “for the people at Brinkhursts”, which may have been part of the provisions for the funeral. Benjamin was buried on the 17th February.

Benjamin was originally from Wartling, and after moving to East Hoathly, worked as a labourer for John Vine, starting in September 1760. He married Ann Dalloway in April 1762 and gained the right of settlement in East Hoathly in 1769.

Benjamin and Ann had three surviving children: Benedicta (born 1771), William (1773) and John (1776). Two children born to the couple in 1763 and 1764 had died young. When Benjamin died Benedicta was eleven, and William and John nine and six respectively.

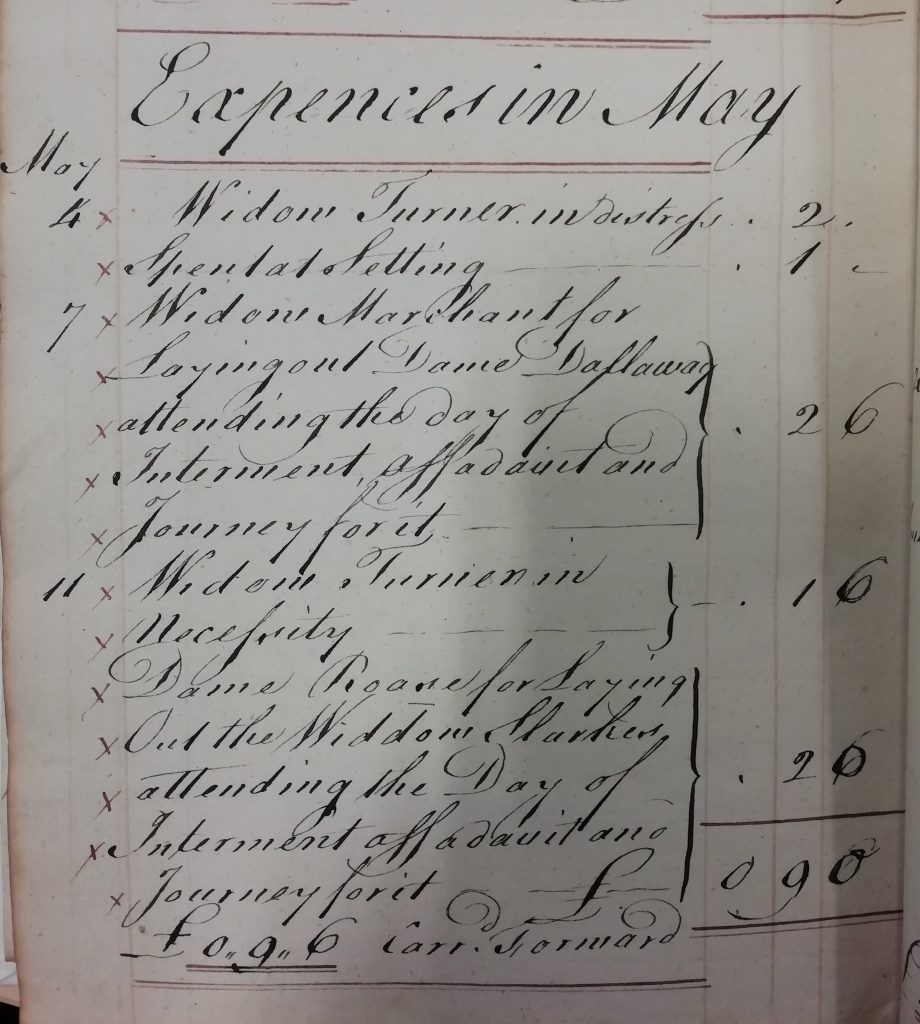

The family had received help from the parish prior to Benjamin’s death, but would be more reliant on its help after the death of the breadwinner. During the period immediately before and after her father’s death it was Benedicta who collected the family’s groceries from Thomas Turner’s store, perhaps because her mother was nursing Benjamin. Subsequently Widow Brinkhurst was usually named as the recipient by Turner in his invoices.

Turner supplied candles and soap to the family. He supplied foodstuffs: cheese (4 lbs at a time), butter and sugar, as well as condiments – salt and pepper. For flour the family went to Charles Fielder the miller, getting through 4 gallands (sic) every week to a fortnight. They ate mutton, which seems to have been the staple meat of the poor of the parish, and this Benedicta obtained weekly from the butcher, Richard Fuller. Fuller’s bill to the Parish for the first part of 1783 itemises weekly supplies of mutton to Benedicta from the 1st February to the 15th April.

In the bills which survive it is startling how often the Brinkhurst boys had their shoes mended, (in common with other children in the parish). In one of his bills Thomas Davy remarks plaintively that he had mended William’s shoes “several times”. There is only one instance of Benedicta’s shoes being mended in the surviving bills, in April 1782.

If the boys were provided with new shoes once or twice a year, their feet must soon have outgrown their footwear, and that, and the active life they led, would help to explain the frequent need for repair.

In December 1786 when Benedicta was fifteen, and the boys thirteen and ten, the children’s’ mother Ann died, and the record of her burial on 15 December was annotated “pauper” (not the case for her husband). She seems to have been ill for some time as Mr Paine the surgeon had supplied medicine worth 13 shillings the previous September.

After that the boys became “parish children”. They lodged with parishioners who fed and housed them, and the parish was billed for their keep. The Mr Turner, who was responsible for William may have been Thomas Turner himself.

At the beginning of February 1786 Benedicta received a new pair of shoes, costing 4s 6d. She was rising 16 at this date, and it seems quite old for a child at that time to be dependent, and not expected to be at work.

Village inhabitants were usually provided with a set of clothes prior to looking for a position. That there is no record of Benedicta being outfitted other than with shoes may be because the records have not been transcribed or are incomplete. In contrast, there are bills for a waistcoat for Benedicta’s brother John in the spring of 1790, followed by a hat and hose later in the year, and in 1791 when he reached the age of 15 he was provided with a pair of shoes and nails, presumably a preliminary to starting to look for work.

Benedicta may have left the village to find work, but the boys stayed on in East Hoathly as parish children, continuing to provide the shoe menders with work.

Benedicta re-surfaces in the records at the age of twenty four, living in Lewes. In July 1795 her marriage banns were read in the parish of All Saints Lewes. Benedicta married Stapley Ade, a cordwainer, of St Michael’s Parish Lewes, on 26 July 1795. Her husband was forty eight years old to Benedicta’s twenty, which makes one wonder how she met him. Maybe he had been her employer prior to their marriage (although they were recorded as living in separate parishes). Their first child Ruth was born on December 25th in the same year, which indicates that Benedicta was already pregnant when the couple married.

The couple had five children: Ruth (born 1795), George (1797), Mary (1801), and John (1803) and Alfred (1808). Only the oldest two lived beyond infancy. The fifth child, Alfred Stapley Ade, was baptised in September 1808, and buried on 5 March 1809. Shortly after, on April 16 1809 there is a burial record for Benedicta, whose age was recorded as thirty six years, although her birth in 1771 would make her thirty eight.

Sources

www.Familysearch.org accessed 18 January 2019

PAR378/31/3/8 for settlement examination of Benjamin Brinkhurst

PAR 378/1/1 Early registers (1560-1812)

PAR378/31/3/19, PAR378/31/3/20, PAR378/31/3/21, PAR378/31/3/22