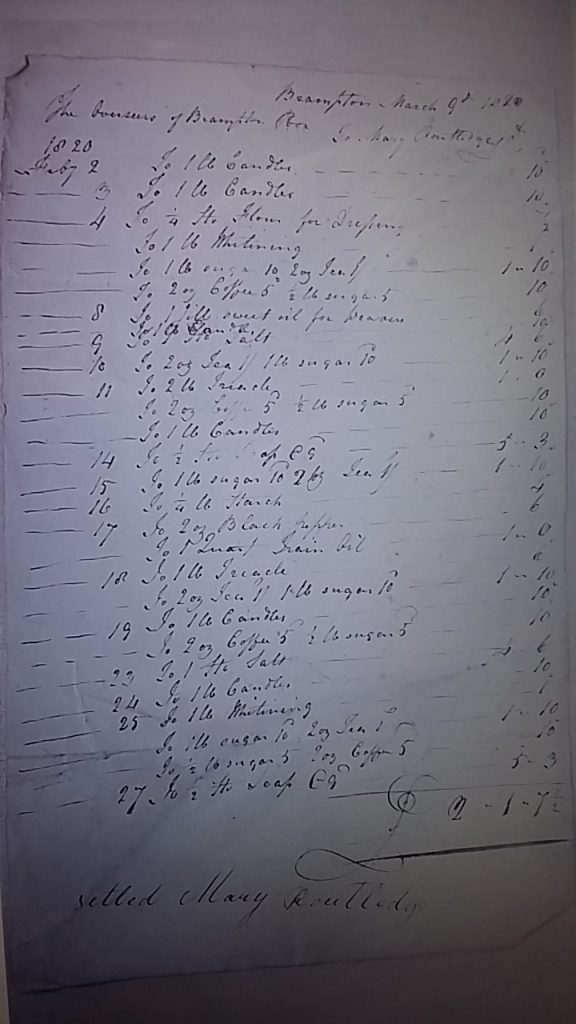

Robert and Mary Routledge ran a Grocer’s business in Brampton. Mary was referred to as Molly Calvert in the Brampton Parish Register when their children were baptised. They were baptised in nearby Lanercost, Mary 23 August 1766 and Robert 17 June 1760. They also married there 7 January 1796.[1]

Mary Routledge supplied goods to the poor of Brampton, but it is not known if this was a regular order that she had to supply them [2]

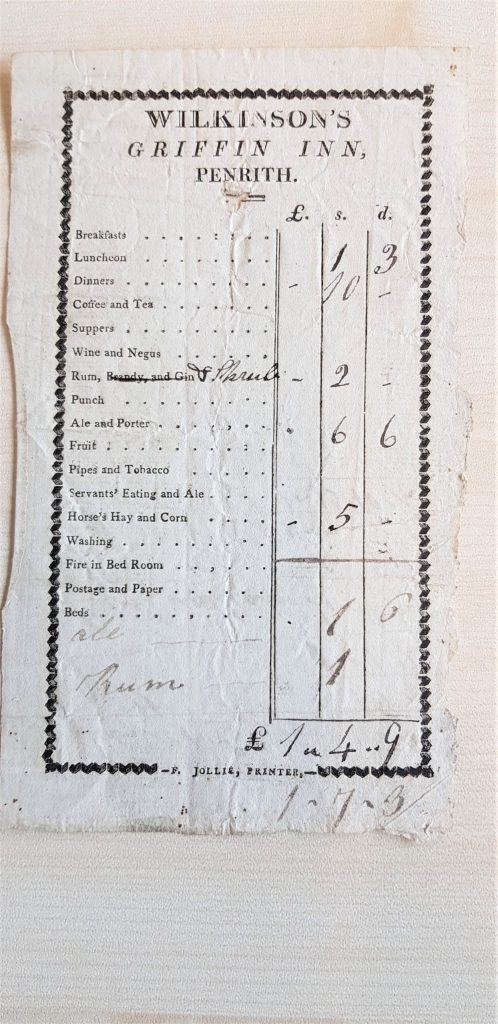

A bill for goods supplied in February 1820 and settled promptly 9 March 1820 totals £2.1s.7 1/2d for the month. Items included being:-

1 lb candles, 10d

1 lb whitening 1d

1/2 lb starch 4d

1/2 stone soap 9d 5s. 3d

1 gill of sweet oil for weavers, 6d

1 stone salt, 4s 6d

2 oz black pepper, 6d

1lb treacle, 6d

2 oz coffee, 5d, 1/2 lb sugar, 5d 10d

Typically tea or coffee were itemised together along with the sugar.

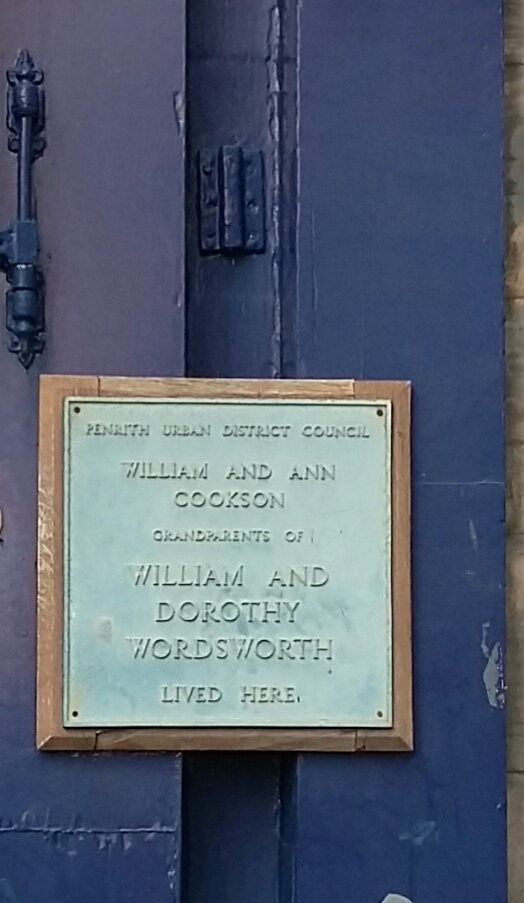

Robert Routledge is listed in Jollie’s 1811 trade directory as a Grocer.{3].As occurred with other women Mary took over the business from her husband after his death 12 July 1815. At this time of their eight children 7 were still alive, Catherine (1808-1811) having died young. The oldest 18 years the youngest 3 years .[4]

Mary is listed in both the 1829 [5] and 1834 [6] trade directories. In 1834 at Front Street, Brampton where she is also a dealer in earthenware. Her business near fellow female Grocers, Elizabeth and Jane Tinniswood who also sold confectionery.

When Robert died he left a will (at this time unable to access), [7] which may reveal under what basis the business was left to Mary as well as other assets. After Mary’s death 21 May 1843 [8,9] the business continued with the two unmarried daughters, Margaret (1797-1880) and Ann (1807-1881) not the son’s.They continued to be listed in the trade directories [10] and on subsequent census up till 1871 as Grocers and China Dealers . When they [Margaret and Ann] died within 6 months of each other they both left reasonable healthy estates of just over £800 each. It is not known if any other family member took over from them.

Of their siblings eldest daughter Mary (1797-1881) married David Latimer in 1818. The son of David Latimer Cabinet Maker from whom a voucher also survives. [11] David was principally an agricultural labourer. He and Mary had a large family some of whom died at a young age.They remained in Brampton.

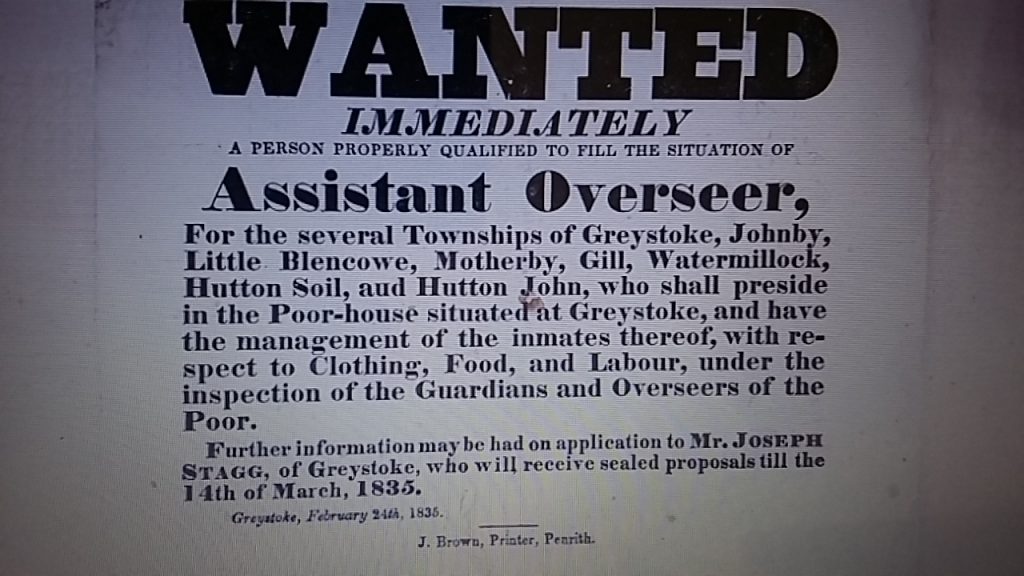

Eldest son John (1800-1859) was appointed High Constable in Brampton in 1834, where he may have gained additional income from the letting of a farm Kingwater near Lanercost.[12 ]. He was referred to in the Carlisle Journal as being known in Brampton as “Laird” Routledge . They also go on to say that when his house was demolished in Brampton a small bricked up window was found where as Relieving Officer in 1836 he would hand out relief to the poor.[13]

Two son’s Robert and William left Brampton.. Robert (1803-1861) was an Inland Revenue Supervisor in Manchester, while William (1804-1875) became a Clergyman and Schoolteacher in Devon.

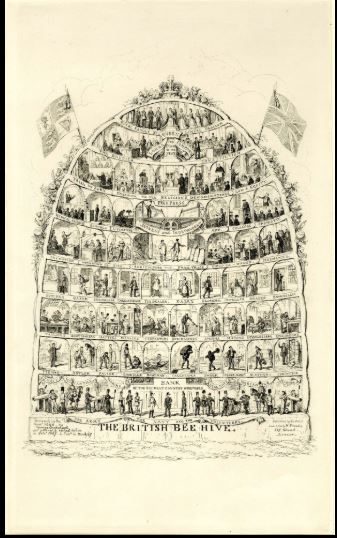

Youngest son George (1812-1888) [14] served an apprenticeship with Charles Thurnam, Publisher in Carlisle from 1827 to 1833 before moving to London. Initially working for others and supplementing his income by working in the Tithe Office. He established his own Bookselling and Publishing business in London and New York . He returned to the place of his birth in later life; being a wealthy man he bought the land on which stood the cottage of his birth.as well as other estates once belonging to his forebears. Described by the local newspaper as a pioneer of cheap literature in this country, beginning life in a humble way and gaining distinction through energy and intelligence[15]. When he died 13 December 1888 his disposable estate was valued at £95.139.

Sources

[1] England Select Marriages, 1538-1973 [accessed at ancestry.co.uk., 4 March 2020]

[2] Cumbria Archives, PR60/21/13/7/8, Brampton Overseers Voucher, 9 March 2020 or PR60/21/13/6/8 line 2-30

[3] F. Jollie, Jollies Cumberland Guide and Directory (Carlisle: 1811).

[4] findmypast.co.uk. [accessed 4 April 2020]

[5] Parson & White’s, Principle Inhabitants of Cumberland & Westmorland (1829).

[6] Pigot’s, Directory of Cumberland and Westmorland (1834)

[7] Cumbria Archives, Wills, PROB/1815/W614

[8] Cumbria Archives Wills, PROB/1843/W912

[9] Carlisle Journal, 27 May 1843, p. 3 col. g.

[10] Slater’s, Cumberland Directory, 1855.

[11] Cumbria Archives, PR60/21/13/5/11, Brampton Overseers Voucher, March 2 1815.

[12] Carlisle Journal, 11 December 1841, p.1 col. d.

[13] Carlisle Journal, 7 January 1898, p.5. col. d.

[14] England Births and Baptisms Parish Records, 1538-1955 accessed at findmypast.co.uk

[15] Carlisle Journal, 18 December 1888, p.2 col. d.

This is a work in progress subject to change with further research.