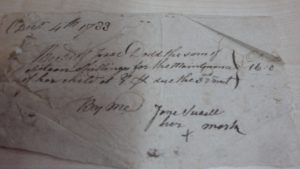

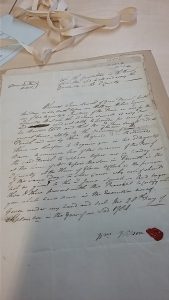

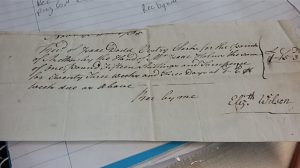

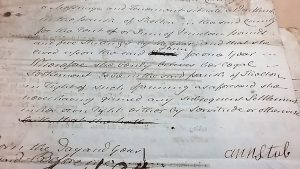

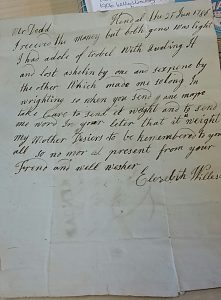

One of the vouchers from Skelton initially caused a bit of a puzzle. This was resolved when it became apparent that it was from Elizabeth Wilson to Isaac Dodd, the Skelton vestry clerk. This was not the only letter that Elizabeth had written to Isaac. Like Elizabeth’s previous letter, (see https://thepoorlaw.org/2018/12/29/elizabeth-wilson-fl-1785-1788/), this one, dated 25 June 1786, came from Kendal and was to be left at the Black Bull, Penrith.

It begins ‘I received the money but both genes was light’. Once more she was talking about guineas given to her and their validity. Their light weight was the source of her unease and the consequent effect this had on its monetary value.

The Guinea was minted in Britain between 1663 and 1814. It weighed approximately one quarter ounce of gold. Its value could fluctuate with the rise and fall in the price of gold. By 1717, however, its value was fixed at 21shillings. The guinea Elizabeth was given was most likely a George III guinea. During his reign these were issued in six different obverses and three reverses. From 1761 to 1786 the guinea showed a crowned shield on the reverse. In 1787 the guinea was called the ‘spade guinea’ referring to the crowns shield in the shape of a spade on the reverse.

It was the weight of the coin that concerned Elizabeth. These coins not only lost weight with wear but irregularity of shape meant they were the target of counterfeiters; clipping being one such offence. Pieces were shaved from the edge of the coin to melt down for the gold to be sold or made into other coins. Elizabeth was obviously aware of the problem of counterfeit coins. Warnings appeared in the newspapers of the time. The following appeared in the Newcastle Chronicle:

Counterfeit guineas are now in circulation in Whitehaven which seem to have been produced only a few days since. They are much thinner than the real guinea poorly relieved and so badly executed that they can pass upon none but the very ignorant.

In 1786 the Derby Mercury reported concerns about counterfeit copper coins being released into general circulation and the impact it would have on the lower classes. The Mayor offered a reward of five guineas for help in bringing those responsible to justice. Nearer to Skelton at a later date and at the instigation of the Mint, Richard Irving was prosecuted by Thomas Ramshay and received a sentence of six months hard labour for knowingly possessing counterfeit coins when arrested by Hesket Newmarket Poorhouse doorway. Previously he had been a husbandman of good character, but was now selling pots and living in camps at the hedge-sides.

Another profitable crime was that of ‘uttering’. This often involved a genuine coin or coins being swapped for a counterfeit one while making a purchase. Women were often involved in uttering or passing of bad coins. The notion being they were more easily trusted and able to dispose of the false coins.

Elizabeth Wilson’s upset seems to be directed at the coins she has been sent rather than any malice towards Isaac Dodd. She finished her letter: ‘My mother desiers (sic) to be remembered to you all so no moor[more] at present from your frend (sic) and well wesher (sic). However by November 1787 she is still having trouble with the weight of the guinea.

Sources

Cumbria Archives

PR 10/V/12, Skelton Overseers’ Voucher, Elizabeth Wilson to Isaac Dodd, 25 June 1786

Newspapers

Newcastle Chronicle, 4 August 1781

Saunders Newsletter, 20 September 1786

Derby Mercury, 19 December 1786

Carlisle Journal, 19 October 1839

Websites

www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0 March 2018 accessed 13/01/2019

https://wwwlondonmintoffice.org accessed 13/01/2019

This is a work in progress, subject to change with further research