Jane Gate was born in Dalston and baptised there on 14 July 1795. The youngest of six children, her elder siblings were William (b.1784), Robert (b.1786), John (b.1789), and twins Elizabeth (1792-1795) and Margaret (b.1792). Her father Jonathan (b.1755) was listed as a labourer in the parish register. Jane’s mother Frances Mathews (c.1760-98) died when Jane was three years old. [ 1 ]

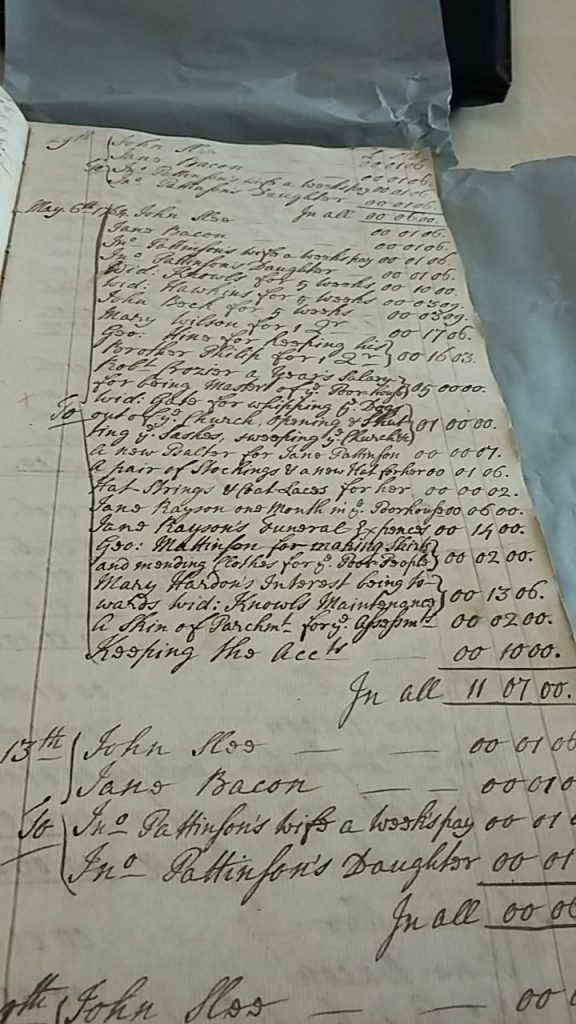

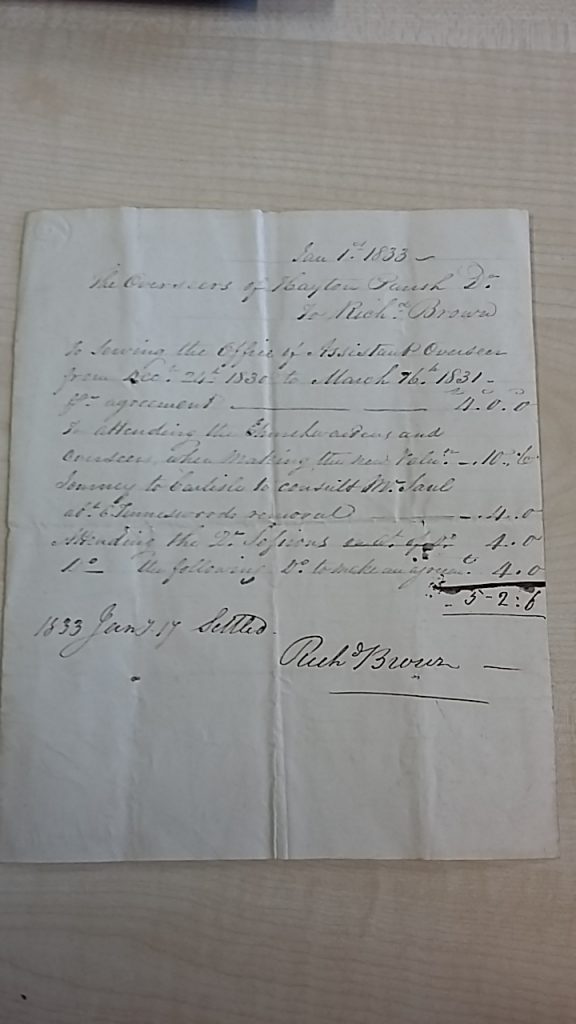

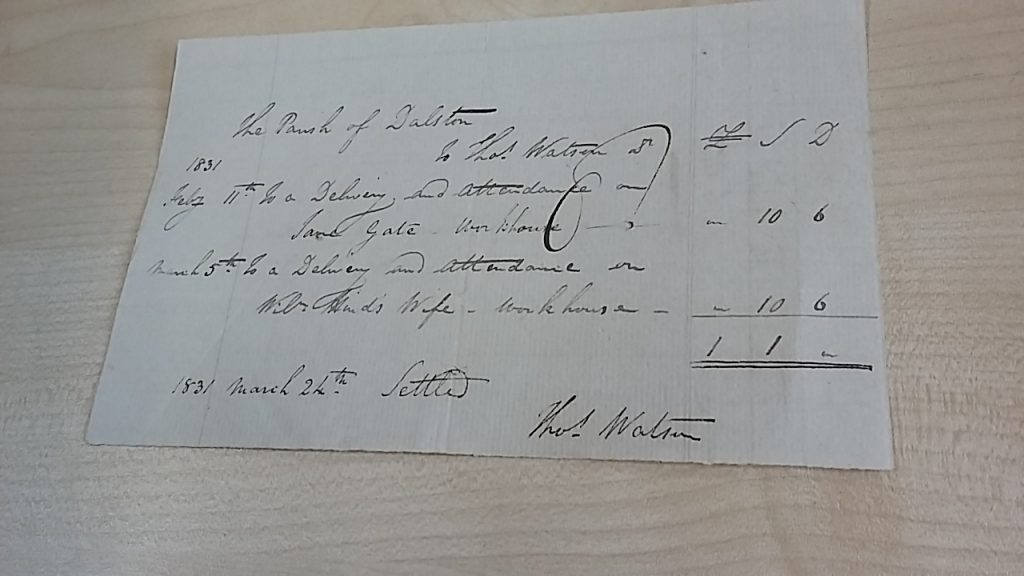

Jane Gate’s name appears on a voucher dated 11 February 1831. A payment for 10s. 6d was made to Thomas Watson (1801-1833) surgeon: ‘to a Delivery and Attendance on Jane Gate ,Workhouse’.[ 2 ] This refers to Jane’s son William who was baptised in Dalston 7 April 1831. This is not the only time that her life converged with the physicians of the parish. To one encounter with Dr Daniel Wise in 1824 she may have owed her life .

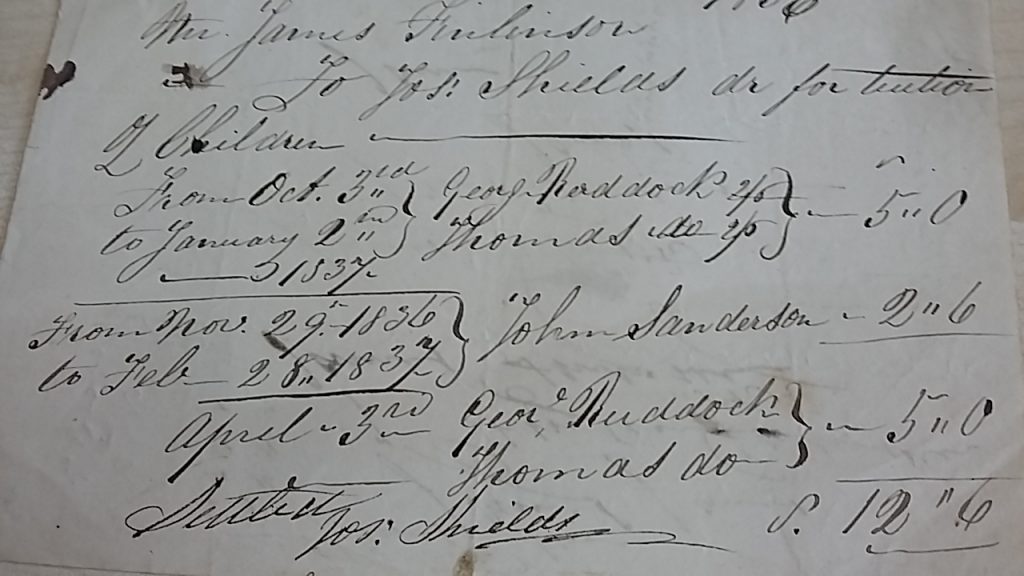

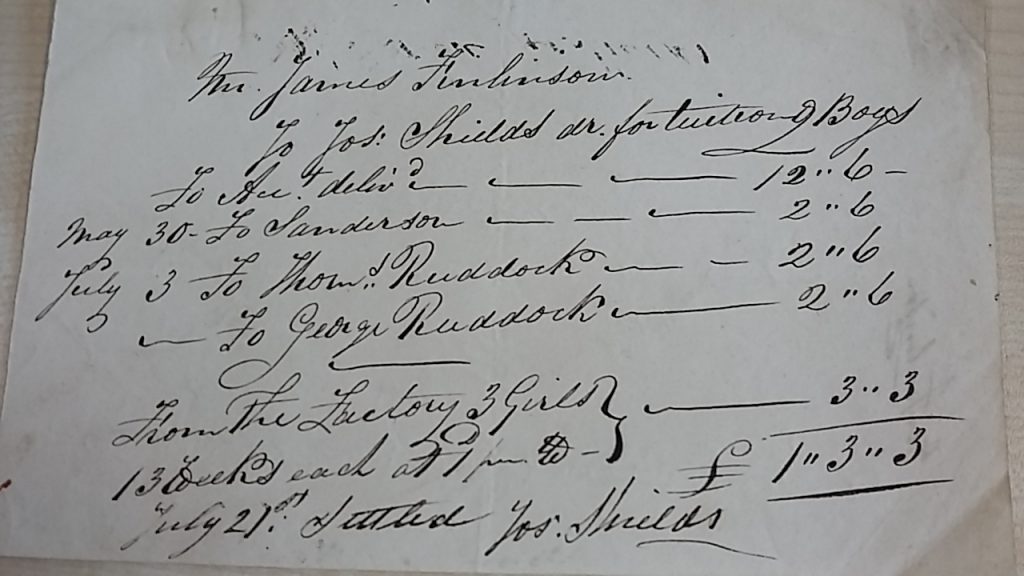

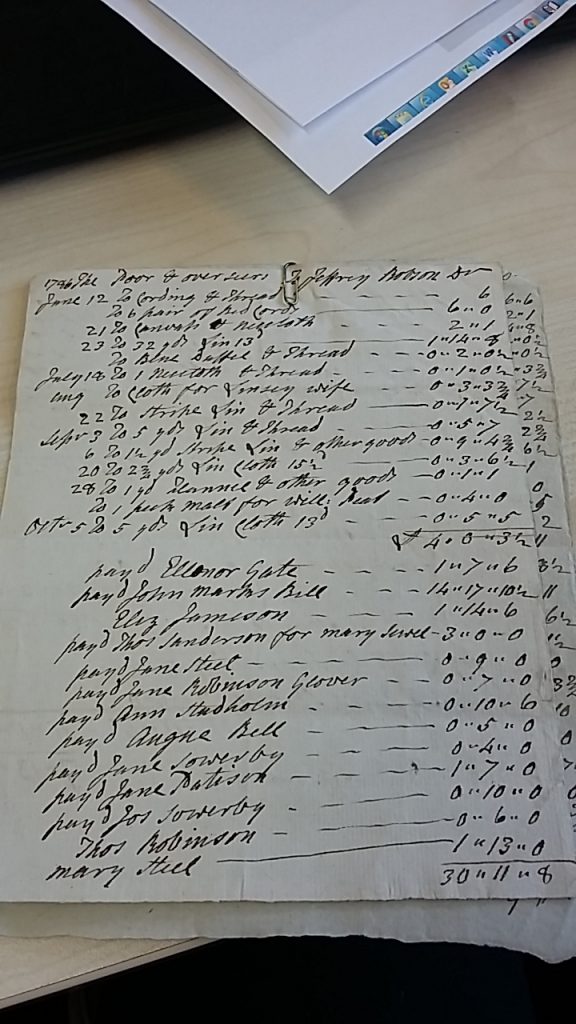

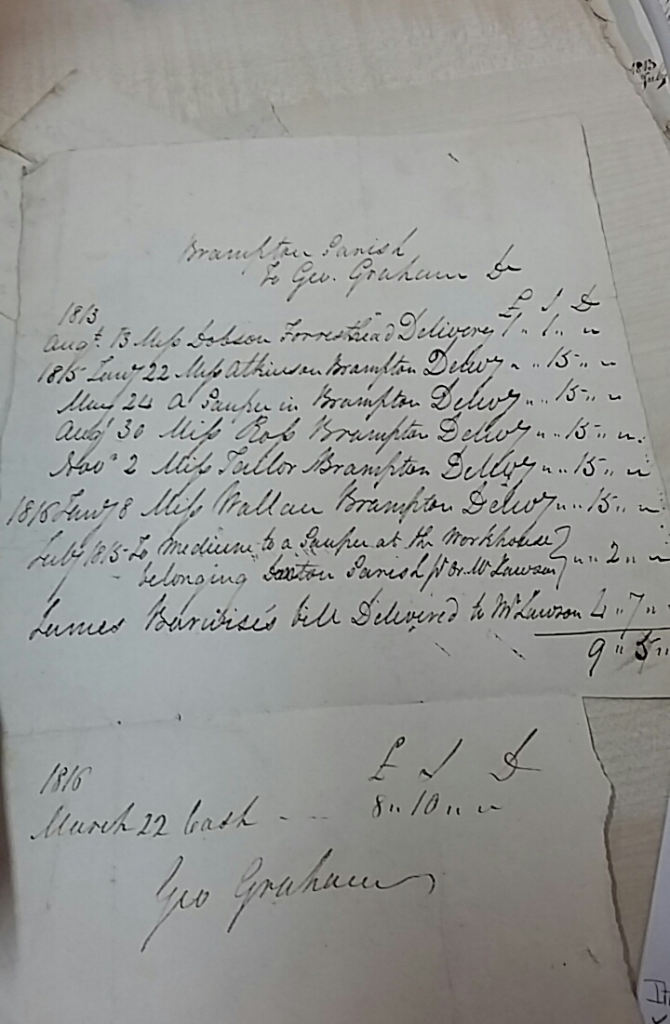

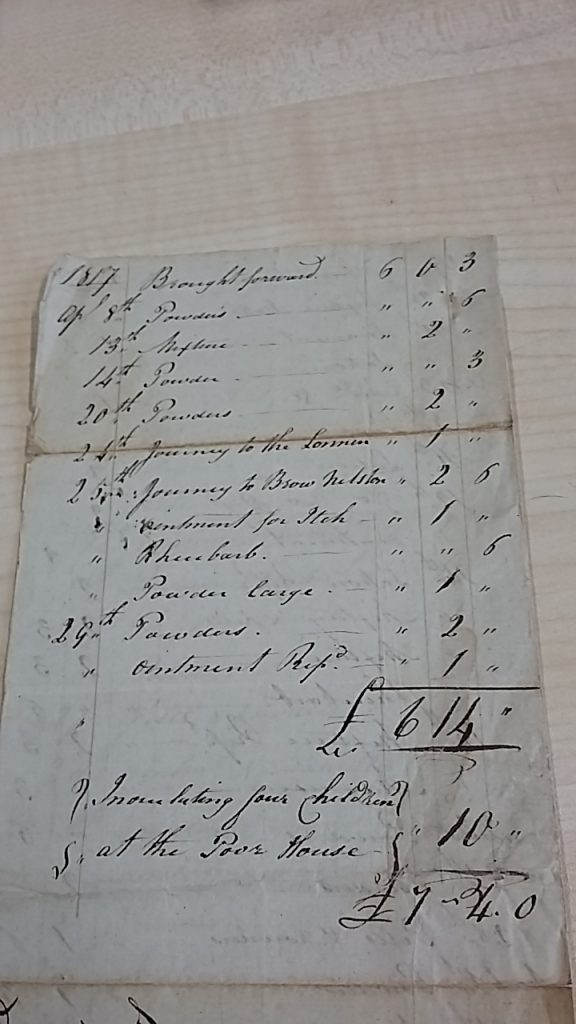

Daniel Wise (1781-1829) was born 1 May 1781 Seaville, Holme Cultrum Parish, the son of John and Dorothy Wise. It is not known when he became a practicing doctor although he was in the Dalston area in 1815.[ 3 ] Three vouchers exist with a list of his expenses sent to the overseers of Dalston. Common items supplied include pills 1s 6d, powders 6d and 2s.0, a blister and ointment 1s 0d, while also including the inoculation of children at the poorhouse and attending deliveries. [ 4 ]

In 1823 Jane Gate was living in the Townhead area of Dalston, an area near the church and the centre of the village. Various newspapers reported on the events in Jane’s house that night, although they all vary slightly in how they relate the facts. In summary, her neighbour Mary Irving like others suspecting she may be pregnant called to see how she was. Finding Jane unwell she went for Margaret Scott who brought Betty Irving, Mary’s mother, as well as Jane Irving and Mary Atkin. Quite a few neighbours appear to have been in the house trying to determine Jane’s circumstances. Eventually, after denying she had given birth, Jane when asked by Mary Atkin if if she had given birth and where it was replied ‘upon the coals in the coal hole’. There they found a male infant dead covered in coal dust. It was also revealed that Jane had a illegitimate daughter, Frances, about 5 years old living with her.

Dr Wise was sent for by the overseer and seeing the injuries to the dead infant felt it had come to some malicious harm. A subsequent inquest conducted by Richard Lowry at overseer Thomas Martin’s house, the King’s Arms, reached a verdict of ‘wilful murder’ against Jane Gate and she was committed under a coroner’s warrant for trial. [ 6 ] Jane could not be removed to prison and her subsequent trial was postponed as she was not considered well enough. The coroner bound her over to the churchwardens and overseer to prosecute. It was reported that Jane had a ‘dangerous and infectious illness’. Jane Gate had smallpox.[ 7 ] Her trial was postponed until the spring assizes.

At the Cumberland Assizes (9 March 1824) Jane faced an indictment of murdering her own child. Appearing before the Grand Jury, she pleaded ‘not guilty’. She was appointed council to represent her as she had none.

Jane’s daughter Frances (1819-85) was asked to give evidence. Frances, on being questioned, said she did not know how old she was or what would become of her if she told a lie. No more was asked of her.

Mary Irving, one of the first to enter Jane’s house, described where Jane Gate lived. A house with one room downstairs, one up, a kitchen, stone flags on the floor and a fire, ‘Very near the public road where anyone can see in’. Many other women also lived there who knew her well. [8]

Evidence given to the coroner was simulary repeated by some of the women who had been present. No mention was made of any employment that Jane may have had or help from the parish.

At the coroner’s inquest, Dr Wise said that the infant had injuries about the head enough to cause death. He was unable to give a positive judgement as to whether the male child was born alive, or if the injuries were deliberate or incidental. [9]

Justice Holroyd directed the jury. He pointed out that there was proof she had concealed the child, but as the law had changed, where previously the mother of a dead child born in secret would be guilty of murder Lord Ellenborough’s Act meant the circumstances had now to be enquired into. She had not dealt with the child as if she meant to murder it although there may be a strong suspicion. Jane Gate was found ‘not guilty’ of murder but sent to Cockermouth House of Correction for two years for the concealment of the child.[10] None of the newspapers give any account of anything Jane Gate may have said in her defence other than her reply, ‘Not Guilty’. One newspaper went as far as to provide judgement of Jane, calling her ‘a wretched woman’.[11]

By 1827 Jane was living in Whitehaven about 14 miles from Cockermouth. She is receiving payments from the overseers of the poor. 1s 6d per week.[12 ] Three letters from Jonathan White asking for the money paid to her to be refunded by the Overseers at Dalston exist.

Jane must have returned to Dalston before her son Robert was born in 1831. By 1841 Jane, and her children Frances and Robert were living together. Jane and Frances were working in the cotton industry. They remained in Dalston, but poverty was never far away. When not working as agricultural labourers or in the cotton industry they were listed as paupers or recipients of parochial relief on subsequent census returns. Jane died December 15 1867 while living at Whitesmith Buildings, Dalston; Frances on 4 January 1885 at Skelton’s Yard, Dalston; and William on 13 February 1900 at Dalston.

Dr Wise died on 13 March 1829 aged 46 years. He and his wife Ann Hayton had three children, Joseph (1810-1830), Dorothy Wilson (b.1812) married to Dr James Allen (who died in Bedlam Hospital, London 1877) and Ann (b.1816). [13]

References

[1] Cumbria Archives. PR 41 Dalston St Michael Parish Register, 1570-2016

[2] Cumbria Archives. Dalston Overseers’ Voucher, SPC44/2/48/73 line 1 24 march 1831

[3] Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser, 12 September 1815, p3 col a

[4] Cumbria Archives, Dalston Overseers’ Voucher, SPC44/2/51/1, June 1817; SPC44/2/51/2, 15 February 1816 – 24 April 1817; SPC44/2/51/3, 22 August 1814- April 1815, bills to the Overseers of the Poor from Daniel Wise

[5] Carlisle Patriot, 12 July 1823 p 4 col. d

[6] Bell’s Life, 20 July 1823, p4 col b (accessed 19 August 2019 at Find My Past.co.uk)

{7] Westmorland Gazette, 16 August 1823, p3 col e

[8] Carlisle Patriot ,13 March 1824, p1 col e,f

[9] Carlisle Patriot 13 march 1824, p2 col a

10]Cumbria Archives. Q/4, Conviction Books 1791-1891, Lent 1824

[11] Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Whitehaven Advertiser, 15 March 1824, p2 col e

[10]Cumbria Archives, Q/4, Conviction Books. 1791-1891, Lent 1824.

[12] Cumbria Archives, SPC 44/2/66/30, 19 August 1827; SPC 44/2/66/32 22 September 1827; SPC 44/2/66/38, 5 December 1837.

[13]ancestry .co.uk