The reconstructed life of Sarah Oliver is a combination of a

few ‘definitelys’ and many ‘maybes’. She is most visible in historic records as

a widow, but even then the traces she left are few. She has come to attention because she supplied Brampton’s

overseers with groceries.

The Marriage Bond Index held at Carlisle, lists Sarah Bell, a minor, who married Henry Brough Oliver, bachelor.[1] The bond was dated 22 October 1798. Sarah’s mother Jane was her guardian and the bondsman was Thomas Bell. This may be Thomas Bell the younger who ran the Howard Arms in Brampton and or Thomas Bell the elder, of the Bush Inn and a carrier operating a service between Carlisle, Brampton and Newcastle.[2] There were, however, many people in Brampton with the surname ‘Bell’.

There is a record of a Henry Brough Oliver born 11 November

1776, baptised 10 December 1776, at St John’s, Smith Square, Westminster, the

son of Richard and Jane Oliver.[3] A

Henry Brough Oliver and a Richard Oliver served as officers in the Eighth (King’s)

Foot Regiment c.1792–98.[4]

Henry and Richard Oliver of Intack, Cumberland, both held game certificates and

were thus licensed to shoot game.[5]

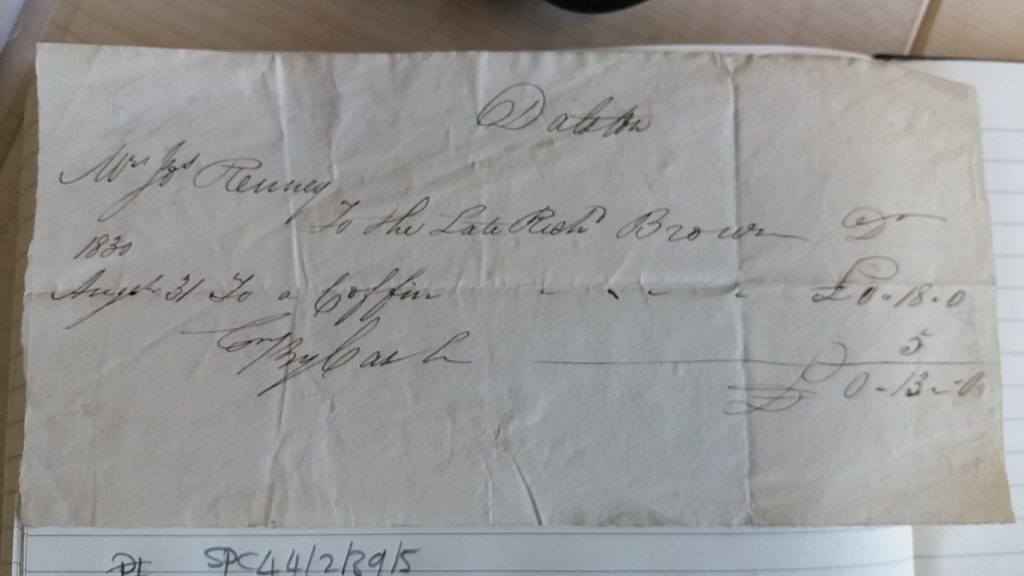

Henry Brough Oliver died in 1808, and was buried in Knarsdale, Northumberland.[6]

Henry and Sarah Oliver had several children: twin sisters,

Elizabeth and Jane, baptised in Brampton 24 March 1803; and two other twin

sisters Isabella and Sarah baptised in Brampton 13 March 1807.[7]

There was possibly a fifth daughter Mary born 1 September 1808, in Knarsdale.

There was also a son Richard Brough (23 January 1800) who became a doctor with

a practice in Carlisle, before becoming the medical superintendent of Bicton

Heath Lunatic Asylum, near Shrewsbury.

The Olivers are not listed in the Universal British Directory of the 1790s, but S. Oliver is listed as a grocer in Jollie’s 1811 directory.[8]

Henry was a cotton manufacturer, but a notice in the Tradesman or Commercial Magazine, and

later in the London Gazette show that

a commission of bankruptcy was brought against him in July 1808.[9] In 1811 the London Gazette, carried the following notice:

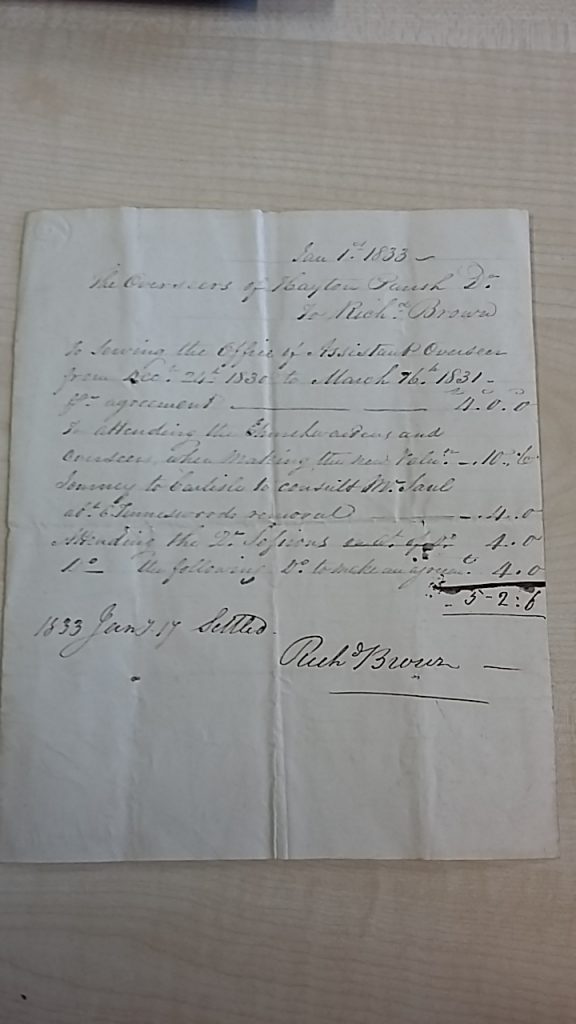

The Commissioners in a Commission of Bankrupt, bearing Date

the 6th Day of July 1808, awarded and issued forth against Henry Brough Oliver,

late of Brampton, in the County of Cumberland, Cotton-Manufacturer, Dealer and

Chapman, intend to meet on the 26th Day of December next, at Eleven

of the Clock in the Forenoon, at the Bush, in the City of Carlisle, in the

County of Cumberland, in order to make a Final Dividend of the Estate and

Effects of the said Bankrupt; when and where the Creditors, who have not

already proved their Debts, are to come prepared to prove the same, or they

will be excluded the Benefit of the said Dividend. And all Claims not then

proved will be disallowed.[10]

Despite the declaration that a final dividend was

to be paid on this occasion, this was not the end of the matter. Fifteen years

later, another notice in the Gazette

called the creditors of Henry Brough Oliver to a meeting at the Office

of Messrs. Mounsey, Solicitors, Carlisle, ‘to take into consideration and

determine upon the best mode of proceeding as to a certain sum of money, lately

become due to the said Bankrupt’s estate; and on other matters and things

relative thereto’.[11]

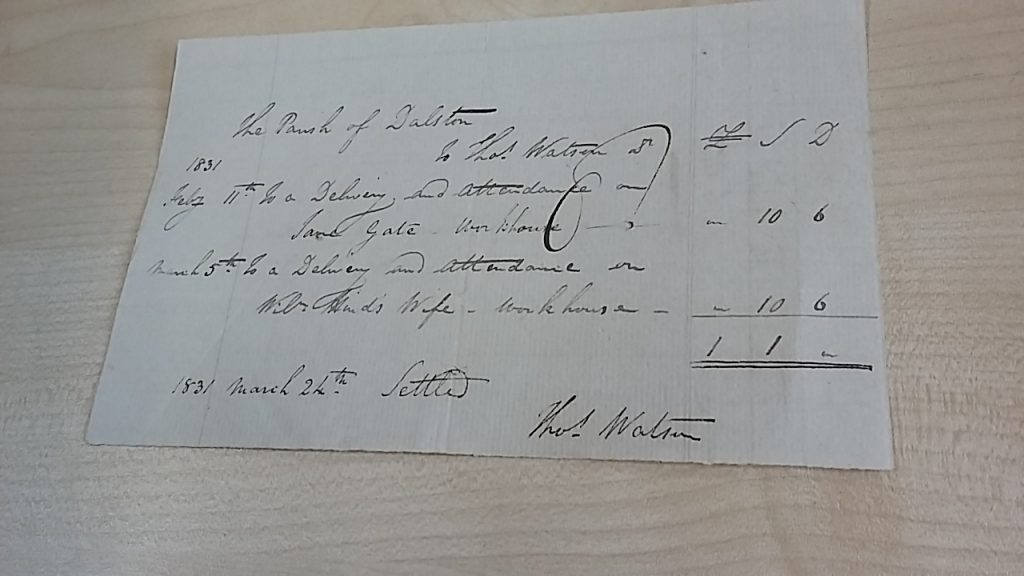

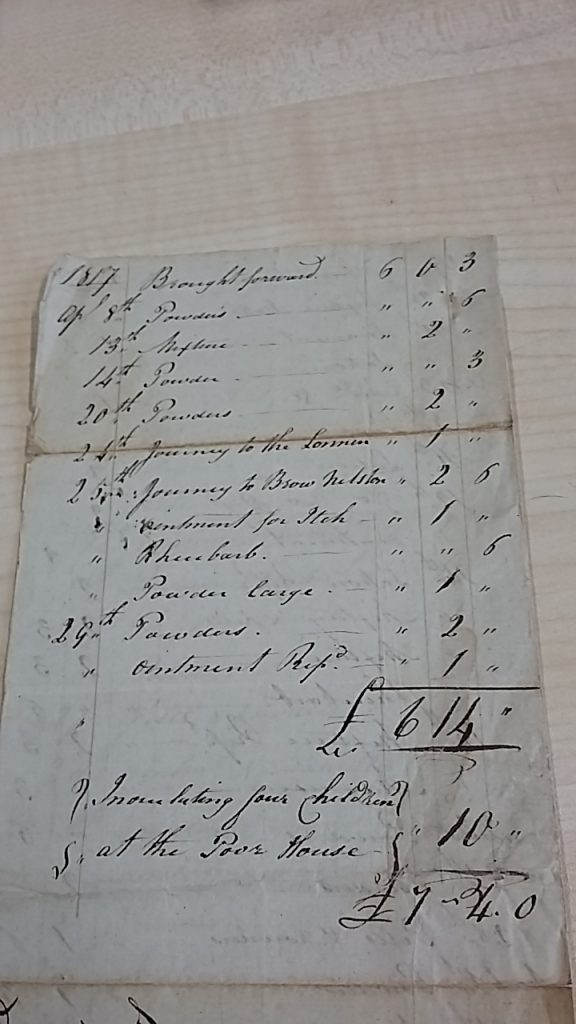

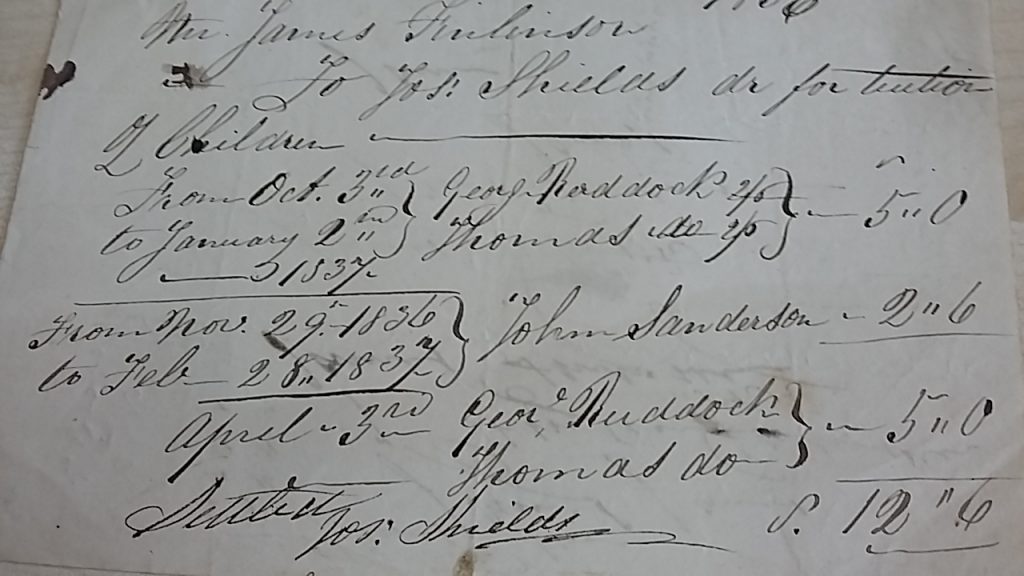

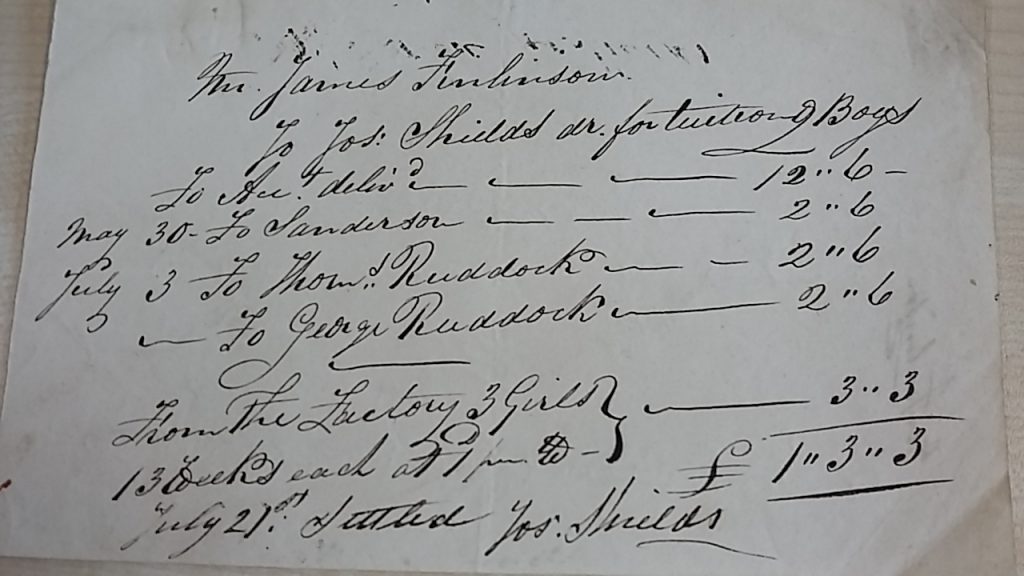

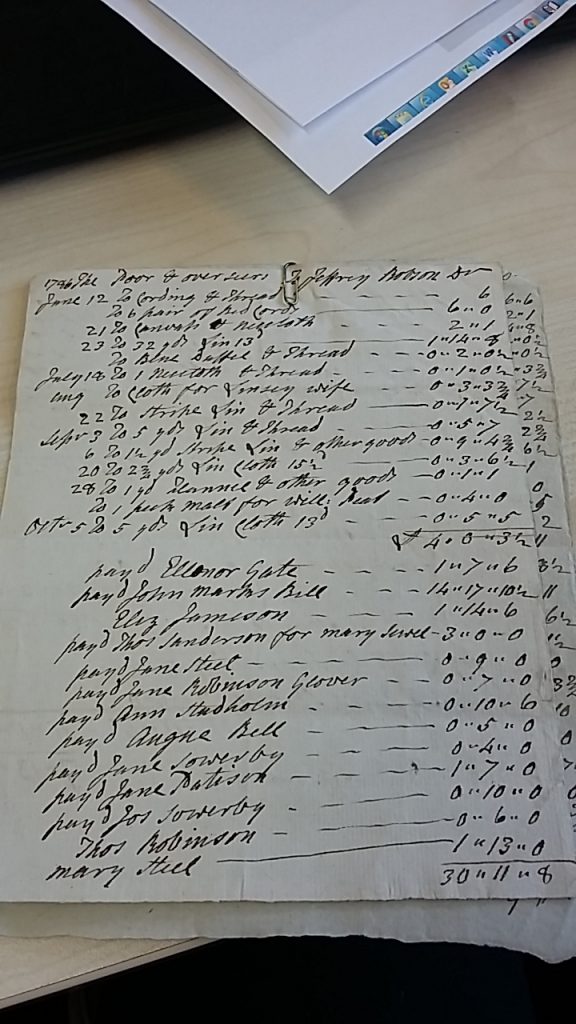

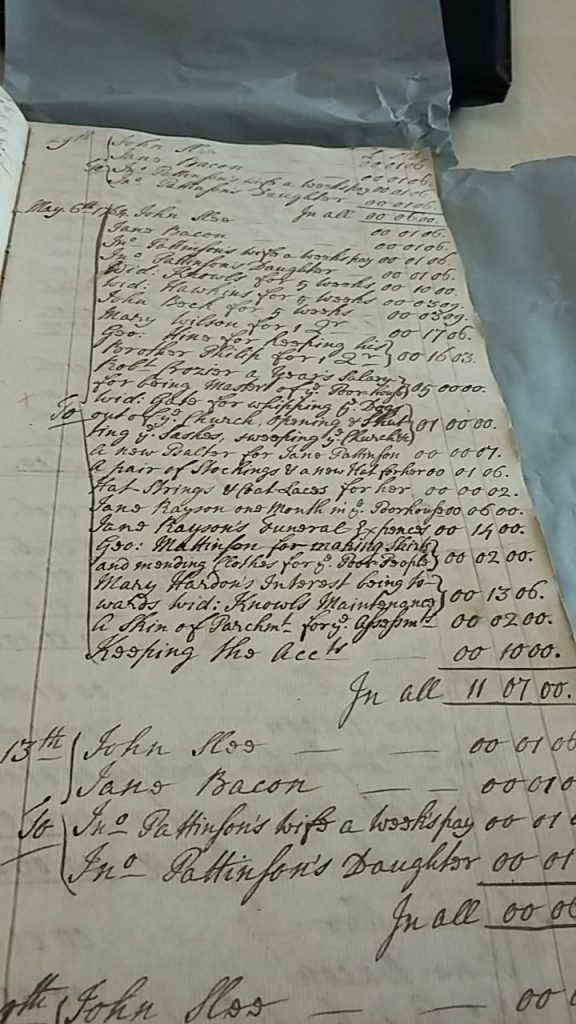

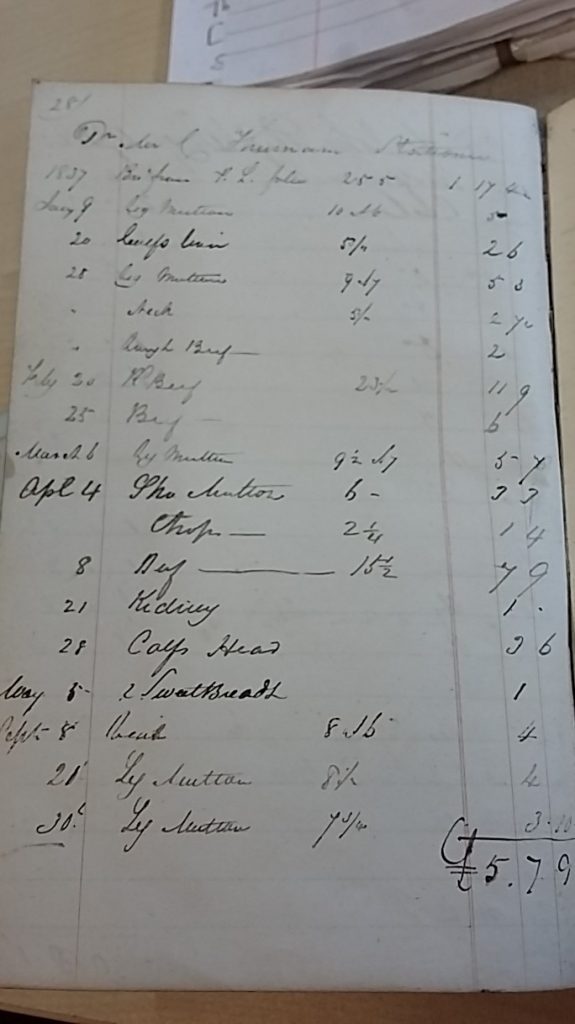

As a grocer, Sarah Oliver was in regular contact with Brampton’s overseers between 1818 and 1820.[12] In the 139 days between 22 December 1818 and 10 May 1819, for example, purchases were made on 70 separate occasions. Some of her stock came from fellow Brampton grocer Isaac Bird. She settled her account with him in cash, and once in tobacco.[13]

Oliver supplied Brampton’s workhouse with imported

items including tea, coffee, sugar, and pepper; and domestic items including,

candles, soap, starch and flour.[14] Oliver did not sell a

more restricted range of goods than male grocers also located in Brampton. Her

goods were identical in name to the flour, soap, starch, blue, candles,

tobacco, barley, tea, coffee and sugar supplied by Joseph Forster.[15] Moreover, prices paid per stone, pound or

ounce, were very similar. It is entirely possible that the quality of goods

differed, but neither the vouchers nor Forster’s ledger make such distinctions

possible.

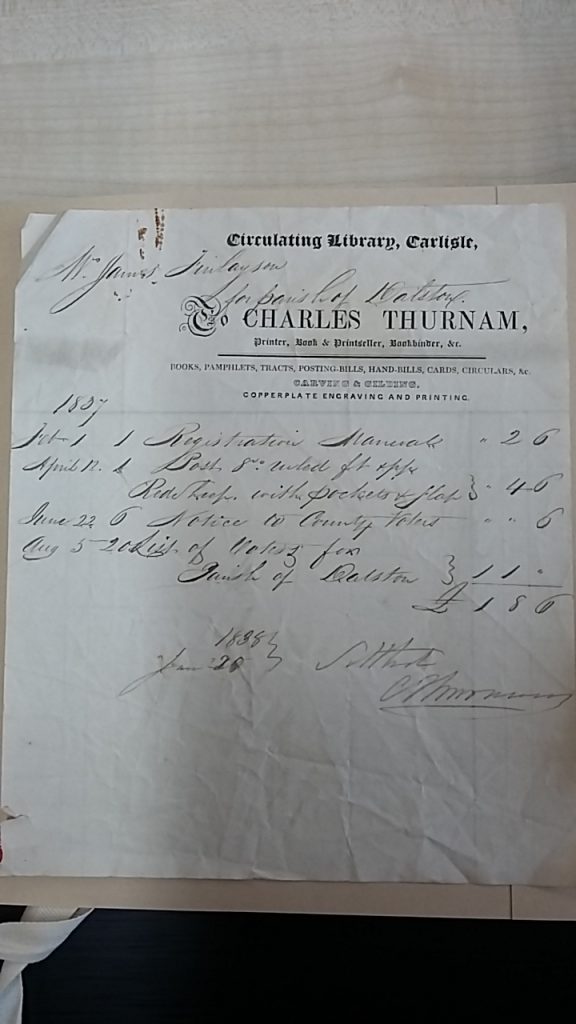

In the early 1820s Oliver moved her business to Scotch Street, Carlisle, where she acted as agent to the London Genuine Tea Company.[16] Daughters Elizabeth and Jane, became milliners and dressmakers; they are listed in Jollie’s1828–29 directory, as also being resident in Scotch Street.[17] In 1834 Richard Hind, ironmonger, of English Street, Carlisle, married Mary Oliver, of Scotch Street.[18]

Sarah Oliver died Carlisle in 1852. Her death was reported in the Carlisle Patriot: ‘Yesterday, in this city, aged 52, Sarah, relict of the late Mr. Henry Brough Oliver, of Brampton, deeply lamented by her family’.[19]

This is a work-in progress, subject to change as new research is conducted.

[1]

Cumbria Archives, Carlisle, Marriage Bond Index.

[2] Peter Barfoot and John Wilkes, Universal British Directory of Trade,

Commerce and Manufacture, 5 vols. (London: c.1795), V, Appendix, 27–9.

[3] St

John the Evangelist, Smith Square, London, born 11 November, Baptised 10 December 1776,

Henry Brough, son of Richard and Jane Oliver.

[4] Historical Record of the King’s Liverpool

Regiment of Foot; http://oxfordindex.oup.com/view/10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U197827 accessed 12 Feb. 2019

[5] Carlisle

Journal, 4 September 1802, p.1; Carlisle

Journal, 24 September 1803, 3.

[6]

The

Monthly Magazine, vol. 26 (R.

Philips, 1808), 492.

[7]

Cumbria Archives, PR60, Brampton, St Martin’s Parish Registers, 1663–1993.

[8] F. Jollie, Jollies Cumberland Guide & Directory

(Carlisle: 1811)

[9] Tradesman or

Commercial Magazine, 1, (July–December 1808), (London: Sherwood, Neely and

Jones, 1808), 271.

[10]

London

Gazette, 26 November 1811,

2301.

[11] The London Gazette, 25 February 1826, 437.

[12]

Cumbria Archives Service, Carlisle, PR60/21/13/5/100, 6 April 1819; PR60/21/13/5/124,

8 January 1819; PR60/21/13/6/710 February 1820, Brampton Overseers’ Vouchers,

Sarah Oliver.

[13]

Cumbria Archives Service, Carlisle, DCLP/8/38,

Isaac Bird, Grocer, Brampton, Ledger, 1817-19.

[14]

Cumbria Archives Service, Carlisle, PR60/21/13/5/124; Brampton Overseers’

Voucher, Sarah Oliver, 8 January 1819.

[15]

Cumbria Archives Service, Carlisle, DCL P/8/47, Joseph Forster, grocer, Brampton,

ledger, 1819–31; William

Parson and William White, History,

Directory and Gazetteer of Cumberland and Westmorland (Leeds:

Edward Baines and Son, 1829), 426.

[16]

Carlisle Patriot, 30 August 1823 and 3 December 1825.

[17] J. Pigot and Co., National

Commercial Directory [Part 1: Cheshire – Northumberland] for 1828–29

(London and Manchester: J. Pigot and Co., 1828), 71; W. Parson and W. White, History, Directory & Gazetteer of Cumberland & Westmorland,

(Leeds: Edward Baines and Son, 1829), 165

[18]

Carlisle Journal, 1 November 1834, 3.

[19] Carlisle

Patriot, 27 October 1832, 3.