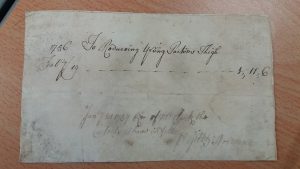

Document Ref D5/A/PO/7 seen in Stafford Record Office is a book (think of a largish School exercise book) recording weekly and extra payments over the years 1813 and 1814 for the Parish of Dilhorne, Staffordshire. Unfortunately the first page is missing. What stood out immediately was the number of payments to members of the Inskip family totaling 32 over the 2 years span.

Of the 32 entries 25 of them appear to be relating to Richard Inskip, his wife or family.

Studying them further the conclusion is that they relate to more than one Richard Inskip as one records paying Richard Inskip for his horse and cart taking Sherratt’s family back. Two entries mention that they paid 4 shillings and 3 shillings to the wife of Richard Inskip Stone Mason. Probably as a Stone Mason he had a horse and cart and Richard Inskip 1763 – 1840 Wheelwright in his Will left a Blacksmith’s shop, house and a piece of land.

This leaves other payments to Richard Inskip’s wife and family totalling £20 4s 0d. This was a large amount of money https://www.measuringworth.com calculates it could be as high as £84,000 in 2018 value.

It was rather complicated trying to find out who Richard Inskip was as Richard was a popular name in the Inskip Family. In the end it required traveling back 5 generations to Richard Inskip a Blacksmith living in Blythe Bridge, parish of Dilhorne (which is next to Forsbrook) and his descendants. Most of these were straight forward as they had a Blacksmith’s shop in Forsbrook, parish of Dilhorne and also a Wheelwright’s. These descendants account for the odd payments to Richard (stone mason) Thomas and Ralph.

The payment on 16 Oct 1813 for “expences at Lane End, Mr Smith, Mr Smalie and John Whalley with Mary Inskip” is more problematic as I could not find any Mary Inskip other than Mary Ridge who married Richard Inskip on 21 Sept 1802 in Dilhorne. The problem was that I had one too few Richards as the ones I had found were married to other wives who were still alive in 1813 and 1814.

Researching for a Richard Inskip born before 1785 (ie old enough to marry in 1802) brought up a man who was transported in 1833/34 and was worth considering.

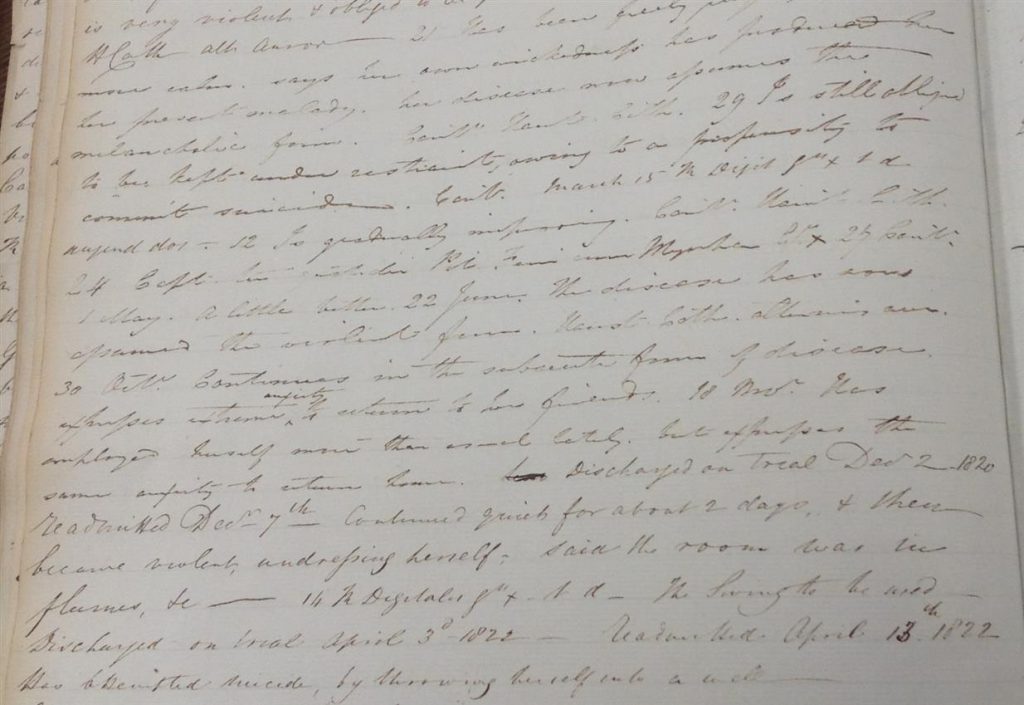

Registers of convicts in the hulk ‘Cumberland’, moored at Chatham, with gaoler’s reports, 1830-1833

“Richard Inskip aged 56 for stealing a quantity of cord. Convicted 28 Feb 1833 at Stafford. Of Bad character disposition and ordours? An old offender (595, 597.) Lifetime in Prison convicted of uttering base coins. V.D.L. [Van Dieman’s Land?] per Moffatt [A Ship] 26 Nov 1833. Born Lane End, Black Hair, Heavy Eyes, Black Lashes. Short oval visage. Can read and write. 5 foot 7½ inches tall. Married with children. Pitted with Small Pox, high cheek bones. Severely scarred on left side. Wife lives by the side of Edward Onions & Wm Field? Under Mrs Batkins, Lane End, Staffordshire”

Registers of convicts in the hulk ‘Dolphin’, moored at Chatham, with gaoler’s reports, 1829-1835 Is similar to the above but adds that he is sentenced to 7 years and he has 7 children

New South Wales And Tasmania: Settlers And Convicts 1787-1859 Richard Inskip assd. To Dr. Desailly

https://www.digitalpanopticon says he was freed in 1840.

The Hobart Town Courier and Van Diemen’s Land Gazette 24 Jan 1840 THE GAZETTE. FRIDAY MORNING JANUARY 24, 1840. GOVERNMENT NOTICE, No. 11, Colonial Secretary’s Office, January 21. The period for which the under-mentioned persons were transported, expiring at the date placed after their respective names, certificates of their freedom may be obtained then, or at any subsequent period, upon application at the Muster Master’s Office, Hobart Town, or at that of a Police Magistrate in the interior: The list includes – Richard Inskip 28 Feb. [1840]

In 1812 /1813 Richard Inskip was accused of Felony. Lane End 27 May 1813. Richard Inskip was accused of stealing a horse. Reading the depositions of witnesses in Stafford Record Office (ref. Q/SB 1813 T/204-206) we learn that on the night of 4-5 June 1812 Thomas More of Penkhull and Robert Jones of Rhuabon lost a 4 year old Dark brown horse 15 hands high with white hind legs a blaze on the forehead and a brown muzzle. No more was heard of the horse until the following August when acting on information they found him “working another team in Cresser” [possibly Creswell].

The horse was stolen around the time of Rugeley Fair in June 1812. Several people saw Richard Inskip with the horse in his stable in Forsbrook. Richard Inskip associated with Wm. Roberts who told George Hurst he was William Smith. They were seen together at the Golden Lion at Lane End.[Now Longton]

27 May 1813 Richard Inskip’s evidence was that he left Rugeley about 4.0pm on 6th June with 4 men. He says he bought the horse for £14? 15s. He had left her with Copestick at Stallington and then fetched her and put her in his stable at Stone house, Forsbrook.

Joseph Copestick of Stallington says on 8th Richard Inskip brought a horse to him asking that it be laid in his land. Richard Inskip fetched the horse on the 28th and paid 20s for the said lay.

Joseph Gosling says that Robert Jones and Thomas More came and claimed the horse on his father’s farm and he took them to Richard Inskip of Forsbrook who had visited the horse in his father’s stable. Richard Inskip said it was his horse that he had bought on the 7th June when returning from Rugeley Fair. It was a stranger who sold it to him. It was suggested that they all go to the Wheat Sheaf at Stoke and send for the Farmer who was said to be present at the time. Richard Inskip ran away towards the place they got the horse from. The examinant ran after but could not catch him.

Hugh Davies, collier, says he was told by Ann Smith of Hanley that Richard Jones of Hanley collier, advanced William Roberts thirty shillings upon a watch which was left in pawn to him, to be redeemed when Inskip and Roberts sold a horse. The watch was not redeemed

Joseph Heath a Blacksmith in Forsbrook said that Richard Inskip bought the brown horse at Rugeley Fair last June 1812 and Richard Inskip asked him [Joseph Heath] to cut 2-3 inches off the tail. He had not been cut before.

Ruth Neath says she has known Richard Inskip for near 2 years and has seen him with William Roberts who has stayed in his house.

Thomas Smith of Forsbrook said he had expected to meet Richard Inskip at Rugeley Fair on 5th June but did not see him. He saw him the next day and asked why he had not come and Richard Inskip gave some excuse he could not remember.

Case sent to the Assizes.

Staffordshire Summer Assizes 1821 Richard, Inskip for Uttering counterfeit money, at Cheddleton—6 Months and sureties for 12. (John Mare admitted evidence.)

The Quarter sessions case of 1813 and its connection to Lane End or as it became Longton and Forsbrook suggested a connection to the payment on 16 Oct 1813.

There was no baptism for a Richard Inskip in Dilhorne or Longton / Lane End but there was one in St. Peter Ad Vincula, Stoke on Trent on 27 Aug 1767 and he was the son of Edward and Mary Inskip. There was at least one older sister for Richard baptised at St. Peter’s and this was Hannah baptised 12 July 1761 the daughter of Edward and Jane Inscip of Lane End.

Edward was not such a common name in the Inskip family and his baptism was found back in Dilhorne on 12 Feb 1727 and he was the son of Thomas and Sarah Inskip who may have married in 1723 at St Alkmund’s, Derby, Derbyshire. Thomas died 1737.

There is a problem with the Dilhorne Parish Records. Thomas must have been born before 1705 to have married in 1723 and there is something of a gap in the Parish Records. Browsing the Parish Register there are retrospective entries by either the new Vicar or Parish Clerk of items found after the previous Vicar had died. Unfortunately Thomas Inskip is not included but there only appears to be one couple baptising children at the time so Thomas was probably the son of Richard Inskip, Blacksmith 1662-1708.

This gives a connection between the Inskips of Longton / Lane End and Dilhorne. If Richard and Mary married in All Saints Dilhorne and baptised children there it suggests that they may have been living there for some time.

They appear to have had the following children

- George Ridge Inskip baptised 1803 in Stone, Staffordshire died 1815

- Ralph Inskip baptised 1805 in Dilhorne

- John Inskip born about 1808 in Dilhorne [name supplied by Inskip one name study]

- ??????

- James Inskip baptised 1815 in Longton

- Mary Inskip baptised 1816 in Longton

- George Inskip baptised 1818 in Longton

- Eliza Inskip baptised 1821 in Longton

- Joseph Inskip baptised 1825 in Longton.

The youngest child, Joseph, was baptised at the New Connextion Chapel, Longton which records “Joseph Inskip born 3 Nov 1825 and baptised 4 Dec 1825 the 9th child of Richard Inskip, Labourer of Lane End by Mary daughter of William Ridge, Potter of Lane End.”

The Dilhorne Overseers may have been supporting Richard’s wife Mary and his children until they managed to get them back to Longton.

The 1841 Census HO107/991 folio 6 shows Mary Inskip aged 60 living in Willow Street, Longton with her son Joseph aged 15 a collier and her son George appears to be married and living a few doors away.

Staffordshirebmd.org.uk has a death entry for Mary Inskip aged 75 registered in Burslem. No death certificate has been bought but Mary’s son John is living in Haywood Pl, Burslem in 1851 working as a Potters Fireman.

No death has been found for Richard Inskip but he was still alive in 1845 when the Hobart Town Courier and Van Diemen’s Land Gazette reported on Sat 1 Feb 1845 “Case against Richard Inskip was dismissed. Inskip had challenged Turner to fight, and got the worst of it”