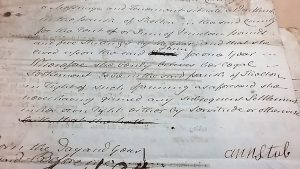

Figure 1: PR5/43, Greystoke Poor Account Book, 1740-1812

When Grace Sandwick was granted poor relief by the parish of Greystoke and boarded out with Deborah Bushby in 1774, she brought with her a range of clothing and belongings. Apart from what is recorded in Greystoke’s Poor Account, nothing further has yet come to light to provide further information on Sandwick. Deborah Bushby was baptised in Greystoke on 13 April 1738 and buried in the parish church on 29 January 1814.

The parish recorded in its Poor Account Sandwick’s possessions. Sometimes parishes sold such goods to help defray the cost of relief. On other occasions, if the pauper was admitted to a workhouse, the items could be stored and returned should the pauper leave. In this instance, as Sandwick was boarding with Bushby, it looks as though the list was draw up so that there could be no dispute over what Sandwick owned.

April ye 7th 1774 Agreed with Deborah Bushby for Grace Sandwicks Boarding for one year at the rate of four pounds four shillings pr year to be paid quarterly.

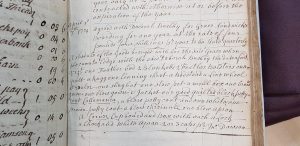

A schedule of the Goods brought with her the said Grace when she came to lodge with the said Deborah Bushby the date afored: viz one feather bed, 2 Blanketts, 2 Feather Bolsters, one quilt, a kuggone[?] lining sheet a Bedstead a line whool [____alor?] one shag hat one stew pot a meal box and brown gown one blew gown & jacket one good quilted black petty coat Callamanca, a blew petty coat and one white one brown petty coat a blew cardinall one blue apron a corner cupboard and Box each with a lock a Check and White Apron 2 or 3 caps.

Though poor, Sandwick had a change of clothes. Some of the terms used to describe them are unfamiliar to us today but they tell us about something the quality and durability of what she wore. From the seventeenth century ‘shagg’ was used to describe the nap of cloth. It was often coarse and long. Sometimes it was used to describe worsted cloth having a velvet nap. Such material was often used for linings. Calamanco was an unprinted, plain cotton, often white. The ‘blew cardinal’ was a short cloak with a hood.

The lockable cupboard and box were important as a means of securing possessions, particularly when spaces were shared. For many people in the eighteenth century, a lockable box was the only private storage facility they had. Lockable boxes became associated with servants. They could be used to transport belongings between one job and the next. The lack of a box, as Amanda Vickery points out was ‘a sign of the meanest status’.

Sources

CAS, PR5/43, Greystoke Poor Account Book, 1740-1812.

National Burial Index for England and Wales, St Andrew, Greystoke, 29 January 1814.

Amanda Vickery, Behind Closed Doors: At Home in Georgian England (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), pp. 38-40.