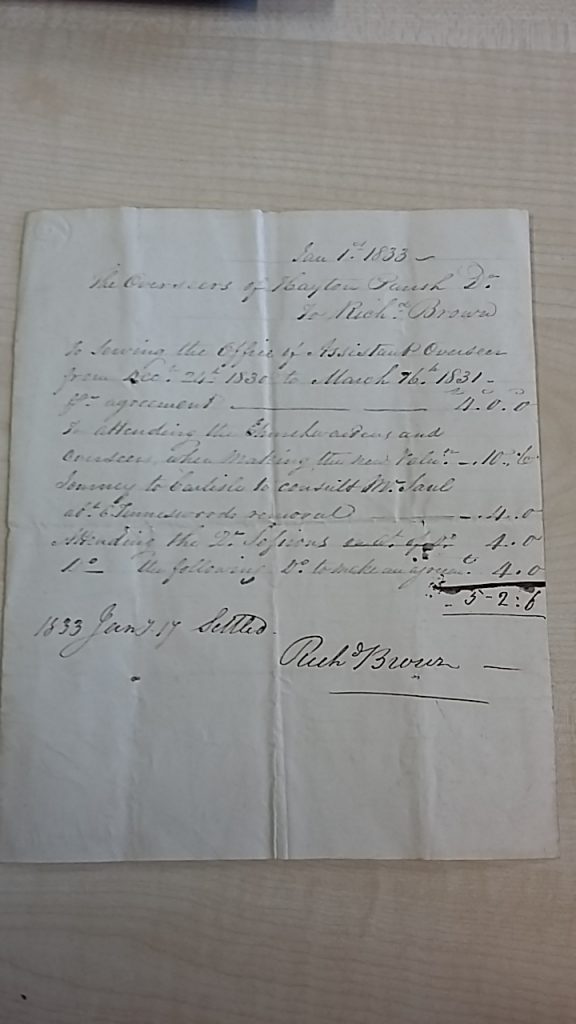

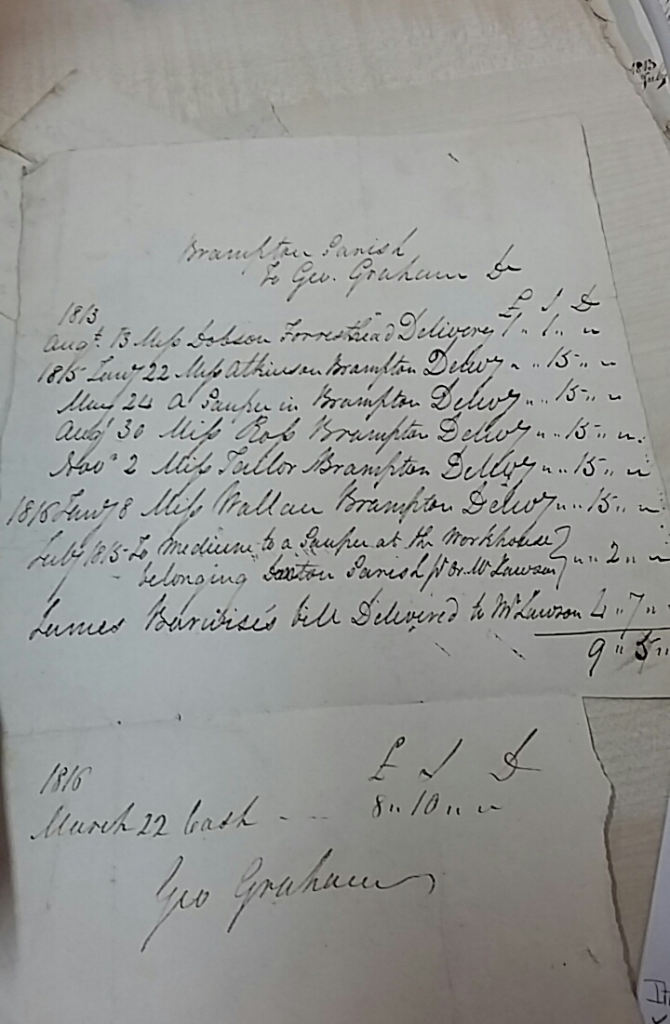

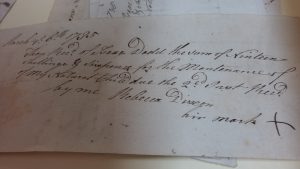

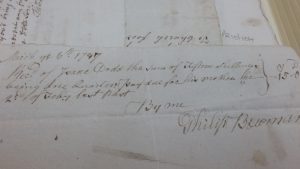

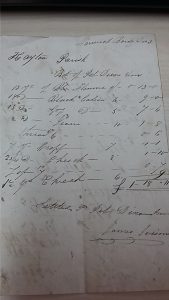

Parish vestries utilized printed documents and books to record the business they carried out. These were supplied by stationers including Charles Thurnam.

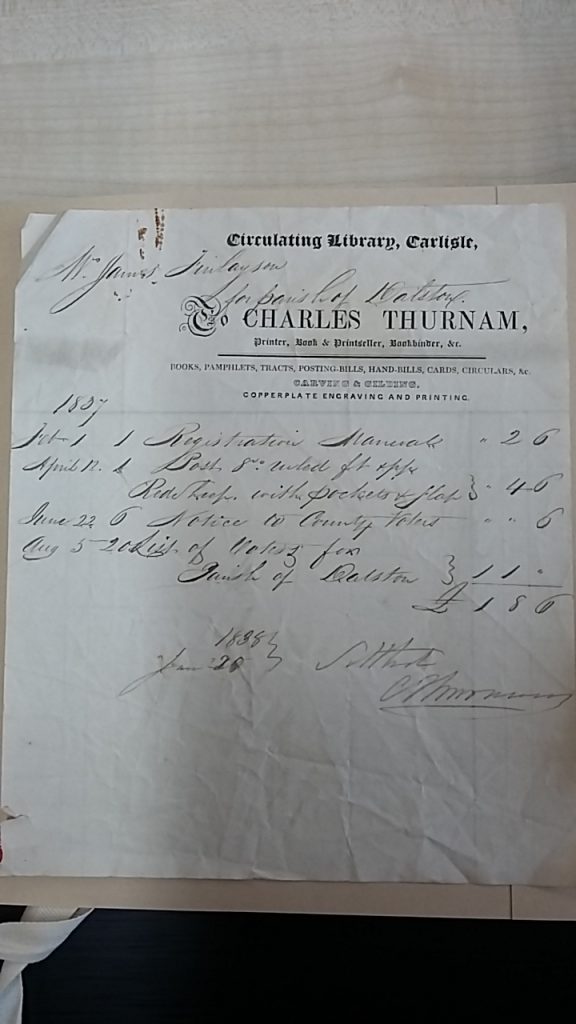

There is evidence that Thurnam supplied Dalston Parish with Registration Manuals at 2s. 6d, and Notices for County Voters 6d. [1] He also supplied memo books 2s 6d. [2] From 1820 onwards, he supplied Hayton parish with Apprentice Indenture forms. [3] Local business were supplied with cash account books.[4] He directed some of his advertising at Parish Councils in the following manner:-

To Magistrates, Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor This day is published price 9d per pair the new form of Orders and Indentures for binding parish Apprentices. [5]

and

To the members of the Select Vestries, Parish Overseers &c. Just published 12s A Summary of the Law of Settlement by Sir Gregory Lewin also by the same auther price 14s a Treatise on the maintenance of the poor’. [6]

Charles Hutchinson Thurnam was born on 15 April 1796 in Edinburgh. He was the youngest of three brothers. His father Timothy Thurnam (c.1770- 1798) a surgeon married Dorothy Graham (b1768) at Grey Friars, Edinburgh, on 11 January 1819. Her father William Graham was also a surgeon and apothecary who had married Dorothy Brisco in 1762. He died in Carlisle in October 1782 aged 45.[7] Charles Thurnam’s brother Timothy became a surgeon in the Army. In 1798 when Timothy was 28 he died when the ship carrying him to India sank. At some point after this, Charles along with his two brothers William Graham Thurnam (b.1792) and John Dodsworth Thurnam (b.1794) moved to Dalston, a village 4 miles from the city of Carlisle. Their mother may have been with them, however, a death did occur of a Dorothy Graham married to T. Thurnam in St Cuthbert’s Parish, Edinburgh, in 1799. [8 ] This Dorothy Graham might be the mother of the three Thurnam boys.

Charles was to see both his brothers die at a young age. William joined the army in 1807 and died from wounds received at Doola (Doolia) near Malligaum, India, while serving in the army of the East India Company on March 14 1823 aged 31.[9] John Dodsworth died as a result of illness on 20 May 1829 aged 26. [10]

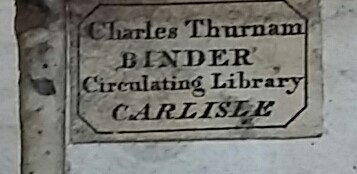

Charles moved to Carlisle and began his stationary business at 5 English Street in 1816, selling books and journals as well as patent medicines.[11]. It was common at the time for booksellers to sell medicines. A year later he established a subscription circulating library lending ‘best sellers’ and other popular works that reflected public demand. Probably beyond the reach of the poor, it was particularly popular with middle-ranking women, although some raised concerns about the effect the books would have on their morals and manners.[12]

On 11 January 1819 Charles married Ann Graham (1800-1857) daughter of John Graham, surgeon, in Carlisle. While they went on to have a large family, many of their children died at a relatively young age. William and Harriet as infants , Mary Elizabeth (1840-1843) aged 3, and Charles (1821-1840) aged 19.[13]. Margaret Dorothea (1819-1879), Isabel (1829-1878) and Ann Harriet (1834-1917) remained unmarried and compared with others in the family lived to a good age. Ann Harriet ran part of the stationery business that had expanded into music. Her sister Katherine (1826-1875) married Henry Edmund Ford (1821-1909) organist at Carlisle Cathedral who also was involved with the music side of the business.[14]

Charles expanded the business by becoming an insurance agent. Charles’ own life insurance helped pay off mortgages after his death. [15] The Circulating Library continued to grow. By 1827 it had 1000 books on its list, and continued in exostence until the 1950s.[16]

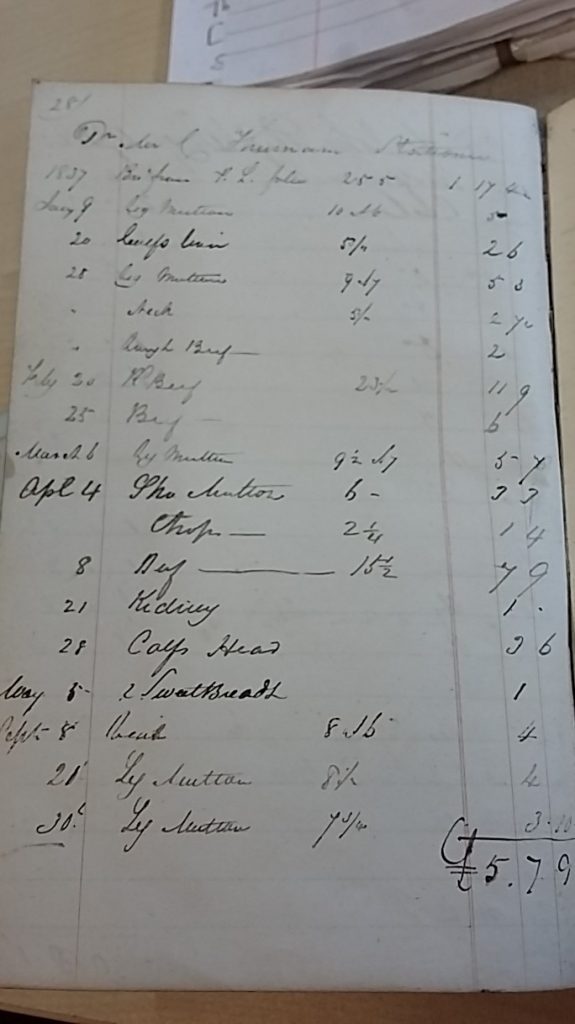

Other traders in the city benefitted from Charles’ patronage. An account with a city butcher to whom he supplied a cash book, shows some of the items he bought in April 1837, beef 7s 9d, kidney 1s, a calf’s head 3s, as well as a lot of mutton.[17] The bill for 1837 totalled £5.7s.9d. John Robson, a chemist, also provided him with supplies: 2 oz Olives and 1 oz Cinnamon in September 1832 as well as turpentine, glue, vinegar and six books of gold leaf.[18 ]

Charles seems to have been driven to succeed being regularly seen in English Street collecting parcels in the early hours from the coaches that ran between Edinburgh, Carlisle and London. In August 1835 the Proprietors of the Carlisle Patriot asked Charles to take over the printing of the newspaper from the old Patriot Office. This became inconvenient for Charles and soon afterwards he removed the presses and other materials to his own premises. On the 16 August 1836 a meeting of the newspaper proprietors was called at the Bush Inn, Carlisle. An order was issued to return the press which belonged to the Patriot Committee. An altercation followed this meeting between Charles and Dr John James. At some point Dr James sustained some injuries and issued a writ for assault against Charles Thurnam 29 August 1836. There were no witnesses to give evidence as to the cause of his injuries although William Nicholson Hodgson, pawnbroker, gave evidence at the Christmas Sessions 1837 to the effect that he heard the ‘scuffle’. [19] The matter seems to have been resolved and Thurnam’s business prospered.

After Charles’ death on 28 April 1852, the business was taken over by his widow Ann and trustees (their sons William Graham (1836-1859) and James Graham (1837-1872) were under 21).[20] Charles left annuities to his daughters in his will including his second eldest daughter Anna Maria Brisco (1822-1872) who married Josiah Foster Fairbank (1821-1899) in 1854 and moved to Scarborough. The same year family history repeated itself on 29 June another son Dodsworth John (1828-1854) died at sea. With the death of their mother Ann on 31 January 1857, the business continued in the hands of William Graham and his brother James Graham.[21]

In 1859 William had become ill and, seeking to improve his health, he went to Rome but died whilst there on 8 August.[22] With the death of James Graham in 1872 the ownership of Charles Thurnam and Sons by a member of the family ceased. Later owners continued to trade under the Thurnam name. The name Thurnam perhaps now having a proven brand recognised in the city.

Charles and Ann Thurnam had one more son, George (1825-1868). He was never mentioned in his parents wills although he did start working with his father. After 1841 he appears to have moved away from Carlisle. An engraver by trade first marrying Mary Ann Mayne in Lambeth, London, on 14 June 1846 then after her death Margaretta Long in Hammersmith, London, on 4 January 1863.[23] Both Isabel and Margaret Dorothea left a legacy of £100 each to his children George Charles Thurnam and James Edward Thurnam. [24]

Margaret Dorothea and her sisters Ann and Isabel had shares in properties at Brownelson and Lingyclose Head near Dalston and properties once occupied by Thurnams and Sons at English Street, Kings Arms Lane and Peascod Lane, Carlisle. In 1916 Ann lived at 22 Hartington Place, Carlisle, which had been purchased by Margaret Dorothea. Margaret Dorothea and Isabel left shares of their estates not only to each other but to their named nephews and nieces. Margaret Dorothea also left legacies to various charities and the Cumberland Infirmary in Carlisle.

This is a work in progress subject to change with ongoing research.

.

Sources

[1] Cumbria Archives SPC44/2/47/16 Dalston Overseer Voucher 1 February 1837-20 January 1838; SPC44/2/48 no line number Dalston Overseers Voucher April 13- May 21 1831.

[2] Cumbria Archives, SPC44/2/48 no line number Dalston Overseers Voucher April 13- May 21 1831

[3] Cumbria Archives, PR102/126 Apprenticeship Indentures ,1783-1833, St Mary Magdalene, Hayton (Charles Thurnam (1820 onwards).

[4] Cumbria Archives DCL P/8/55 Butcher (T Mitchell?) meat sold book 1836-1837.

[5] Carlisle Patriot, 2 August 1817.

[6] Carlisle Journal, 25 April 1829.

[7] www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk accessed 8 July 2019. Cumbria Archives St Cuthbert’s Monumental Inscriptions

[8] www.scotlandspeople.cov.uk accessed 8 July 2019.

[9] www.Books.google.co.uk Alphabetical List of Officers of the Indian Army 1760-1834 Bombay Presidency, Edward Dodwell. Accessed 7 July 2019.

[10] Headstone at St Cuthbert’s Church, Carlisle, Cumbria 1 July 2019.

[11] Cumberland News 4 November, 1916, p. 5.

[12] Carlisle Patriot, 5 April 1817

[13] Carlisle Journal, 3 June 1843

[14] Cumberland News, 5 July 1991

[15] J. Pigot and Co. National Commercial Directory Cumberland & Westmorland and Lancashire Pigot Directory 1829 (London and Manchester, 1828), Charles Thurnam, English Street, Carlisle.

[16]Carlisle Patriot 10 March 1827

[17] see 4

[18] Cumbria Archives, DB 138/1 Accounts John Robson Chemist 3 Account Books goods bought by named customers, 1834-1845.

[19] Cumbria Archives, DHOD/13/153 Papers Assault, Dr James Surgeon of Carlisle.

[20] Carlisle Patriot, 1 May 1852.

[21] Cumbria Archives DRC/22/95, J. Wilson. 1890 The Monumental Inscriptions of the church Churchyard and Cemetery of St Michael’s Dalston W Beck (1890).

[22] Carlisle Journal, 20 May 1859.

[23] www.ancestry.co.uk accessed, 1 July 2019.

[24] Cumbria Archives, PROB 1879/W880, Will of Margaret Dorothea Thurnam, 1879.

Footnote

Charles Thurnam and Ann Graham were buried at St Michael’s Church Dalston Cumbria Archives (Dalston Monumental Inscription of the church of St Michael 1890)

When Thurnam and Son’s celebrated its 100th anniversary. It was reported she was the last survivor of the family along with her nephew Dr William Rowland Thurnam (1868-1941) son of James Graham Thurnam and Elizabeth Irving. A survivor of Tuberculosis he specialised in it’s treatment Others were found while researching this blog amongst hem Edmund Brisco Ford (1901-1998) an Ecological Geneticist, Grandson of Henry E Ford and Katherine Thurnam as well as the descendents of Josiah Fairbanks and Anna Maria Brisco Thurnam.