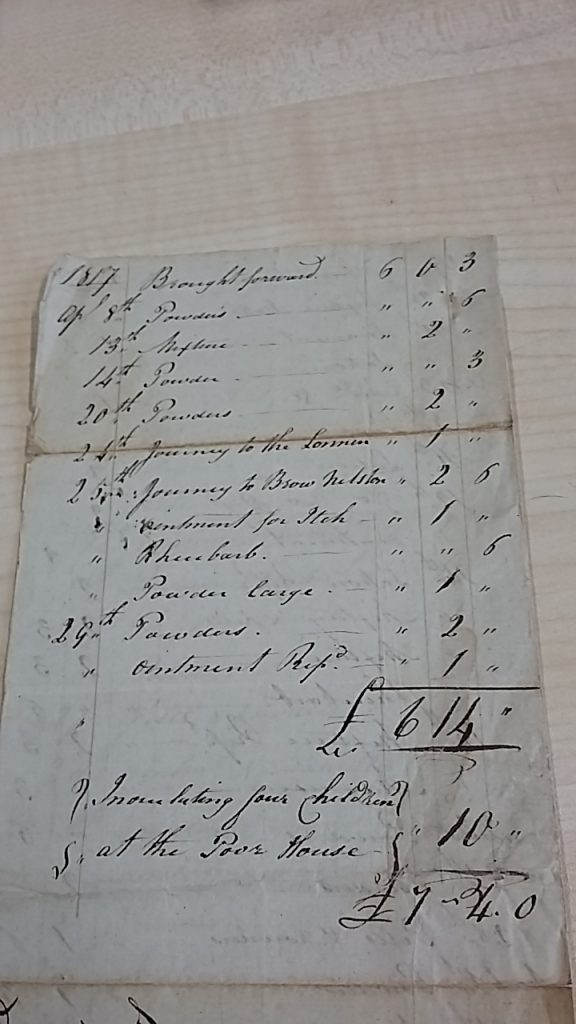

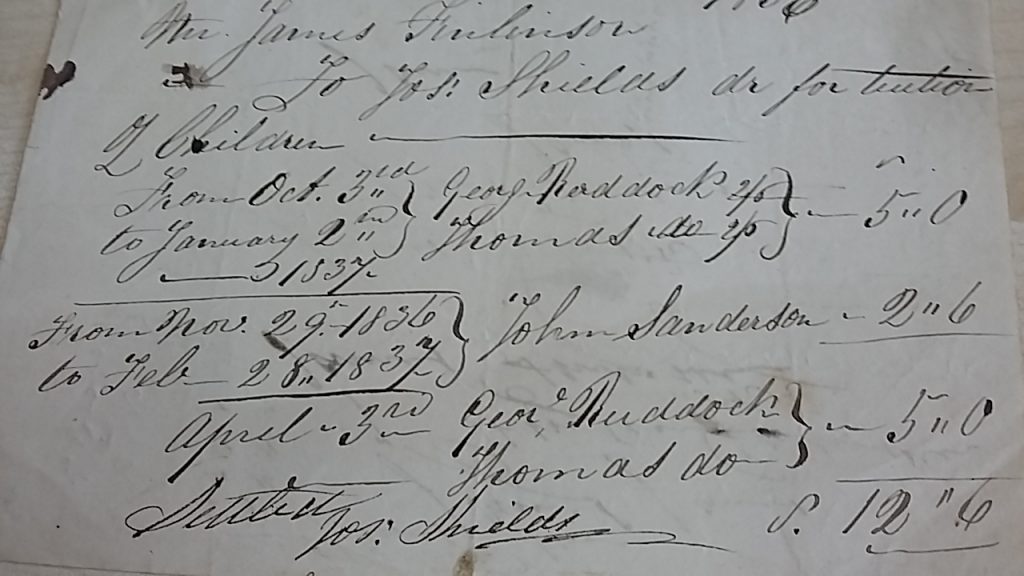

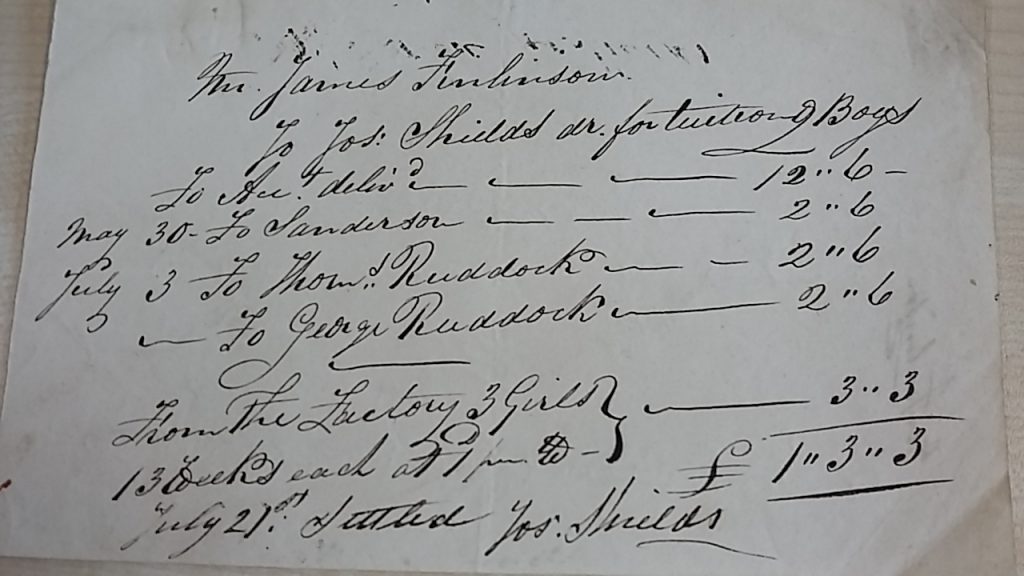

Looking for evidence of who the pupils were who attended Joseph Shields identifies the following:

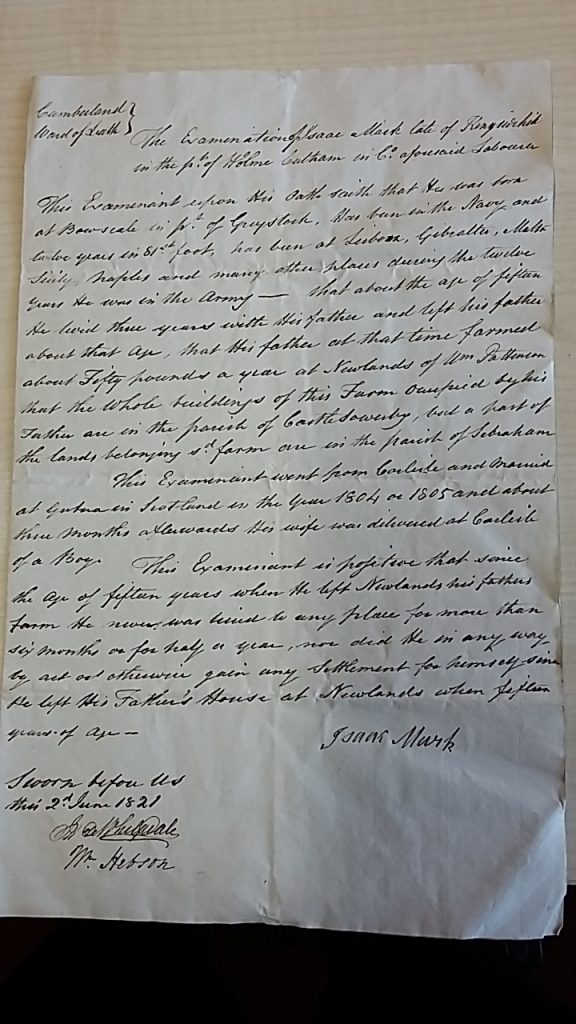

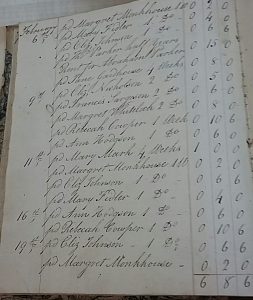

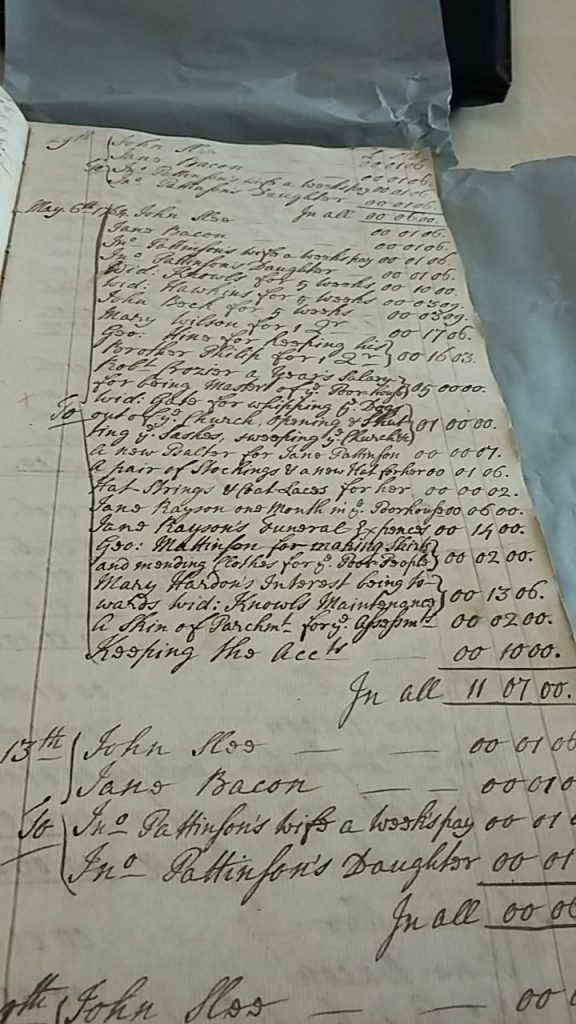

John Sanderson was the son of Ruth Sanderson. She was listed as a single woman of Hawkesdale Poorhouse when he was baptised on 29 April 1827. His father was named as Joseph Bowman of Kiitchin Hill ,Torpenhow, husbandman, who was pursued for contributions towards his son’s maintenance.[1] Ruthe Sanderson was described as being in the poorhouse when John’s older brother, Joseph, was baptised on 12 January 1817 and his sister Sarah on January 28 1821.[2] Ruth Sanderson received payments under her status as the mother of illegitimate children from Dalston Parish between April 1824 to April 1831. Initially this was 2s weekly, then reduced to 1s 6d weekly. [3]

John Sanderson appears to have worked in the cotton weaving industry in Dalston and then in Caldewgate, Carlisle living with his sister Sarah and mother until around the time of her death in 1867. At the time of the 1871 census he was one of the labourers building the Lindley Wood Reservoir near Harrogate, Yorkshire.[4]

The brothers George (15 December 1831) and Thomas (6 June 1831) were the children of George and Jane Bell. George the elder was a miller of New Village, Dalston.[5]

The Roddick family, which also included sisters Ann and Elizabeth, was receiving outdoor relief of 4s weekly from 21 March 1830 to December 1835. [6]

Thomas Roddick married Agnes Cookson 7 September 1850 at Gretna signing his name while Agnes made her mark. On leaving Dalston, they settled near by in Cummersdale. Thomas was working in a textile mill .

By 1850 George Roddick hadbeen convicted twice for theft. The first occasion was on 10 November 1849. Along with John Dixon, he stole an axe belonging to Mr Thurnam selling it on to a James Hamilton in Carlisle. Charged under the Juvenile Offenders Act, they received a three week prison sentence. [7] At the Michaelmas Quarter sessions of 1850 George was given a six month jail sentence with hard labour and one month’s solitary confinement for breaking in and stealing glasses, porter, lemonade and other items from the tent of Mrs Robinson on the night of the Carlisle Fair on 19 September. His accomplice, Joseph Armstrong was described as of ‘imperfect instruction’, while George was described as ‘a labourer aged 21 who is well instructed’. [8]

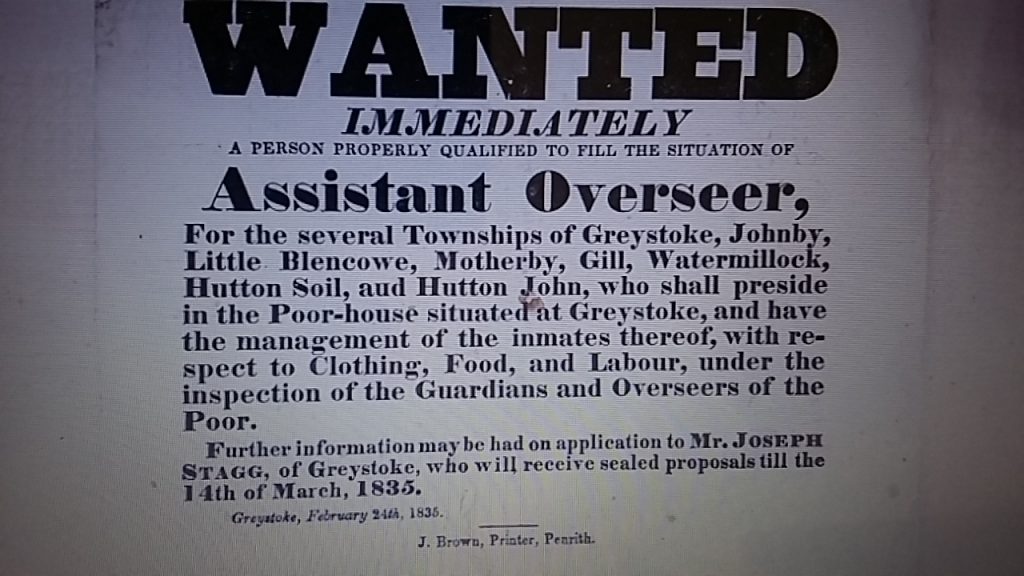

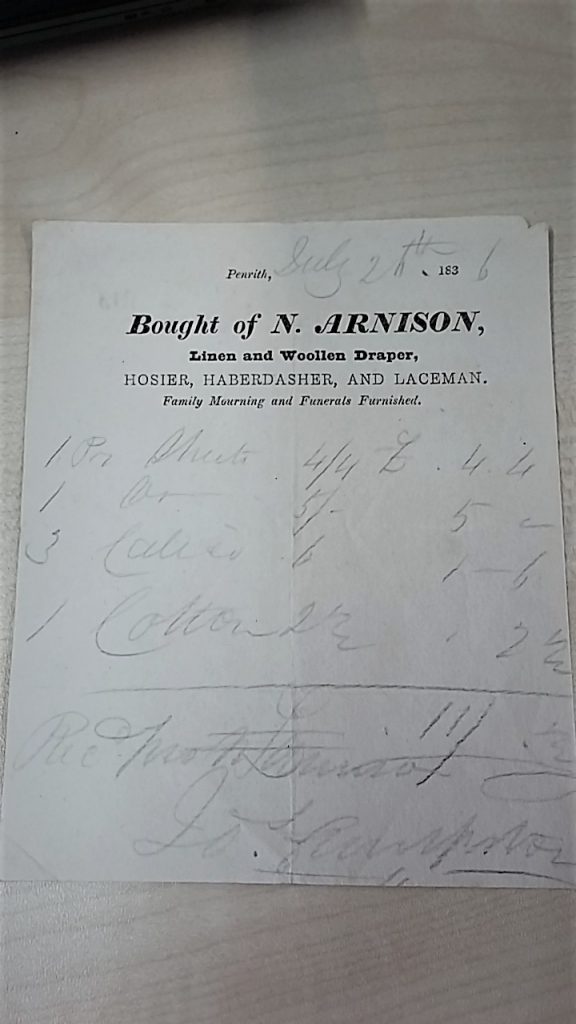

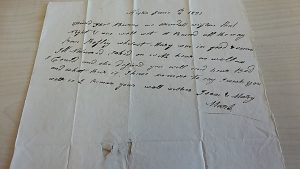

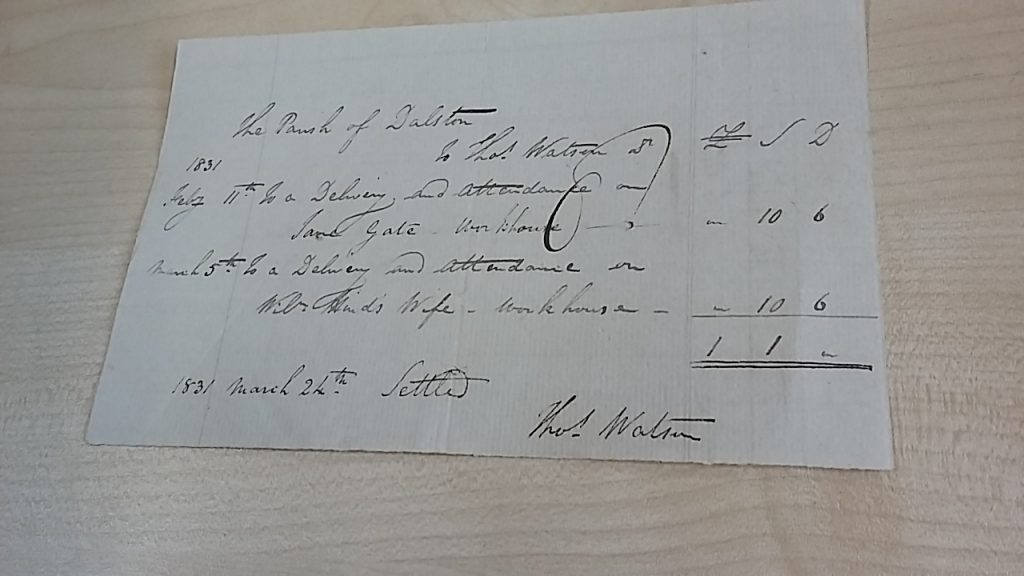

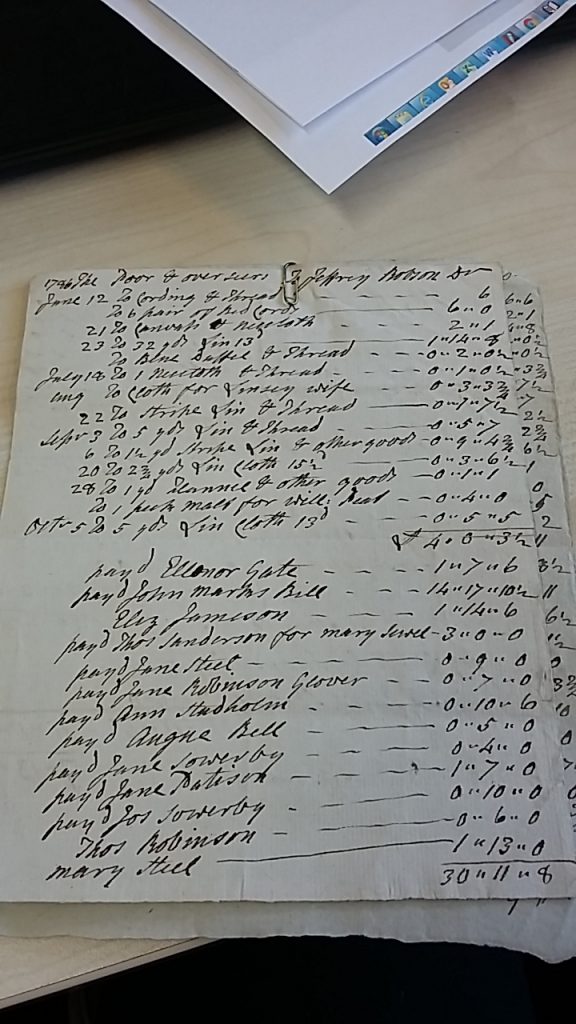

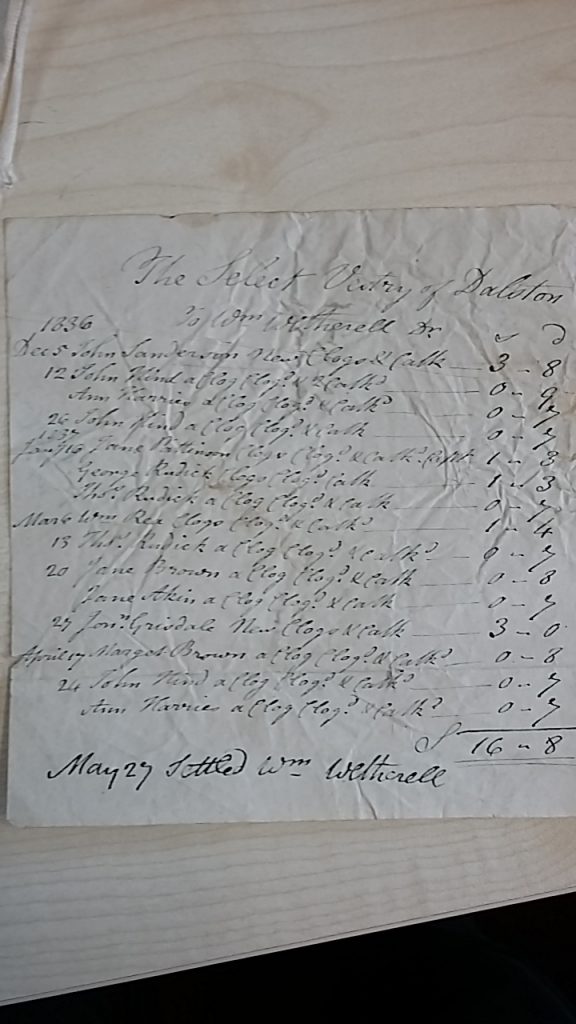

John Hind cannot be positively identified, as is the case with the three girls. It is possible the girls are some of those who appear on a bill from William Wetherall for repairing clogs and making new ones. The boys’ names appear on his bill. [9] The girls may have worked in one of the textile mills situated in Dalston. The voucher for the girls is dated after the Factory Act 1833 where children from the textile mills had to attend school six times a week for two hour sessions. They also needed a schoolmaster’s certificate in order to be employed the following week [10]

[1] Cumbria Archives, CQ5/8, Bastardly Bonds, Easter 1827

[2] Cumbria Archives, PR 41/8, Dalston Parish Register, Baptisms 1813-1832;

[3] Cumbria Archives, SPC 44/2/35, Account book for the maintenance of Illegitimate children, 1833-1836

[4] ancestry.co.uk [accessed 19 September 2019]

[5] Cumbria Archives, PR 41/8, Dalston Parish Register, Baptisms 1813-1832;

[6] Cumbria Archives, SPC 44/2/32 1826-1840, Account Book for weekly outdoor relief.

[7] Carlisle Patriot, 10 November 1849

[8] Carlisle Patriot, 19 October 1850

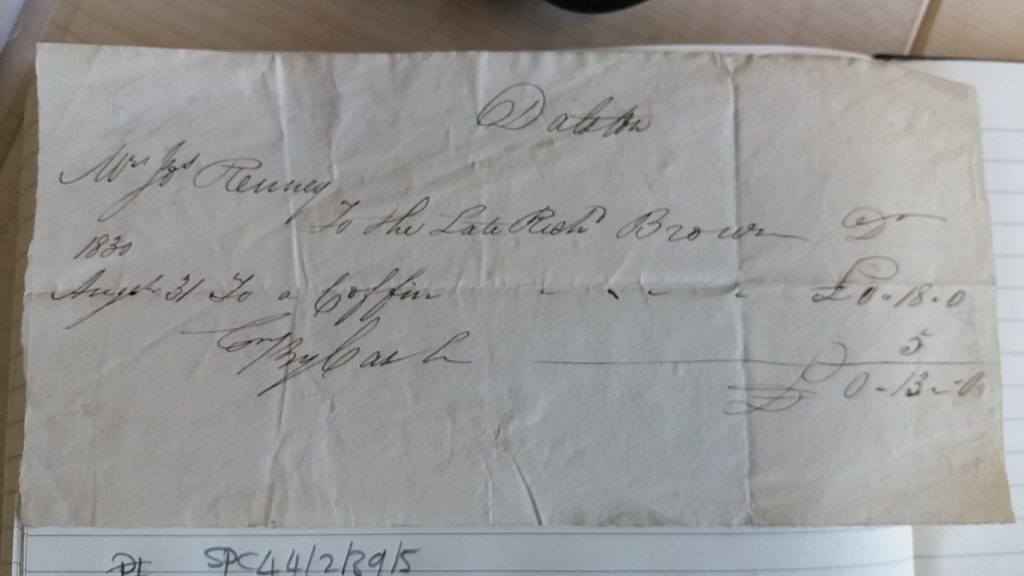

[9]Cumbria Archives. SPC44/2/43/13 Dalston Overseer Voucher 1836=1837

[10]Platt, Jane, Making their Mark (Amadeus Press, 2019)