Uttoxeter has a long tradition of cheese-making. By the mid-seventeenth century it was already established as a major centre of the trade in the Midlands, and in the 1690s there were weekly cheese markets and extensive storage facilities. These were used by Uttoxeter’s cheese factors who were engaged as agents by London cheesemongers. By the mid-eighteenth century Uttoxeter’s importance as a centre for cheese meant that some agents retained by London merchants spent more than £500 in a single day on butter and cheese.

Pigot’s directory of 1828–9 notes that ‘the trade in cheese is also of some consequence’ and lists Thomas Earp, James Lassetter, and Orton and Arnold as cheese factors alongside maw dealers Edward Gent, James Stringer, John Vernon and Co., and Henry Wigley. Before the commercial availability of rennet, curdling milk for cheese involved drying and salting a calf’s stomach or maw, and then soaking pieces of it in water. The resulting liquid was added to milk to create the curd.

Supplementing the weekly cheese markets, White’s 1834 directory notes that Uttoxeter held three cheese fairs a year in March, September and November and was known for its ‘considerable trade’ in ‘preparing calves maws, to be used in curdling milk’ for cheese. Under the heading of ‘Cheese Factors & Hop & Seed merchants’ the directory lists Thomas Earp, James Lassetter, and Orton and Arnold. Ellen Gent, James Stringer, John Vernon and Co., Elizabeth Wigley, and Frederick Wigley were cheese skin makers. In 1834 William West noted that Uttoxeter was ‘remarkable for instances of longevity of its inhabitants’ and for its ‘abundant supply of cheese, butter, hogs, corn and all kinds of provisions’. Perhaps the latter was the cause of the former.

Workhouses served their inmates with food and drink according to what were known as dietaries, or daily allowances, which stipulated provision across a week. If these are taken at face value, cheese formed a considerable part of the diets of the poor. Tomkins notes, however, that dietaries should be regarded as statements of intent rather than actual evidence of practice and need to be corroborated by other sources. Until a shortage of bread and flour in the 1790s, at St Mary’s Workhouse, Lichfield, the 41 inmates (making it directly comparable in size to Uttoxeter workhouse) were served puddings, and bread and cheese dinners three times a week. With the shortages, milk pottage was served up for breakfast. Dinner on Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays consisted of meat and vegetables; alternating with Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays offerings of broth and cold meat. On Saturdays inmates were given bread and cheese.

In the 1820s the overseers of Uttoxeter purchased large quantities of cheese for the workhouse from a wide range of suppliers including James and John Bamford, Ralph Bagshaw (see separate entry), Thomas Cope, Thomas Earp (see separate entry), Porter and Keates, John Rushton, William Summerland (see separate entry), Edwin and Josh Wibberley, and Sir T. Sheppard, bart. Amounts varied from the 120lb supplied by Mr Bamford in May 1821, through the 90lbs supplied by William Summerland in May 1825, to the 13.5lbs supplied by Ralph Bagshaw in September 1827.

By the 1830s, just as in the 1820s, cheese came from no single supplier. In September 1830 William Bennett supplied over 2cwt of cheese costing £5 10s 4d. Thomas Earp’s bill for cheese in March 1831 amounted to £4 9s 1d. Fifty-five cheeses weighing 4cwt were supplied by Thomas Gell at a cost of £12 4s 3d in April 1832. The variation in the amounts and the regularity of cheese supplied are probably because the workhouse was producing its own cheese. Between 24 April and 30 June 1830, for example, Thomas Hartshorn supplied the workhouse with 947 quarts of milk. This was far more than the population of 40 or so inmates could readily consume suggesting that the milk was being used to make cheese. Hartshorn also supplied 33 quarts in June 1832, followed by 180 quarts in July. The workhouse also had its own milk cart, a wheel of which was repaired and painted by Thomas Mellor in April 1829.

Sources

Julie Bunting, ‘Bygone Industries of the Peak, Cheese-Making’, The Peak Advertiser, 29 January 1996

Catherine Donnelly, The Oxford Companion to Cheese (Oxford, OUP, 2016), 153–4

London Gazette, part 2 (1836), 1369

Sir Frederick Morton Eden, The State of the Poor, A History of the Labouring Classes in England 3 vols (London: 1797), edited and abridged A. G. L. Rogers London: George Routledge and Sons, 1928), 307.

John E. C. Peters, The Development of Farm Buildings in Western Lowland Staffordshire up to 1800 (Manchester: MUP, 1969), 130

Pigot and Co., National Commercial Directory [Part 2: Nottinghamshire–Yorkshire and North Wales] for 1828–29 (London and Manchester: J. Pigot and Co., 1828), 741–2

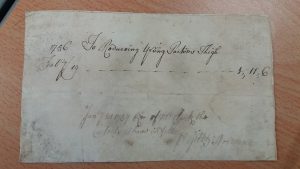

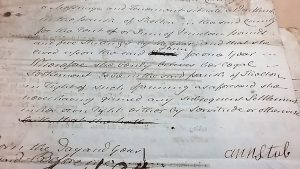

SRO, D3891/6/8, Uttoxeter volume of parish bills, 1821–4

SRO, D3891/6/9, volume of parish bills, 1825–29

SRO, D3891/6/34/1/14, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Thomas Mellor, 3 April 1829

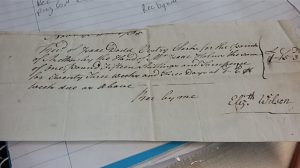

SRO, D3981/6/36/3/4, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, William Bennet, 11 September 1830

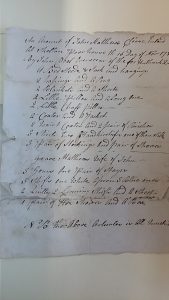

SRO, D3891/6/36/8/11a–d, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Thomas Hartshorn, 31 July 1830

SRO, D3891/6/37/2/7, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Thomas Earp, 26 Mar 1831

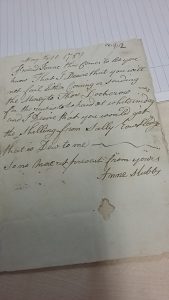

SRO, D3891/6/36/6/66, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Edwin Webberley, 23 December 1831

SRO, D3891/6/37/11/5, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, John Foster, 21 February 1832

SRO, D3891/6/39/2/26, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Thomas Gell, 20 March 1832

SRO, D3891/6/39/5/5, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Thomas Hartshorn, 10 June–15 July 1832

SRO, D3891/6/39/6/3, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, Joseph Durose, 8 November 1832

SRO, D3891/6/40/1/10, Uttoxeter Poor Law Vouchers, R. Keates, [1833?]

Joan Thirsk, Agrarian History of England and Wales, 1640–1750, part 1 (Cambridge: CUP, 1985), 133

H. D. Symonds, The Universal Magazine, vol. 23 (November 1758), 219

William West, Picturesque Views and a Description of Cities, Towns, Castles and Mansions and other Objects of Interesting Feature in Staffordshire from original designs, taken expressly for this work by Frederick Calvert engraved on steel by Mr T. Radclyffe (Birmingham: William Emans, 1834), 96

William White, History, Gazetteer and Directory of the County of Staffordshire and of the City of Lichfield (Sheffield: 1834), 762