Clogs feature in both the Staffordshire and Cumberland vouchers. In 1829 and 1830, for example, the overseer of Uttoxeter Mr Wood paid John Green for the following:

| 2 Sept 1829 | Pair of Clogs | 1s 4d | John Green | Mr Wood |

| 7 Nov 1829 | 1pr clogs | 1s 8d | ||

| 18 Nov 1829 | 1pr of clogs ordered by Mr Wood | 1s 10 | ||

| 21 Nov 1829 | 1pr of clogs ordered by Mr Norres | 1s 6d | ||

| 18 Dec 1829 | 1pr of clogs ordered by Mr Wood | 1s 10d | ||

| 8s 2d |

| 10 Jul 1830 | 4 pr boys clogs | 5s 4d | John Green | Mr Wood |

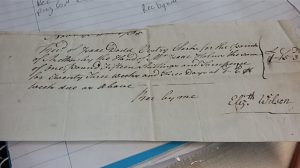

Clogs were also by the overseers of Darlaston, Staffordshire: in 1818 Thomas Challinor was paid for three pairs.

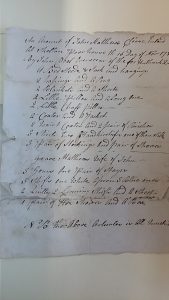

In Skelton, Cumberland, the inventory of Grace Matthews goods and clothes included one pair of clogs. There is a separate blog entry for Matthews.

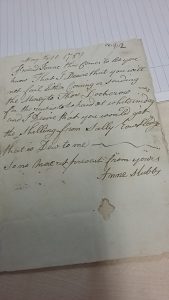

In Wigton, Cumberland, Thomas Watman’s 1773 bill refers to the calking of clogs.

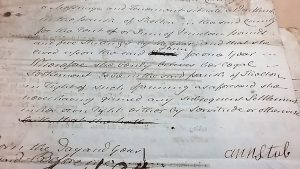

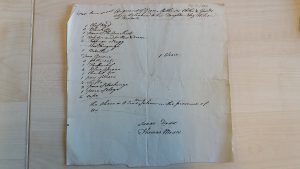

Details of two further vouchers from Wigton (1771) and Skelton 1791 are shown below.

| 6 Dec 1771 | John Barnes John Little |

Daniel Steel Daniel Steel |

John Barnes John Little |

£0-3-8 £0-0-11 |

for 3 pairs of clogs Ironing 3 pairs of clogs |

| 1 Jun 1791 | Thomas Mather | William Stalker | Thomas Mather | £4.19.0 | Maintenance, repair of clogs & 6 mths house rent |

In his State of the Poor Frederick Morton Eden recorded: ‘Some years ago clogs were introduced into the county of Dumfries from Cumberland, and are now very generally used over all that part of the country, in place of coarse and strong shoes. The person who makes them is called a clogger. “All the upper part of the clog, comprehending what is called the upper leather and heel quarters, is of leather, and made after the same manner as those parts of the shoe which go by the same name. The sole is of wood. It is first neatly dressed into a proper form; then, with a knife for the purpose, the inside is dressed off, and hollowed so as to easily receive the foot. Next with a different kind of instrument, a hollow or guttin, is run round the outside of the upper part of the sole, for the reception of the upper leather, which is then nailed with small tacks to the sole and the clog is completed. [The Staffordshire vouchers often contain quantities of ‘tacketts’]. After this they are generally shod, or plated with iron, by a blacksmith. [Calking clogs – adding iron strips or plates to improve their durability – appears on numerous bills for Cumberland]. The price of a pair of men’s clogs (in Dumfrieshire) is about 3s including plating; and, with the size the price diminishes in proportion. A pair of clogs, thus plated, will serve a labouring man one year … at the end of that period, by renewing the sole and plating, they may be repaired so as to serve a year longer… [Many of the Cumberland bills are for making such repairs]. They keep the feet remarkably warm and comfortable, and entirely exclude all damp.”

At Lancaster, Eden noted: ‘Ironed clogs, which are much cheaper, more durable, and more wholesome than shoes, are very generally worn by labouring people’.

The noise clogs made alarmed those unused to it. In August 1797 Henry Kitt recorded: ‘We were annoyed at first by the harsh clatter made by the clogs of the boys playing in the street … We were soon, however, convinced that these wooden shoes, capped with plates of iron, were well adapted to the use of the peasants who inhabit a rough and marshy country’.

Sources

Frederick Morton Eden, The State of the Poor, vols. I & II (1797)

Henry Kitt, Kitt’s Tour to the Lakes of Cumberland and Westmorland, vol. 5 (1797)

Cumbria Record Office, Carlisle

PR10/100/18, Skelton Overseers’ Voucher, An account of Grace Matthews clothes and goods, 2 June 1785

PR36/v/2/49, Wigton Overseers’ Voucher, 6 December 1771

PR V/36/3, Wigton Overseers’ Voucher, Thomas Watman 1773

Staffordshire Record Office

D1149/6/2/3/93, Darlaston Overseers’ Voucher, 19 October 1818

D3891/6/34/9/018, Uttoxeter Overseers’ Voucher, 2 September to 18 December 1829

D3891/6/36/8/12, Uttoxeter Overseers’ Voucher, 10 July 1830