Ann Keen’s listings in trade directories from 1818 to 1851 and her listing in the 1851 Census as a boot and shoe dealer (mistress) belies the notion of the short-lived female-owned business.

Ann Keen was born to William and Mary Keen in Eccleshall, Staffordshire, and baptised on 30 December 1771. She died, unmarried, in 1853, and was buried at Christ Church, Lichfield.

Parson and Bradshaw’s 1818 directory lists a William Keen, ironmonger, grocer, druggist and tallow chandler, with premises in Eccleshall’s High Street. By this date Ann Keen was already established as the proprietress of a shoe warehouse in Market Street, Lichfield. She was one of two female shoe dealers listed in the town; the other being Margaret Pinches of Boar Street. In comparison, ten male boot and shoemakers are listed.

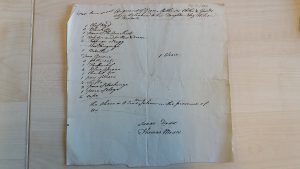

Thus far 11 bills covering the period 1822 to 1829 have been discovered linking Ann Keen’s business to the overseers of St Mary’s, Lichfield. More may come to light. She was supplying men, women and children with ready-made shoes rather than making them. The vouchers show that Ann was assisted by Catherine Keen. What relation Catherine was to Ann is not clear at present, although Catherine might have been the daughter of Ann’s brother Walter baptised in Eccleshall on 31 March 1769. Until Catherine’s Keen’s marriage in 1823, it was Catherine who drew up the bills for the supply of shoes and took payment from the overseers. Following Catherine’s marriage to Moses Smith, a tobacconist from Hanley, Staffordshire, Ann initially employed an assistant J. Beattie, who like Catherine drew up the bills. Later, Ann took to signing the bills herself, or they were initialled by ‘WB’. At the time of the 1851 Census Ann Keen was living on her own in a property on the south side of Market Street.

Catherine’s marriage to Moses Smith was relatively short-lived. Smith died in 1831. By his will Catherine inherited all his stock-in-trade, money, securities for money, debts household furniture, plate, linen, chattels, and personal estate and effects, upon trust during her natural life. His unnamed children (a son and daughter) were to inherit on Catherine’s death. Catherine Smith and George Keen (Moses Smith’s brother-in-law and assistant in his tobacco business) were appointed the executors. An entry in White’s 1834 directory shows that Catherine continued her husband’s business as a tobacconist in Slack’s Lane, Hanley.

Sources

Staffordshire Record Office

BC/11, Will of Moses Smith of Hanley, Staffordshire, proved 7 March 1832

D20/1/11, St Mary’s Parish Register, Lichfield, 30 June 1823

D286/2/11, Christ Church Parish Register, Lichfield, 9 July 1853

D3767/1/5, Holy Trinity Parish Register, Eccleshall, 31 March 1769, 30 December 1771

LD20/6/6/21, Lichfield, St Mary’s Overseers’ Voucher, Ann Keen, settled 18 June 1822

LD20/6/6/, no item number, Lichfield, St Mary’s Overseers’ Vouchers, 14 August 1822, 25 June 1825, one undated [1825], and 29 June 1826, for example

TNA, HO107/2014, 1851 Census

Parson, W. and Bradshaw, T., Staffordshire General and Commercial Directory presenting an Alphabetical Arrangement of the Names and Residences of the Nobility, Gentry, Merchants and Inhabitants in General (Manchester: J. Leigh, 1818), 165, 175, 184, 188, 189

White, William, History, Gazetteer and Directory of the County of Staffordshire and of the City of Lichfield (Sheffield: 1834), 157, 569

White, William, History, Gazetteer & Directory of Staffordshire, 2nd edn. (Sheffield, printed by Robert Leader, 1851), 5