Written by Denise, posted by Alannah

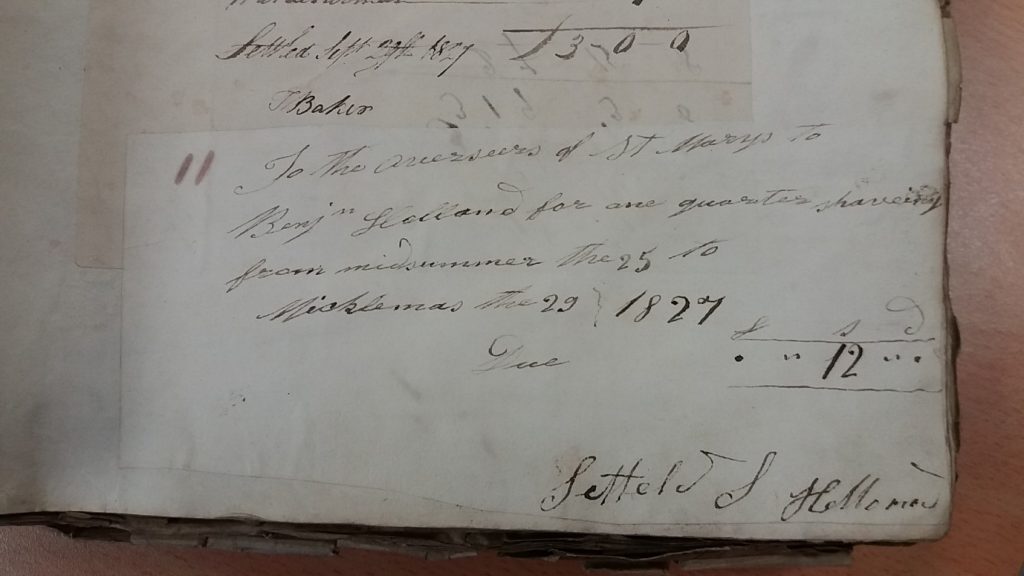

Intrigued when examining two Poor Law vouchers for Aldridge, Staffordshire, which mentioned the trial of “the three Morrises”, my research revealed two brothers were both transported in 1819 to Australia for 7 years for Larceny (Theft).

Included in the description of costs claimed by Constable James Wakeman in a voucher (receipt): “Prosecution of the Three Morris’s” are various journeys and duties commencing 7 Jan 1818, including: taking Thomas Morris at Aldridge, executing two search warrants, attending his prosecution at Shenstone, using a chaise to take the prisoner to Stafford Prison, bringing the prisoner home from [West] Bromwich, journeys of witnesses, a journey to “West Bromwich and Wednesbury to take Mrs Morris”.

Included in the invoice for legal costs incurred on 13 March 1818 by attorneys Messrs Croxall and Holbecke, were costs “Instructions for Brief and preparing same against Thomas Morris on the prosecution of Samuel Boden, the like against Hannah, Thos and John Morris on the prosecution of Sophia Rogers…” and then on the same date “attending at Stafford conducting these prosecutions when Thomas and John Morris were transported”.

My research revealed Thomas and John Morris were born and baptised in West Bromwich, Staffordshire in November 1793 and October 1790 respectively to Hannah (nee Sheldon, 1764-1823) and James Morris (1765-1836). There were at least four other siblings, Elizabeth, Mary, James and Anne, in the family with ancestors that can fairly easily be traced back to the seventeenth century.

Reports in The Staffordshire Advertiser revealed Thomas was tried at the Stafford Lent Assizes in March 1818 for the theft of a goose and a gander, whilst John and their mother Hannah were tried for “various other felonies”. Hannah was acquitted but John was found guilty of the “theft of wearing apparel” and was sentenced to 7 years Transportation along with brother Thomas.

It seems unlikely that the brothers were sentenced to transportation on first offences but with criminal records at that time usually only quoting names, and not ages or addresses, it is not possible to confirm what other offences might have been committed. Transportation for 7 years seems to be the customary, albeit harsh, sentence for those convicted of larceny.

They remained at Stafford Gaol until being removed, along with 19 other convicts under sentence of transportation, to the hulks (holding prison ships) at Sheerness, Kent. They did not leave England until 14 June 1819 when they sailed to Australia on the “Malabar” with 168 other convicts, arriving at Sydney, New South Wales, on 30 October 1819.

Various convict records describe the two brothers: Thomas was 27 years old, a locksmith and was 5ft 5 ½” with a “dark pale” complexion, black hair and hazel eyes. John was 29, a pistol maker, and shorter at 5ft 3 ½”, with a “dark pale”complexion, brown hair and grey eyes with a blemish in the right eye.

They appear to have served out their sentence in Sydney and remained there when granted Certificates of Freedom in March 1825, with Census records indicating they were living together in Market Street, Sydney, in 1828; Thomas was now a gunsmith and John a barber. There are no apparent records of Thomas marrying or having a family although John secured permission to marry a Bonded Convict (still serving her sentence) in 1829, Catherine Richardson, who had also been sentenced to 7 years Transportation for “Coining” (passing counterfeit coins), arriving on “Competitor” the previous year.

Catherine died in 1842 and there are no records of their children, although John seems to have fathered a daughter with an “Anne D” according to other ancestry trees in 1850.

Both brothers stayed in the Sydney area, Thomas dying aged 56 years in 1850 and John in 1868, aged 78 years. It is unlikely that they would remained in contact with their family in West Bromwich, Staffordshire, so would have been unaware that father James died in 1836 and their mother, Hannah, in 1823. Their only brother James seems to be more law-abiding, residing with his wife and family in West Bromwich and employed as a pistol filer until he died in 1860.

Sources of Information:

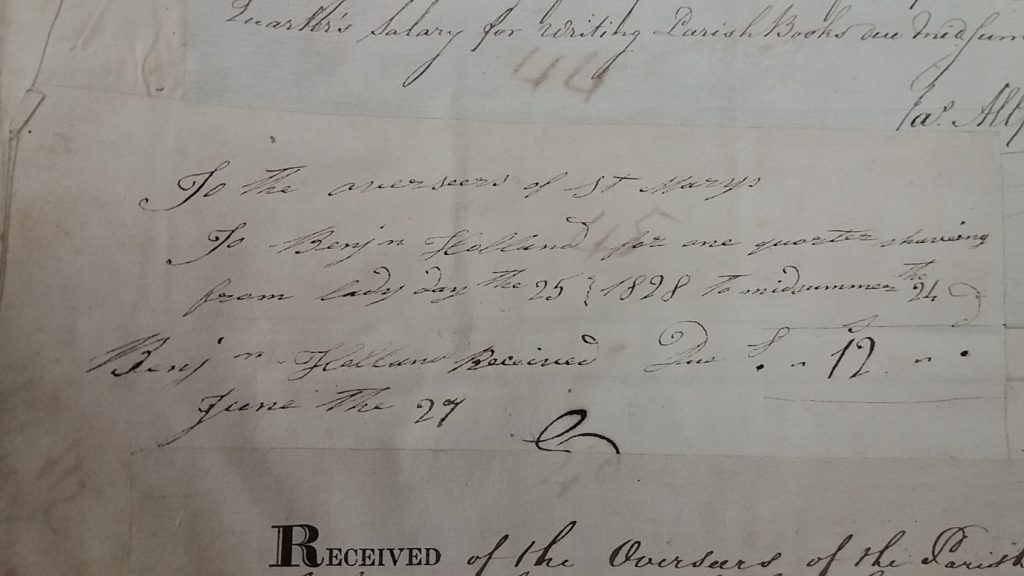

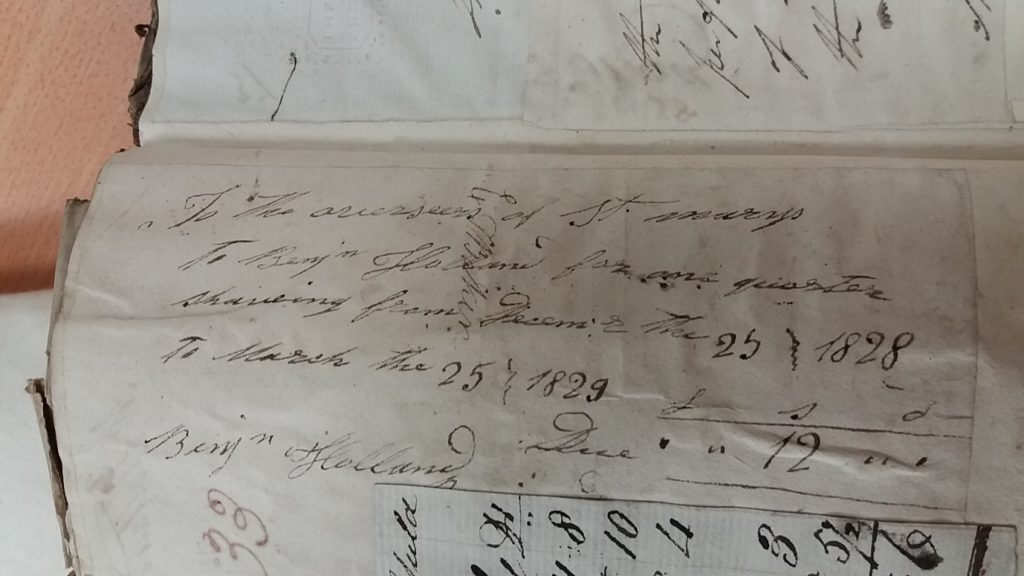

SRO D120/A/PO/102, Aldridge Overseers’ Vouchers dated 15 Mar 1818

SRO D120/A/PO/103, Aldridge Overseers’ Vouchers dated 1818

England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975

England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892

New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents, 1788-1842

Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791-1868

New South Wales, Australia, Convict Applications for the Publications of Banns, 1828-1830, 1838-1839 New South Wales, Australia, Convict Records, 1810-1891

Australia, Marriage Index, 1788-1950

1828 New South Wales, Australia Census (Australian Copy)

New South Wales, Australia, Historical Electoral Rolls, 1842-1864

New South Wales, Australia, Certificates of Freedom, 1810-1814, 1827-1867

Australia, Death Index, 1787-1985

Australia, Birth Index, 1788-1922

Ancestry Family Trees