George Haslehurst, born in Eckington, Derbyshire, c.1792, probably the son of George Haslehurst of Eckington a nailer who, in 1791, had been fined £20 for poaching (reduced to £10 on appeal). He first came to attention through the surviving overseers’ vouchers of the parish of Uttoxeter, Staffordshire. Subsequent research had uncovered a complex life of multiple marriages, infant deaths and criminal activity.

On 10 September 1821 he married Hannah (I) Wood (c.1800–22), a spinster, at St Mary’s parish church Uttoxeter. The witnesses were James Appleby and Thomas Osborne. It was a brief marriage as Hannah died and was buried on 4 February 1822. George was not a widower for long, for he married for a second time on 22 October 1822. His wife was Hannah Cotterill (née Appleby), the recently widowed wife of Thomas Cotterill (1795–1821). Their marriage had taken place on 17 April 1820 and had as been equally brief as George and Hannah Haslehursts’. It is interesting to note that one of the witnesses of the Cotterill marriage had been Thomas Osborne.

George and Hannah (II) had a son Thomas born 8 February 1823, either meaning a very premature baby or Hannah (II) had become pregnant very soon after the death of George’s first wife, Hannah (I). Thomas was baptised at Uttoxeter’s Wesleyan chapel. He died aged four months in early June 1823. A Mary Haslehurst, possibly George’s and Mary’s second child, was buried in Uttoxeter on 23 June 1823, aged three months. In 1827 a third child, Elizabeth was born and in April 1831 a fourth, Mary, who survived for eleven months and was buried on 8 March 1831. It is likely that the birth of Mary led to Hannah’s (II) death on 4 June 1830, aged 31.

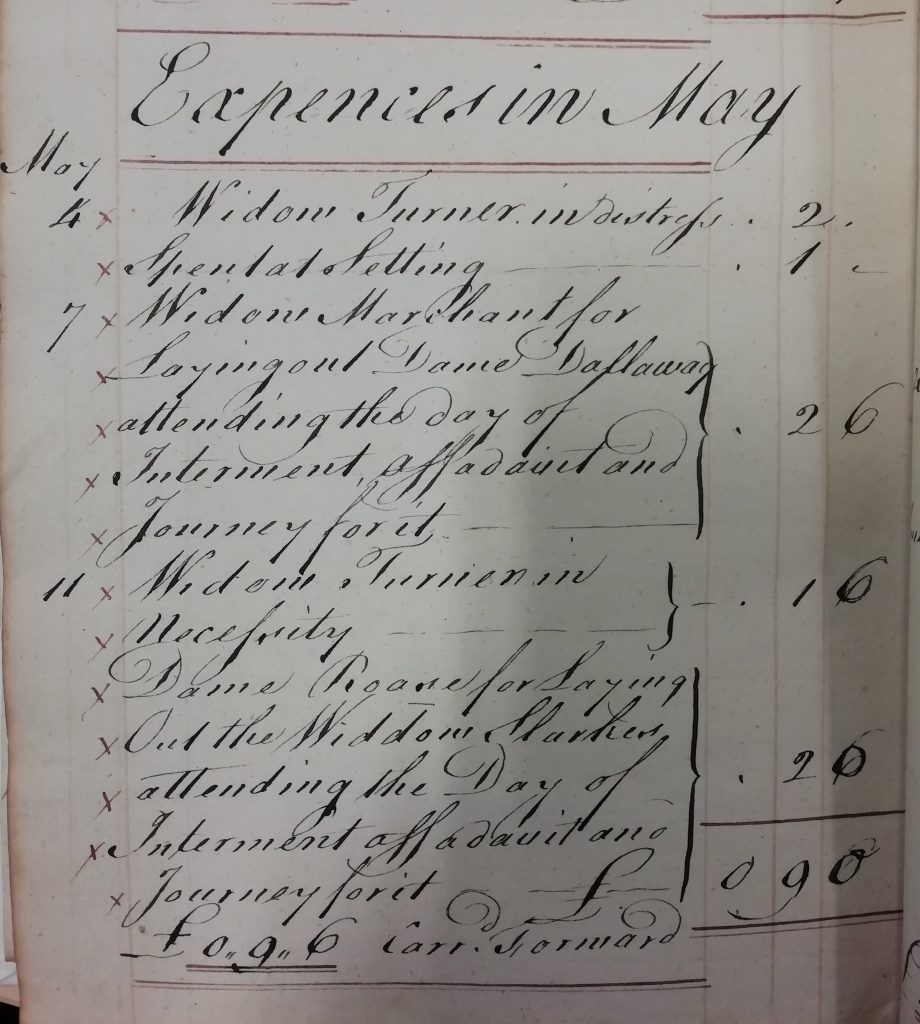

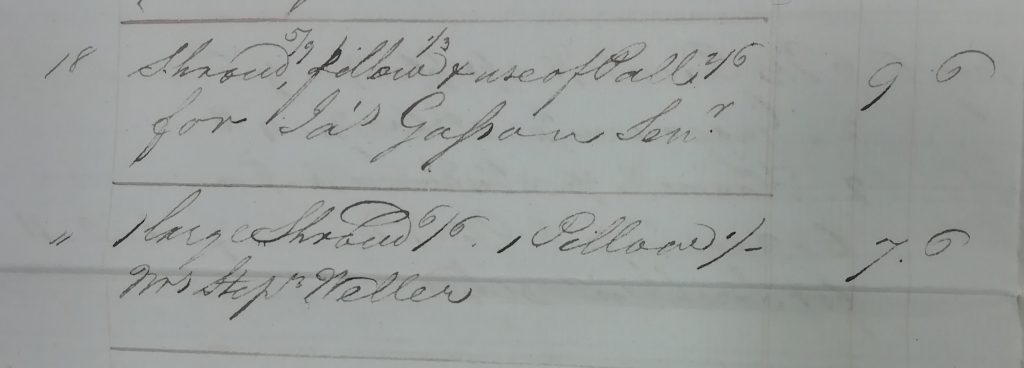

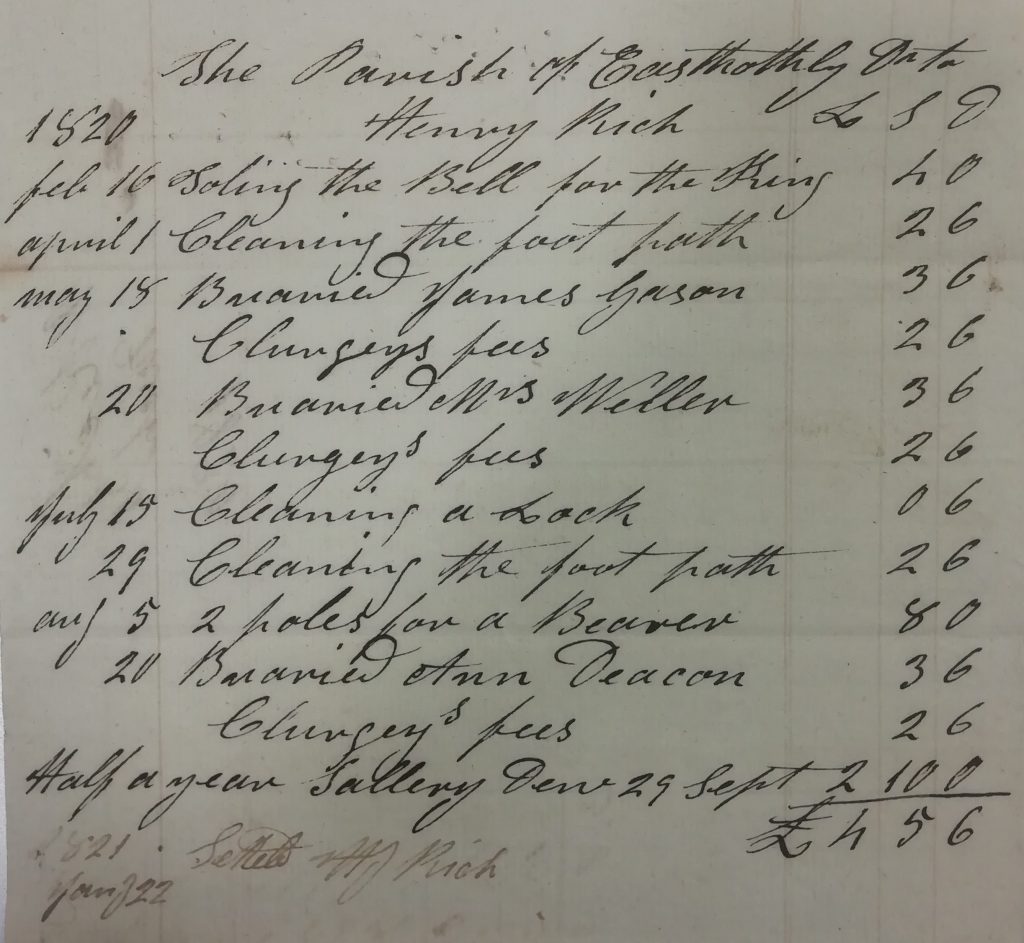

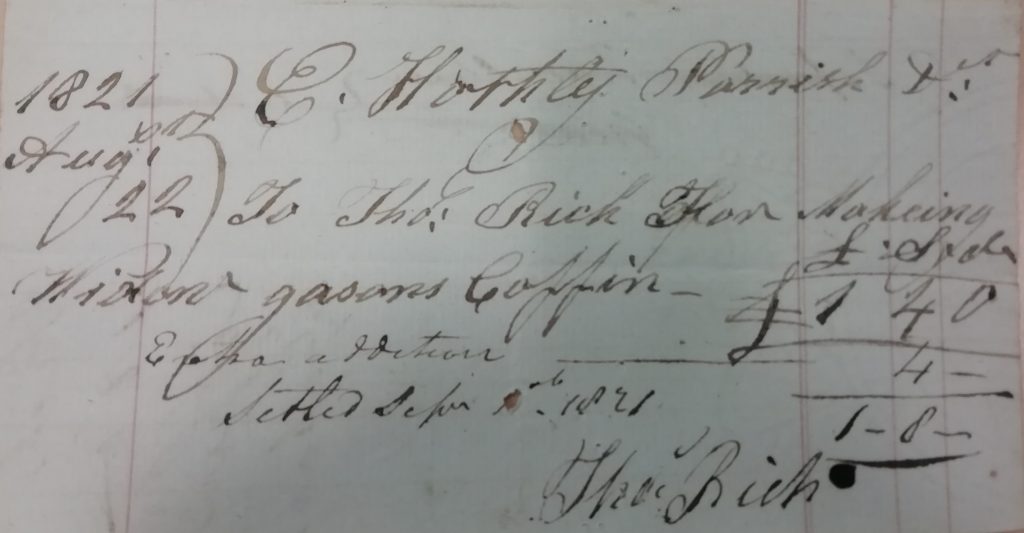

It is at some point after this that Haslehurst and the administrators of the Poor Law for Uttoxeter came into contact with each other. In April 1831 George Haslehurst was served with a removal order and was taken with his surviving child Elizabeth to Eckington by William Williams. Williams charged the parish £2 8s for his services. In May 1831 two vouchers relating to Haslehurst show that Elizabeth had died, a coffin had been supplied by Goodall and Heath and that Uttoxeter had paid for the child’s burial.

For the next fifteen years nothing further is heard of George Haslehurst until just before his third marriage. In January 1846 the Derbyshire Advertiser reported that George had been found guilty of being drunk and of assaulting Robert Yeomans of Ashbourne. He was fined for both, and in default of payment was to be committed to gaol for 24 days. His conduct did not prevent his marriage to Fanny Overton (née Baker), a widow with one son Enoch from Ashbourne. The marriage took place at St Oswald’s, Ashbourne on 28 March 1846.

It is also possible that this George Haselhurst was the same George Haslehurst, aged 53, who was up on a charge of larceny, but subsequently acquitted, at the Derby County sessions in January 1844.

By 1851 George, aged 59, and Fanny, aged 57, were living with Enoch Overton in Bunting’s Yard, High Street, Uttoxeter. However, it also seems likely that George once again found himself at odds with the law, and this time it was far more serious. In July 1854 the Derby Mercury reported the trial of George Hazlehurst, aged 62. He was charged with indecent assault upon Elizabeth Marsden a seven-year-old infant. The incident had occurred on the 1 May 1854 at Barlborough, a place close to Eckington. The newspaper thought evidence unfit for publication. The jury found him guilty of the intent and he was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment with hard labour.

George died sometime between 1854 and 1861. The 1861 Census shows that Fanny Haslehurst, now 67, a widow and infirm was still living in High Street, Uttoxeter.

Sources

Derbyshire Record Office, St Oswald’s Parish Register, Ashbourne.

Derby Mercury, January 1844, July 1854.

Derbyshire Advertiser, January 1846.

1851 and 1861 Census Returns

Staffordshire Record Office,

SRO, D3891/6/37/1/20; D3891/6/37/2/18; D3891/6/37/2/23; D3891/6/37/2/24; D3891/6/37/2/30; D3891/6/37/3/26, Uttoxeter Overseers’ Vouchers.

St Mary’s Parish Register, Uttoxeter.

Uttoxter Wesleyan Chapel Register

wirksworth.org.uk

This is a work in progress, subject to change as new research emerges.