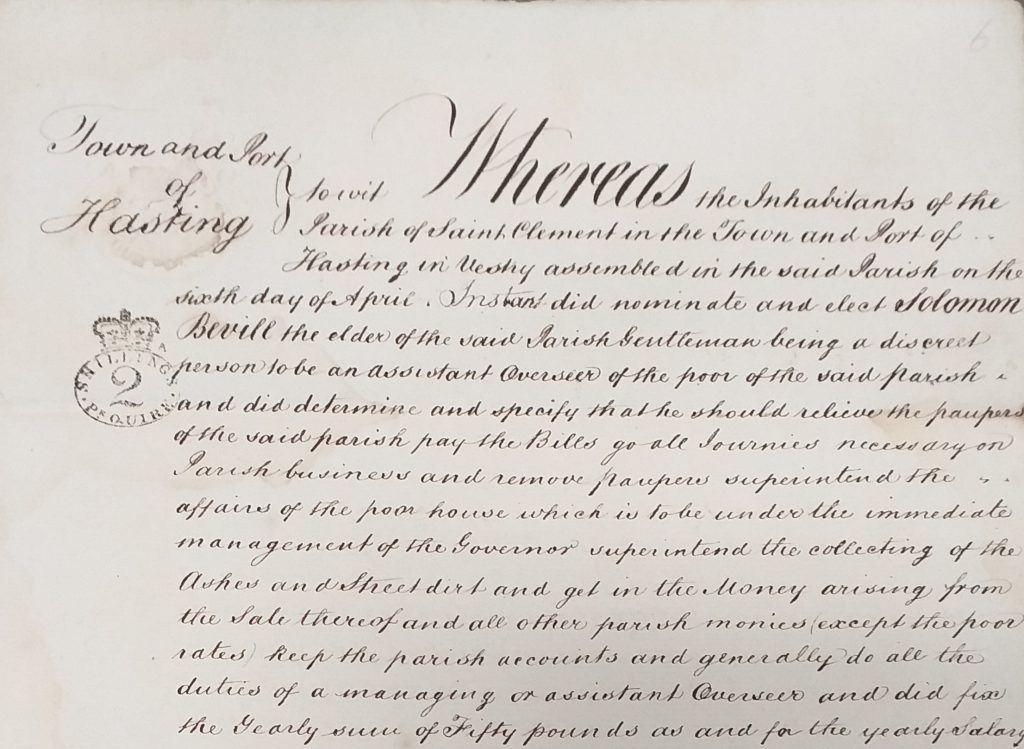

In December 1827, the parish of St Clements in Hastings decided that it was ‘absolutely necessary’ to appoint an assistant overseer. This salaried official would be asked to take over all of the day-to-day drudgery associated with relieving the poor, namely to relieve all paupers, pay all bills, superintend the management of the poorhouse under the governor, removal all paupers and do all the other duties of a managing overseer. This freed the annually-elected overseers to do the really important work of collecting the poor rates.

Candidates for the office wrote to the parish in early April asking to be considered, but they had been pipped to the post by the interim ‘internal’ candidate. Mr Solomon Bevill had been provisionally appointed in January 1828. He remained in post subject to annual reappointments until 1833 when (presumably) declining health prompted him to retire. Bevill died in 1834, leaving goods and property to his children and grandchildren.

Thus far, Bevill’s story fits with the outline for a number of assistant overseers around the country. Men of apparently declining fortunes or towards the end of life secured this sort of post to provide an income in otherwise lean years. What is surprising is the additional detail we can glean from genealogical and other sources about the career that was coming to an end in Bevill’s case.

He had been born in the mid-eighteenth century and was therefore in his late 70s when he took on the parish job. Solomon Bevill was married to Lydia Blackman in 1775. In their early lives, the family members were sufficiently poor to warrant the attention of parish officers: Solomon, Lydia and their daughter Elizabeth were the subject of a settlement certificate issued in 1777. Thereafter their fortunes lifted: Solomon Bevill the elder acquired property in Hastings, and either he or his son, Solomon Bevill the younger, became Comptroller of the Port of Hastings. Most intriguing of all, one of the Solomons (I’m assuming the elder) can be found listed as the commander of a privateer in 1812, during the war against America. A letter of marque was made out to this name as the Commander of the ship Eclips out of Hastings, owned by Thomas Mannington.

Elderly though he may have been, Bevill certainly brought something of a swashbuckling approach to parish affairs. At first appointment, and without asking the vestry, he summarily pulled down the wash house attached to the parish poor house and began rebuilding it with contractors of his choice. The tone of the vestry minutes in recording this realisation is, though, quite conciliatory rather than reproachful or outraged. Presumably Bevill’s long history in the town, or his age, conferred a protective veneer.

Sources: The Keep, East Sussex Record Office: PAR 367/12/2/8, Hastings St Clement Minutes of the Vestry concerning the poor 1827-33; PAR 367/12/5 Hastings St Clement vestry minute book 1823-58; PBT 1/1/78/562; National Archives HCA 25/206.