The Cumberland vouchers make frequent reference to the purchase of blue duffle.William Beck’s The Drapers’ Dictionary cites Booth’s Analytical English Dictionary of 1835 which describes duffle as ‘a stout milled flannel, but of greater depth and differently dressed. It may be either perched or friezed (napped), and is sold in all colours’. The name is generally thought to have derived from Duffel (now in Belgium).

In The Compleat English Tradesman Daniel Defoe notes that ‘The manufacturing towns of Lancashire, Westmorland and Cumberland is employ’d in the coarser manufactures of those counties, such as Kersies, half-thicks, yarn stockings, Duffelds, Ruggs, Turkey-work chairs and many other useful things’.

What was the blue duffle being used for? In all likelihood it was used to make coats or cloaks for the poor, perhaps as a type of uniform for the workhouse, or as part of a set of clothes provided for parish apprentices. Joan Lane notes that clothing for apprentices, including particular items that identified them with specific trades, was a common requirement, and that factory apprentices were expected to attend church looking reasonable. She continues that male parish apprentices ‘received a shirt, waistcoat, breeches, stockings and shoes, with a coat and hat for outdoors. A girl was given a petticoat, one or two shifts … with a gown, apron, stockings and shoes … Coats and cloaks were hardly ever bought for female pauper apprentices’.[1]

Five news items provide further information on the uses of blue duffle:

Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Advertiser, 14 March 1787, described how John Bell, aged 17 or 18, had run away from his apprenticeship from shoemaker George Sugding, in Workington. He was wearing a turned blue coat and vest, black breaches and a woollen hat. At the same time another apprentice, Jonathan Atch, aged 17, also absconded. He was wearing a blue upper jacket, a double-breasted blue vest and blue breaches, all duffle.

Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Advertiser, 23 May 1797, detailed the elopement of Daniel Hodgson and Mary Johnston, the wife of James Johnston. Johnston, aged 67, was reported as wearing a white thickset coat, and a blue and white striped waistcoat. Johnston, ‘a stout made woman … pitted with the small pox’, was wearing a a dark stamped gown and bed gown, a brown or blue quilted petticoat, black worsted stockings , a blue duffle cloak, and a black silk bonnet.

Twenty dozen pairs of stockings and ‘some webs of blue duffle and blue worsted stuff’ were stolen from Bridekirk manufactory, Annan. Carlisle Patriot, 14 March 1818.

Carlisle Journal, 7 August 1841, William Dixon gave evidence against John Cope for stealing a jacket belonging to Isaac Sherwin of Aspatria. When apprehended in Maryport, Cope was wearing a blue duffle jacket beneath which was the stolen jacket. Cope was found guilty and sentenced to six months hard labour.

In 1843 the Carlisle Journal reported an inquest. The headless body of a man was washed ashore opposite Eskmeals. The clothing consisted of a blue and white striped shirt, a red flannel shirt, a blue duffle jacket, and white woollen stockings. \lsdpriority

Sources

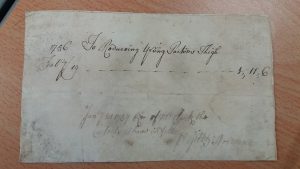

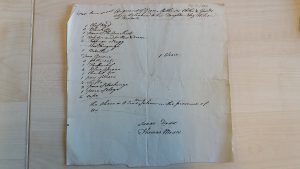

Cumbria Archives Service, Carlisle, PR60/21/13/3/ no item number, Brampton Overseers’ Voucher, settled 31 May 1795

Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Advertiser, 14 March 1787

Cumberland Pacquet and Ware’s Advertiser, 23 May 1797

Carlisle Patriot, 14 March 1818.

Carlisle Journal, 7 August 1841

Carlisle Journal, 9 December 1843

William Beck, The Drapers’ Dictionary: a manual of textile fabrics, their history and applications (London: The Warehousemen and Draper’s Journal Office, 1882), 106

Daniel Defoe, The Compleat English Tradesman vol II, (London: printed for Charles Rivington, 1727), 59–60

Joan Lane, Apprenticeship

in England, 1600–1914 (London: UCL Press, 1996), 27–29

[1] Joan Lane, Apprenticeship in England, 1600–1914 (London: UCL Press, 1996), 29.