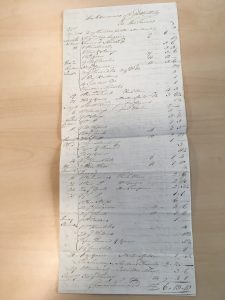

Although most of the documents within the bundles from East Hoathly are small bills and vouchers, occasionally an item comes to light which is a bit different. One such item was a recipe for ‘Millett’ pudding’. It appears to have been written rather hurriedly on the back of a small bill and is probably in Thomas Turner’s handwriting. Just as we might do today, it was jotted down on the nearest piece of paper that came to hand. Maybe it was recommended to Turner by a customer in his shop. It is easy to imagine that moment, a snapshot of everyday life in the Sussex village.

The recipe or ‘receipt’ as it would have been called reads:

Boil the Milk & Millett till it Comes to a proper thickness

2 lb Millett

3 Eges

Sugar

Nutmeg

Equal in the Same as Rice Pudding – but always Backed

The document is rather stained and unrelated notes are written on this scrap of paper. The more official looking list of items on the reverse of the recipe relates to the schoolroom. Sums of money are included and if this had not been a bill for spelling books and testaments, the recipe would probably have been discarded. The list is not headed with a name or signed but a date is written 1782. Other documents in the bundle were from the 1780s.

Why millet? It appears to be offered as an alternative ingredient to rice which was very likely the preferred choice. Both were imported and maybe rice was more expensive.

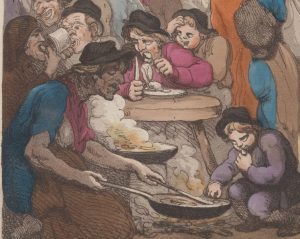

Thomas Turner refers to food and his own diet frequently within his diary. [1] Often this is an account of his dinners. Typically he writes: ‘We dined on the remains of yesterday’s dinner……’

Turner appears to be very interested in new ideas for recipes, particularly those including cheaper ingredients, so relevant at a time when staple foods were scarce or expensive, especially to the poor of villages such as East Hoathly.

On Fri 27 Jan 1758, he quotes in his diary from The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, [2] to which Turner probably subscribed.

At home all day. We dined on the remains of Wednesday and yesterday’s dinners with the addition of a cheap kind of soup, the receipt for making of which I took out of The Universal Magazine for December as recommended (by James Stonhouse MD at Northampton) to all poor families as a very cheap and nourishing food. The following is the receipt, viz.,

Take half a pound of beef, mutton, or pork, cut into small pieces; half a pint of peas, three sliced turnips, and three potatoes, cut very small, an onion or two, or a few leeks; put to them three quarts and a pint of water; let it boil gently on a very slow fire about two hours and a half, then thicken it with a quarter of a pound of ground rice, and half a quarter of a pound of oatmeal (or a quarter of a pound of oatmeal and no rice); boil it for a quarter of an hour after the thickening is put in stirring it all the time; then season it with salt, ground pepper or powdered ginger to your taste.

This in my opinion is a very good, palatable, cheap, nourishing diet…

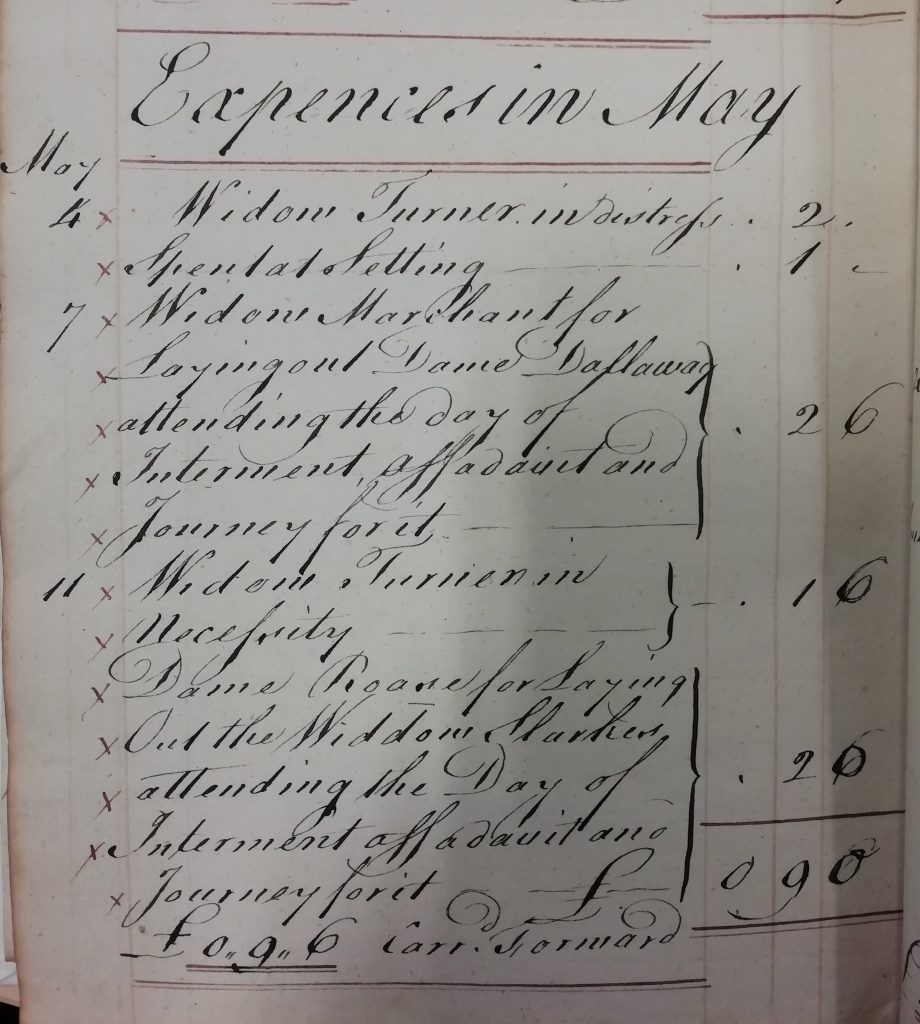

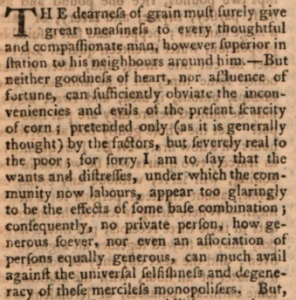

The introduction to this article noted the local ‘distress’ :

Six ‘receipts’ follow including some without meat: a ‘Burgout much used by the Scotch’ (porridge); ‘Leek-pottage’; ‘Potato-bread’, which is recommended as an alternative to corn; and beer made with treacle.

On Thurs. 23 March 1758, Turner describes this ‘melancholy time occasioned by the dearness of corn, though not proceeding from a real scarcity, but from the iniquitous practice of engrossers, forestalling etc.’ In other words, those who buy commodities cheaply but do not release them on to the market until the price has risen to a high level.

Turner follows this by claiming in a somewhat remorseful way, remembering his over indulgences and ‘revelling … being discomposed with too much drink’, that he will ‘be content to put up with two meals a day, and both of them I am also willing should be of pudding; that is, I am not desirous of eating meat above once or at the most twice a week. My common drink is only water …’

Sources:

[1] Thomas Turner, The Diary of Thomas Turner 1754-1765, ed. David Vaisey, 1984.

[2] The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure, Vol. XXI (Dec. 1757), pp. 268-71