Daniel Dunglinson was the governor of Kendal Workhouse, Westmorland, for over 20 years. He was baptised at Crosthwaite, near Keswick, in the adjacent county of Cumberland. His parents were Daniel Dunglinson (1730-1814) and Dinah Fisher (1731-1810). His name can be found on letters and bills sent to Threlkeld parish, four miles from Keswick, between 1805 and 1811 concerning Sarah Sowerby. It is assumed that Sarah’s parish of settlement was Threlkeld and she had not gained any settlement rights in Kendal.

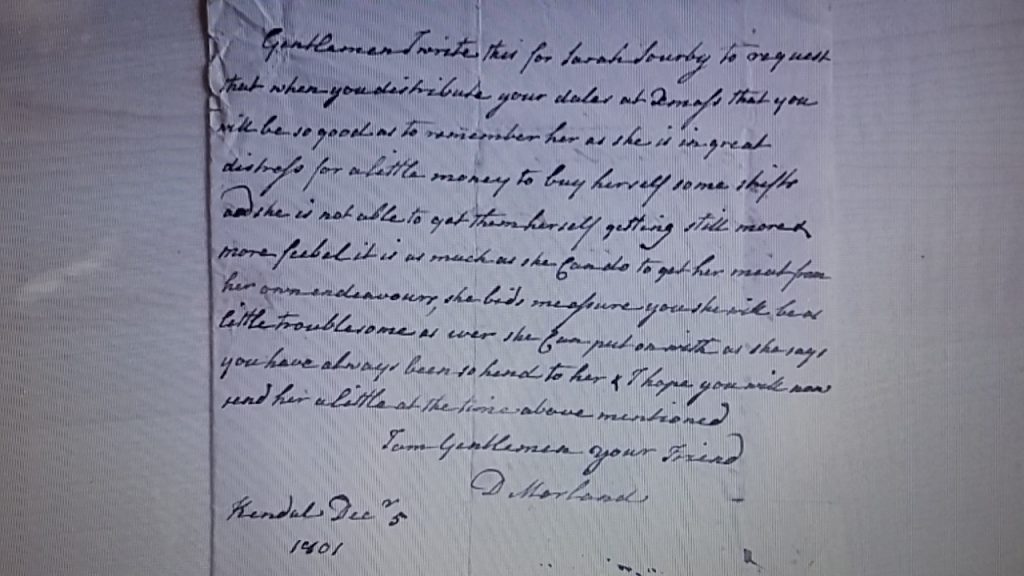

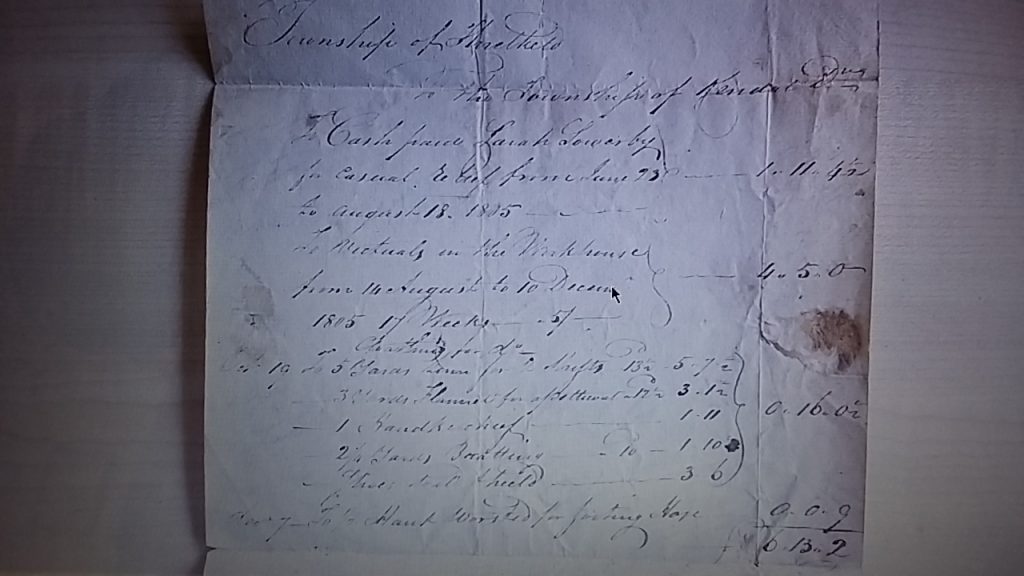

A letter with an attached bill to Joseph Dixon, overseer, in Threlkeld from Daniel Dunglinson reveals that Sarah had become a resident in Kendal Workhouse. [1 ] Expenses for Sarah include £1. 11s. 4 1/2d for casual relief June 23 to August 18 prior to her admission to the workhouse in 1805.[ 2] This was a lot of money. Prior to this, Sarah’s name appears on their St. Thomas’s Day account sheets receiving casual relief of £4. 5s. 0d. in 1801 [3] and in 1803 £0.7s 0d.[4] She found it necessary, however, to ask for further help. A letter written on her behalf (5 December 1801) by D. Morland asks that she be remembered at Christmas as she is more feeble and ‘she struggles to get her meat‘. She hopes something will be sent as kindness has been shown to her in the past. [5]

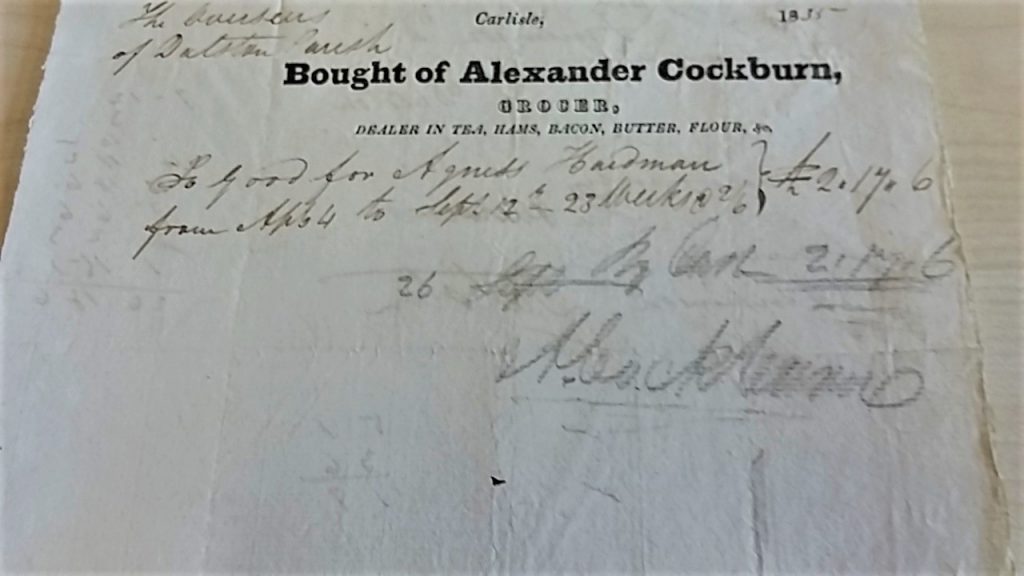

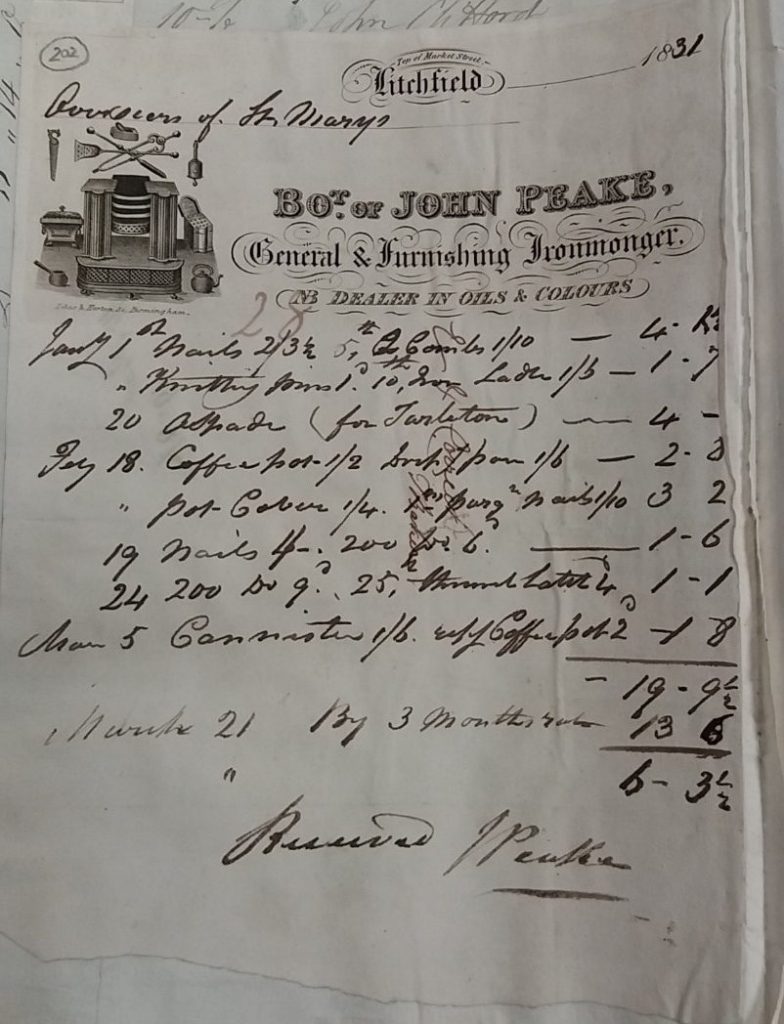

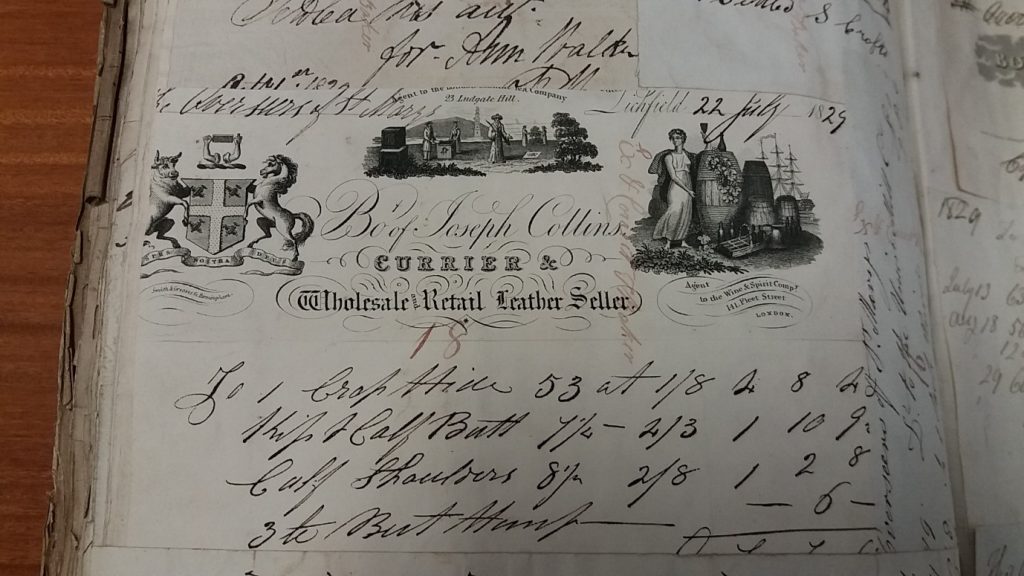

While in the workhouse various requests and payments occur between Kendal and Threlkeld. Typical examples of expenditure for Sarah are:-

May 5 1807 26 weeks board at 3s. 6d. total cost £4. 11s. 0d.[6] Her board for 26 weeks had increased by 7 November 1809 to 4s. a week.[7] Items of clothing and fabrics, for example, a handkerchief, 1s. 11d.; flannel for petticoats, 3s. 1 1/2d.; 2/4 yards bratting, 1s. 10d., 10 December 1805;[8] new shoes, 7s. 6d. 16 April 1807.[ 9] Items requested, 2 brats 1s. 4d., and 2 shifts, 5s. 5d.; 4 August 1807. [10 ]

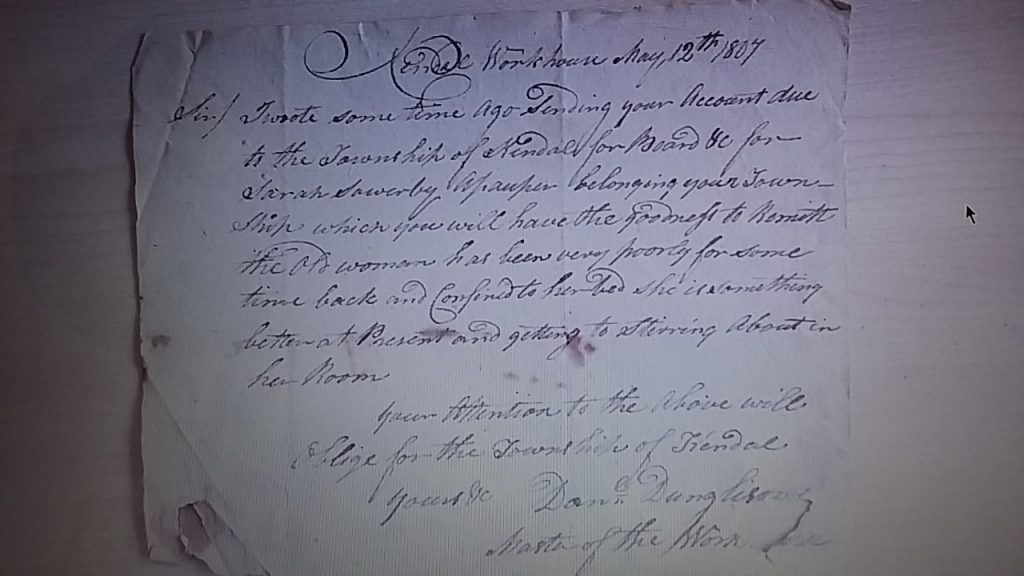

In November 1806 Sarah had been ill but was recovering. By August the following year Daniel Dunglinson wrote ‘the old lady has been poorly for some time back and confined to her bed. She is something better at present and getting to stirring about in her room’. [11] Sarah had been requesting items of clothing for herself. Threlkeld was slow to agree the request as a letter from Thomas Winter overseer in Kendal to Threlkeld December 1807 reveals. He again asks for their agreement to having these items supplied to her [12]

Sarah’s name appears on a bill for a pair of hose and other items on 31 January 1811[13] but is absent from the St.Thomas Day account of 1812. [14] Sarah having died that year, had been a resident in the workhouse for seven years.

Other inmates, if the Kendal Mercury accounts are accurate, were there longer. One example on the 14 May 1836 is given of a Betty Holmes who had been in the workhouse since 1801. A servant in Kendal she had jumped from a window when ‘love crazed her brain’, subsequently losing a leg and never regaining her reasoning. Kindly regarded by charitable ladies of the town, she was allowed to visit them once a fortnight. [15 ] Unlike Betty nothing could be found to give an idea of Sarah’s life before she entered the workhouse. Access to the workhouse day book may give more information. [16]

The vouchers, along with adverts in the newspapers every January from 1821 as a supplier of oats to the workhouse, [17] give an indication of the length of tenure of Daniel Dunglinson at Kendal Workhouse. His wife died in 1828, Daniel died the following year. His obituary (4 April 1829) reads ‘For may years he filled the office of governor of the workhouse with credit and respectability, he was a truly upright honest man greatly respected in society. [18 ] He was at the workhouse either at or just after the inception of the production of hardens [sacking type fabric] at the workhouse in 1801. [19]. See separate post.

Daniel and Mary (Bailey) Dunglinsons children

Of their children, William the eldest was once a weaver, married to Mary Peill. Together they were responsible for Keswick charity houses and the workhouse,[20] Mary carrying on alone after Williams death in 1845. Henry (1793-1817) married Margaret Lindsey and died aged 23 shortly after their first son Daniel was born. Daniel (1795-1797 ) died in infancy. John (1797-1860) is difficult to positively locate. He may have moved to Shoreditch, Middlesex. marrying first Hannah Sharp (c1784-1832) then Dinah Banks (1804-1876). Only daughter Dinah (1799-1887 ) in later life can be found first in Liverpool running a boarding house, then in London. [21]

sources

[1] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 98, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 11 December 1805

[2] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 98, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 11 December 1805

[3] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 22, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, St. Thomas Day Accounts, 1801

[4] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 8, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 1803

[5] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 23, D. Morland, Letter for Sarah Sowerby, 5 December 1801

[6] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 49, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 16 April 1807

[7] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 40, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, May – November 1809

[8] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 98, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, December 1805

[9] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 49, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, April 1807

[10] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 47, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 4 August 1807

[11] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 48, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 12 letter from Daniel Dunglinson, May 1807

[12] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 37, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, Letter from Thomas Winter, December 1807

[13] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 52, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 31 January 1811

[14] Cumbria Archives, SPC21/8-11 98, Threlkeld Overseers’ Vouchers, 1812 St. Thomas’ Day Accounts

[15] Kendal Mercury, 14 May 1836, p.3 col. e

[16] Cumbria Archives, (Kendal) WC/W/1/34, Workhouse Day Book, 1807-1810

[17] Westmorland Advertiser and Kendal Chronicle, 12 January 1823, p.1 col.d

[18] Westmorland Gazette, 4 April 1829, p.3 col.e

[19] Westmorland Advertiser and Kendal Chronicle, 7 December 1811, p. 4, cols, b-c

[20] Kendal Mercury, 28 March 1840

[21] www.ancestry.co.uk

footnote