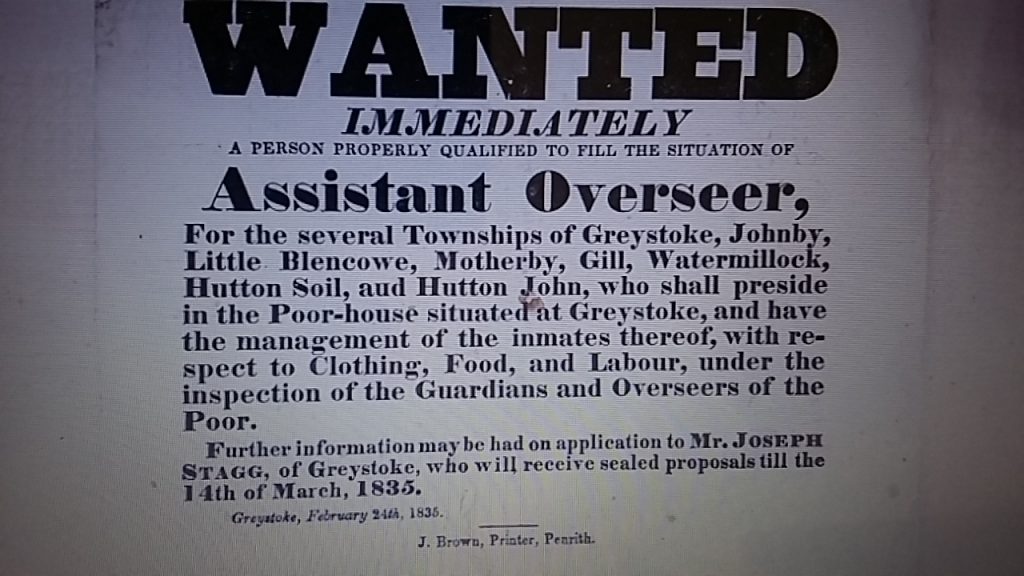

William Miller at one time had a connection to Greystoke Parish but moved to the Durham area with his wife Isabella. No direct narrative is available from the Miller family from 1826 to 1834. The events in their life are told through some of the letters between those involved in the administration of the Old Poor Law in Greystoke, Cumberland, and Wolsingham and Lanchester, both County Durham. William Miller appears to have become so poor that even if he were capable of writing a letter, the cost of postage may have prevented him from doing so.

On 26 June 1826 an epistolary advocate made the case for the Miller family when there was a downturn in the family’s circumstances. Curate Joseph Thompson, writing from The Parsonage, Lanchester, gave an account of what he believed to be the truth of their predicament. He explained that while camping on the roadside for two to three days for the purpose of selling besoms to help pay the rent, a fire not only destroyed their belongings but also burned to death their youngest son John (1825- 1826).

‘As far as I can learn I verify believe it to be correct he had no more than one shilling and sixpence on the morning of the misfortune and since then has been unable to earn anything.’ [1]

Isabella, his wife, although burned, survived as did two other sons Jacob (1821-1830) and James (b.1823). When John was born William Miller was described as a Potter. Thompson went on to explain the misfortune was no fault of their own. Referring to the same incident, Thomas White (1764-1836) of Woodlands, Lanchester, wrote to Thomas Burn. While appearing to illicit some sympathy for the family, he sought a response as they said that they belonged to Greystoke Parish.

‘

‘The poor woman [Isabella Miller] was very much burnt in endeavouring to save the child and the Overseers have of course been at a considerable expense. I therefore write this to state things in order that you may know what to do with these miserable people who say they belong to your parish.’[2]

By 1829 the Millers had another two sons, William (1827-1830) and John George (known as George) (b.1829). William, the father, was described as a besom maker in the parish register. In October the same year they were once again in difficulties. Robert Moses (1774-1841) Overseer of Wolsingham wrote to Thomas Burn attesting that William Miller had no employment, no means to help himself, and the children were much distressed.

‘He has neither Galloway [pony] or Ass to carry them to other markets. The rent due at Martinmass will be £1.12.6’ .[3]

Matters were even worse by 1830. Sons William died on 4 April and Jacob aged 9 died and was buried on 20 July. Another son James (who had been born 24 August 1823) was baptised. A further letter from Joseph Wooler (1776-1865) of Whitfield House, Wolsingham, dated 6 April 1830 makes the case for William Miller being deserving of relief. He was in debt partly as the result of a coroner’s bill for 20 shillings, and described by Wooler as willing to work for as little as 1 shilling a day, having done some work for his son in the Tan yards. [4] Perhaps William and his family were just managing to make ends meets until burdened by the coroner’s bill.

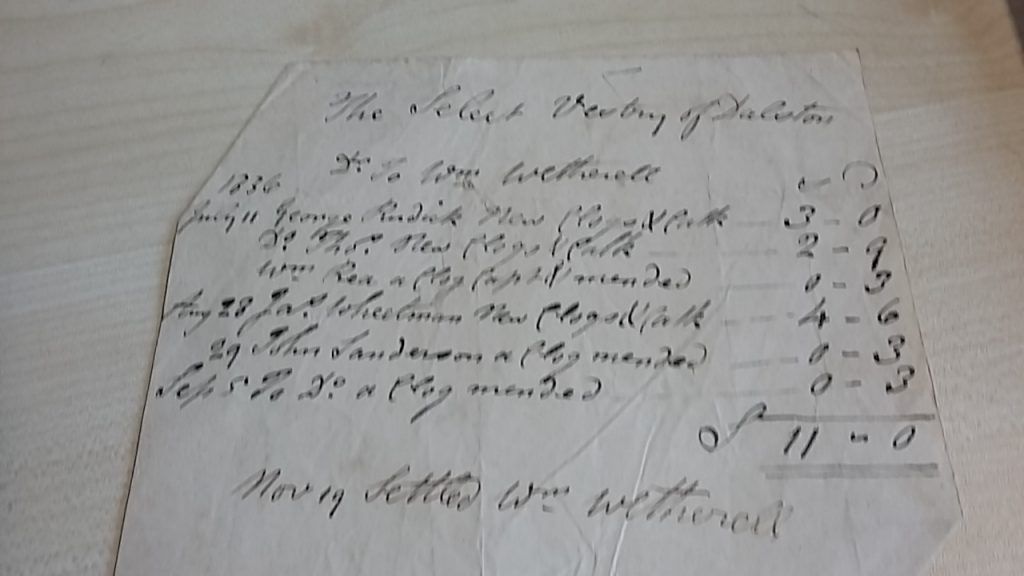

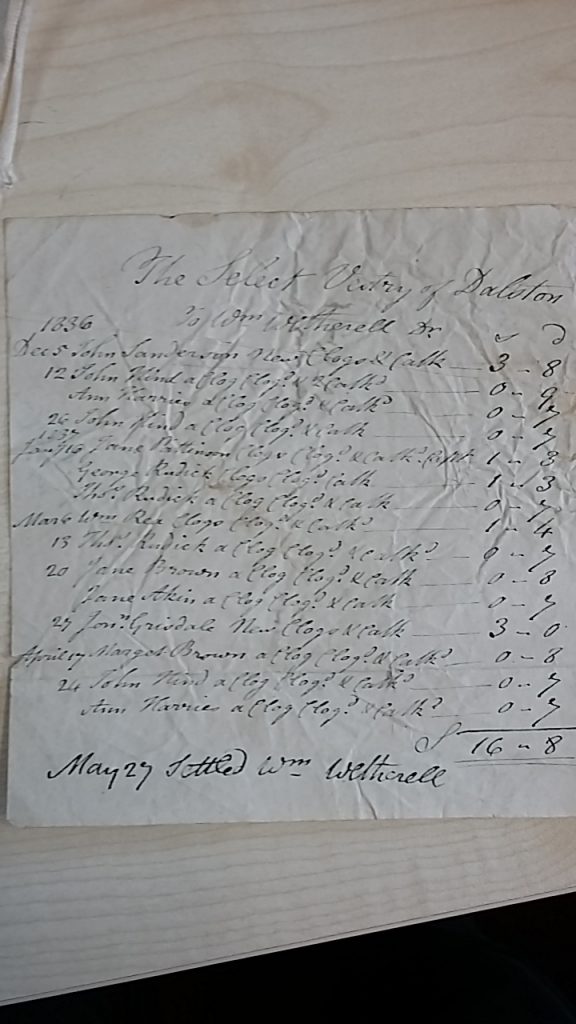

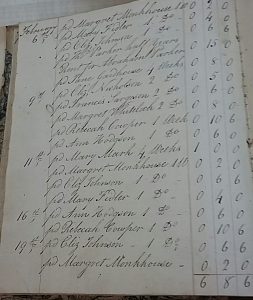

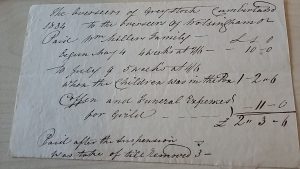

In 1834 William and Isabella were in Wolsingham with four children: James, George [John George] , Mary (b.1833) and Ann Watson (1831–1834). The children were sick with smallpox but were receiving help. Wolsingham acknowledged a receipt from Greystoke for rent: 4 weeks at 2s 6d and 5 weeks at 4s 6d when the family were ill, as well as 11s for a child’s coffin and funeral for Ann being.[5] At this point the registers describe William as a labourer.

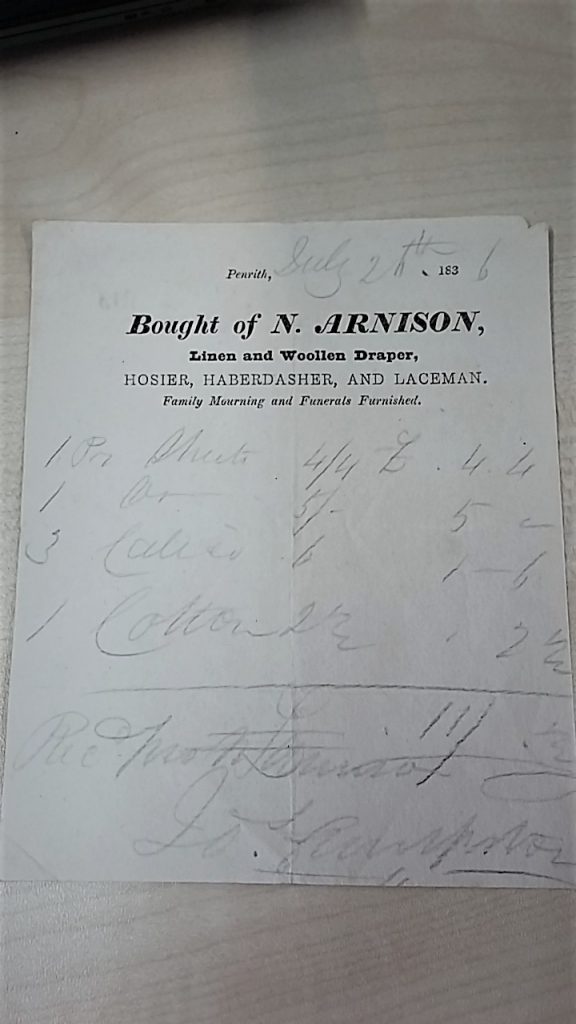

PR 5/67-H 6

When his children were ill with smallpox, William Miller had sought medical assistance , but on the doctor’s refusal to help he then applied to the magistrate, Mr Wilson, who ordered overseer Robert Moses to ask the doctor to attend them.[6] One bill from J Davison, Surgeon, Wolsingham, or £7.14s.6d between April and June 1834 was principally for attending George Miller.[7]

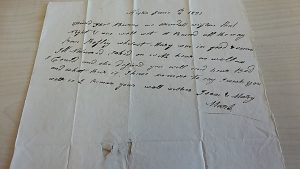

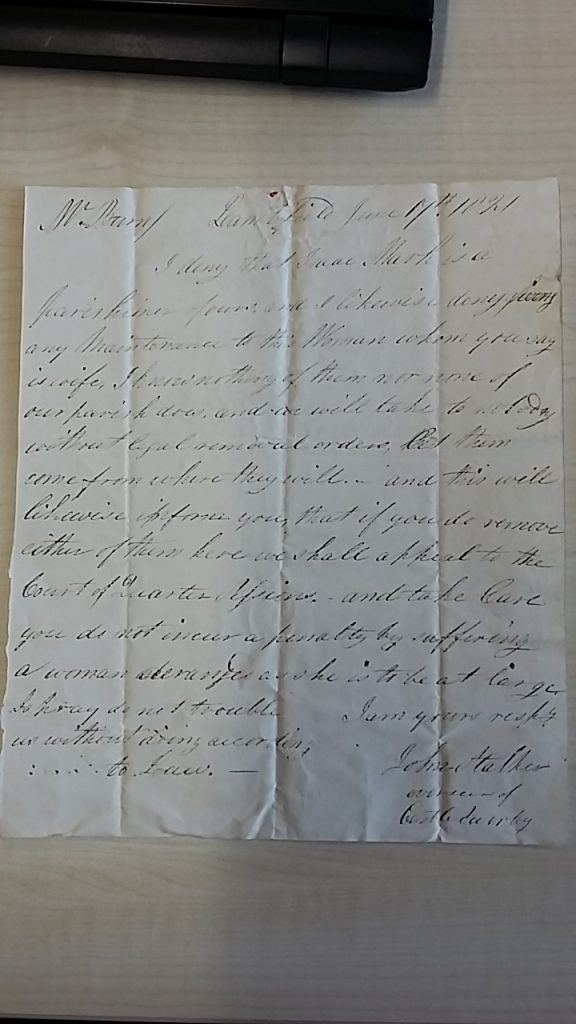

The medical bills became a contencious issue. Robert Moses wrote to Greystoke in May 1834 admonishing Greystoke declaring that, once well, the Millers would be removed if the doctor’s bill was not settled.

‘As you object to paying the bill as soon as the Doctor says the family can be removed I shall send them.’ [8]

He concluded that the Millers’ removal would be welcomed by many of the inhabitants of Wolsingham.

‘ Which are much annoyed by their children begging about the streets.’

A Removal Order was issued by Wolsingham but was suspended in April 1834 due to the families illness. [9] Robert Moses informed Thomas Burn of Greystoke that he had been compelled to issue the order as he had not heard from him for at least a month. [10] Thomas Burn replied on 5 May 1834 saying he had not received a copy of the suspension of the Removal order, so could not pay anything until he did.[11] Robert Moses wrote back three days later with a copy of the order. [12]

‘I do not believe that you are behaving fairly towards me in objecting to pay the Doctors bill.’

The negotiations concerning the doctor’s expenses continued to the point of legal action being proposed by Wolsingham. [13] On 7 October 1834 Thomas Burn wrote to Robert Moses highlighting what Greystoke Parish believed to be discrepancies in the doctor’s bills. He advised Moses that after a meeting of the Vestry he had been ordered to write as they needed an explanation of the costs in the bills. One amounted to £13.4s.0d and the other to £9.18s.0d . The vestry consulted medical men whose opinion was that the bills were too high. [14] In a more conciliatory tone he added:

‘We are bound to go by the law but you don’t we will meet any time upon fair terms.’

The Miller family if they were removed to Greystoke, did not stay. They moved on and became part of the Durham mining community. By 1841 they were in the Parish of St Oswald, Durham. William was a miner living with Isabella and children James, George, Ann (b.1836) and Jacob (b.1841).

The coroner’s bill was paid in 1835 when John Cockburn was Assistant Overseer of Greystoke.[15]

Sources

[1] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/-/F 11.1 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 28 June 1826 (Joseph Thompson to the Overseers of Greystoke)

[2] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/1/F 14.1 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 27 June 1826[7] (Thomas White to Thomas Burn)

[3] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67-I .9 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 29 October 1829 (Robert Moses to Thomas Burn)

[4] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67-J 17 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 6 April 1830 (Joseph Wooler to Thomas Burn)

[5] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 6.1 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 6 May 1834 (Receipt from Greystoke to the Overseers of Wolsingham)

[6] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H2.3 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher 8 May 1834 (Robert Moses to Thomas Burn)

[7] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 10.1-88 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, April – June 1834 (Receipt for Account of J Davison Surgeon)

[8] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H2.3 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 8 May 1834 (Robert Moses to Thomas Burn)

[9] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 18.1 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 28 April 1834 (Suspension of removal order from Wolsingham to Greystoke of the Miller Family)

[10] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 2.2, Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 1 May 1834 (Robert Moses to the Overseers of Greystoke)

[11] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 1 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 5 May 1834 (Thomas Burn to Robert Moses)

[12] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 2 3. Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 8 May 1834 (Thomas Burn to Robert Moses)

[13] Cumbria Archives PR5/67/H 3 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 30 august 1834 (Thomas Burn to Robert Moses)

[14] Cumbria Archives, PR5/67/H 5.1 Greystoke Overseers’ Voucher, 16 September 1834. and PR5/67/H 7.1. 7 October 1834 (Thomas Burn to Robert Moses)

[15] Cumbria Archives, PR5/53, File of Vouchers 1829- 1835

Miller family records accessed at www.findmypast.co.uk Durham, Births Marriage Deaths and Parish Records Durham 4 May 2020