Currier Joseph Collins was born in Claydon, Oxfordshire, in 1795.[1] He was the son of Quakers William and Elizabeth Collins. His father was a farmer.

He married twice. First in 1817 to Elizabeth Vaughton, at St Michael’s, Lichfield; and second, to Elizabeth Langley of Rugeley in 1823.[2] The second marriage took place at St Martin’s, Birmingham, on 22 September 1823.[3]

In 1851 Joseph and Elizabeth Collins, were living in Tamworth Street, with their children, Charles, 23, also a currier; and Emma, 19, an organist; and servant, Mary Beech, 20.[4]

Joseph was not listed in the 1818 trade directory, although gardener and seedsman John Collins was listed with an address in St John Street, and an Edward Collins, of the Fountain Inn, Beacon Street.[5] Two curriers and leather dealers were listed: John Langley in Tamworth Street, and Thomas Langley in Bore Street.[6]

By 1828 Joseph Collins of Tamworth Street had replaced John Langley. Thomas Langley continued to operate from Sandford Street.[7] By 1834 Collins was still in business in Tamworth Street, Thomas Langley had disappeared, and the only other currier listed was William Hughes of Dam Street.[8]

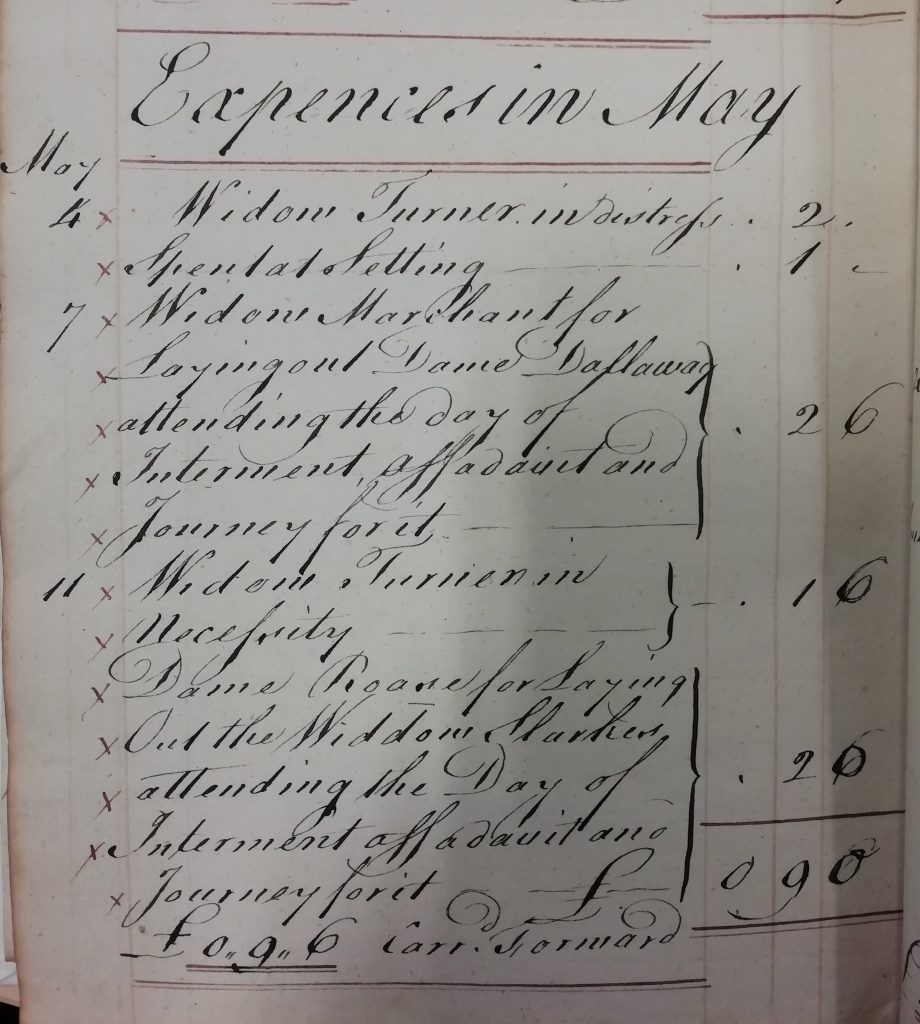

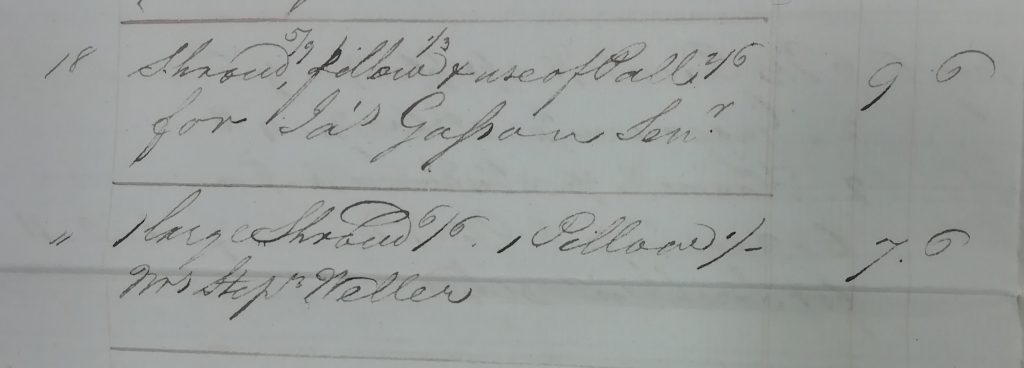

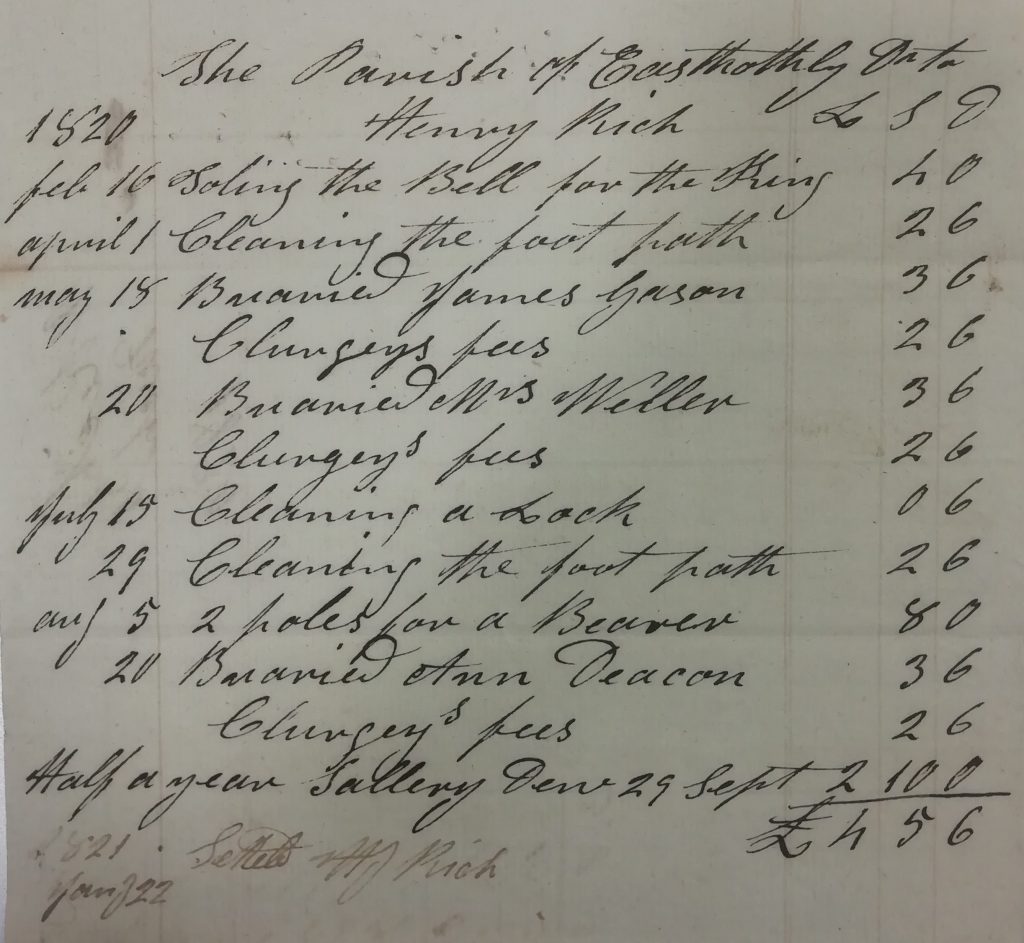

A currier’s job was to process tanned hides which involved a number of processes: cleaning, scraping, stretching and finishing with oils, wax or polish.[9] Collins was also a tea dealer and wine merchant.

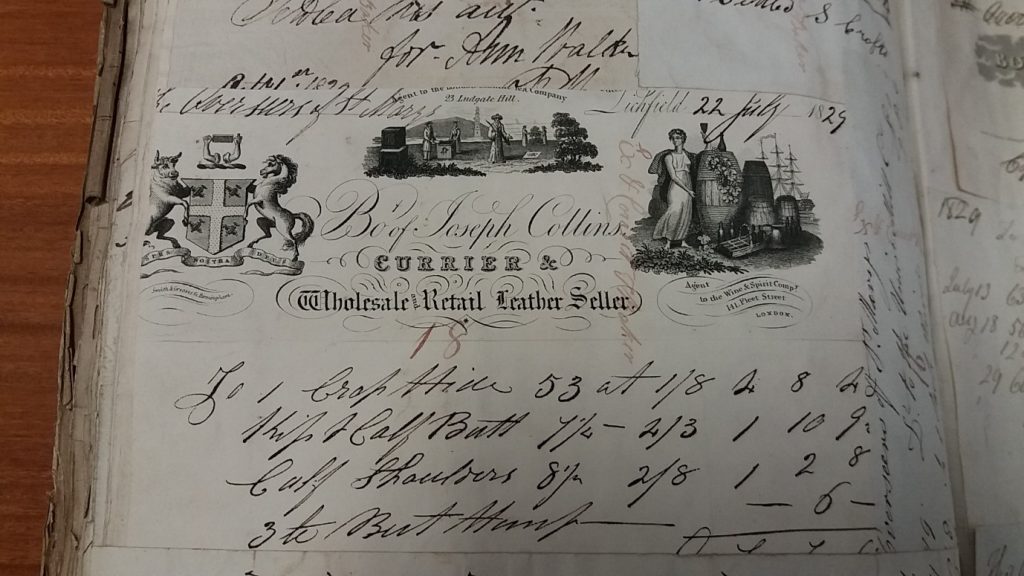

Joseph Collins supplied the overseers of St Mary’s with leather. His bills are elaborately headed with three distinct images.[10] The first shows the armorial bearings of the Worshipful Company of Curriers with its motto ‘Spes Nostra Deus’ (God is our hope). At the top, arms hold up a currier’s shave, and on the shield are four more pairs of shaves.[11]

In the middle is a classic representation of the tea trade: ‘Chinamen’, tea chests, water and a distant ship.[12] Above this are the printed words ‘Agent to the London Genuine Tea Company, 23 Ludgate Hill’. In 1843, the London Genuine Tea Company placed a notice in the Staffordshire Advertiser.[13] Two circumstances had prompted the announcement: growing concern over the adulteration of tea, which they described as ‘disgraceful transactions’; and the ‘peace recently concluded with the Chinese’. The latter had enabled the Company to increase its stock of the finest teas. Eager to promote its ‘pure and unadulterated teas’, it listed its provincial agents, including Joseph Collins of Lichfield.

The third image shows a woman in a classically-inspired dress standing next to a barrel adorned with vines, and grapes. In her hand and she holds up a wine glass. On top of the barrel is a wine bottle and surrounding the barrel are casks, bottles and a bottle carrier. In the background is a three-masted ship. This image reflects the third strand of Collins’ business, that of ‘Agent to the Wine and Spirit Compy, 141 Fleet Street, London’.

In 1835 elections were held in Lichfield. The results created ‘dissatisfaction’ and the episode was reported widely in the press.[14]

The Staffordshire Advertiser reported that the ‘natural quietude’ of Lichfield ‘has not been proof against the excitement of electioneering ardour … Scarcely has the exercise of the parliamentary franchise ever produced so strong a sensation … Squibs, manifestoes, exhortations, and denunciations have succeeded each other with a rapidity unexampled in the annals of the borough-city’. It continued: ‘Two chief parties divided the town. The Elective Franchise Society … held their meetings at the George Inn. A second and mixed party then met at the Old Crown Inn … [who on polling day] made no public display, and indeed many of them declined voting altogether’.[15]

The Sun commented that the Elective Franchise Society, established soon after the last election, ‘has worked wonders … considering how the city had been confined by the Tories previously thereto. The Tories ‘using all the influence that they were possessed of, as well as using their threats of turning several people out of the official situations which they held, if they did not vote according as they were wished’, failed to get the result they hoped for. The Elective Franchise Society proposed 18 reformers; 17 were elected. One of those newly-elected was currier, Joseph Collins. Other suppliers to the overseers of St Mary’s were also elected: Stephen Brassington, John Meacham, and Nicholas Willday. The one remaining place went to a Tory ‘who had ‘the least number of votes’.

The Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser noted that ‘The result of the election has created dissatisfaction and the opponents of the liberals now blame themselves for not having made vigorous opposition’.[16]

[1] TNA, RG 6/34, England and Wales, Society of Friends, Birth 1578-1841, Berkshire and Oxfordshire: Monthly Meeting of Banbury.

[2] SRO, D27/1/18, Lichfield, St Michael, Marriages, 13 April 1817.

[3] Staffordshire Advertiser, 13 December 1823, p.4/3.

[4] TNA, HO 107/2014, Census 1851.

[5] Parson and Bradshaw, William Parson and Thomas Bradshaw, Staffordshire General and Commercial Directory (Manchester: J. Lynch, 1818), p. 170.

[6] Parson and Bradshaw, Directory, p.185.

[7] Pigot and Co., National Commercial Directory [Part 2:] for 1828–29 (London and Manchester: J. Pigot and Co., 1828), p. 716.

[8] William White, History, Gazetteer and Directory of the County of Staffordshire and of the City of Lichfield (Sheffield: 1834), p 158.

[9] The Worshipful Company of Curriers, https://www.curriers.co.uk/history [accessed 26 June 2020].

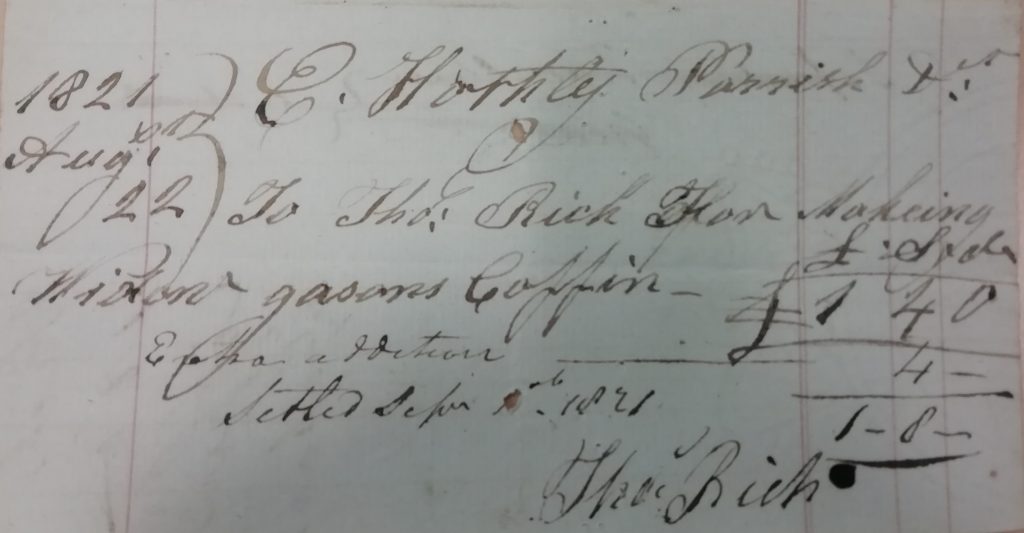

[10] SRO, LD20/6/6, St Mary’s, Lichfield, Overseers’ Vouchers, 22 July 1829; 31 December 1829

[11] https://www.curriers.co.uk/history [accessed 26 June 2020].

[12] Peter Collinge, ‘Chinese Tea, Turkish Coffee and Scottish Tobacco: Image and Meaning in Uttoxeter’s Poor Law Vouchers’, Transactions of the Staffordshire Archaeological and Historical Society, XLIX (June 2017), pp. 80–9.

[13] Staffordshire Advertiser, 25 March 1843, p. 1/3.

[14] Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser, 30 December 1835, p.2/6.

[15] Staffordshire Advertiser, 2 January 1836, p.3/4.

[16] Wolverhampton Chronicle and Staffordshire Advertiser, 30 December 1835, p.2/6.