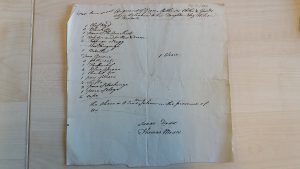

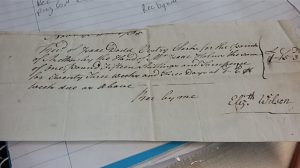

A draper’s bill presented to the overseers of Brampton listed three items as ‘wild boar stuff’. What exactly was ‘wild boar stuff’ and was it really made from ‘wild boar’? ‘Stuff’ was a generic name given to cloth used for making garments. Often the fabric was made from wool, or a mixture of wool and other fibres.

The OED defines ‘hog wool’, as ‘wool from a yearling sheep; the fleece produced by a sheep’s first shearing’. The term originated in the mid-eighteenth century.

John Luccock’s 1809 essay on wool notes, ‘The hog wool, or the first fleece produced by a lamb more than a year old, was greatly esteemed under the old modes of manufacture; and had not the machinery recently adopted rendered it desirable to obtain staples of a uniform length, which is not so easily effected in this class of fleeces, it would still maintain its pre-eminence, as it does in all places where the yarn is spun by hand’.[1] Might this explanation mean that ‘wild boar stuff’ was actually derived from hand spun hog wool?

The Journals of the House of Lords vol. 60 contains a discussion on South Down wool, noting the increase in demand for hog wool: ‘All the Cloth made from the better Sorts of Foreign Wools have a more felting Property in them. That (producing a sample of Worsted Stuff) is made of South Down Hogs, probably South Down and Merinos together.’[2]

One suggestion is that it might be wool from the mangalitsa pig. This long-haired breed was not developed until the mid-nineteenth century by cross-breeding wild boar with Hungarian domesticated pigs, so cannot have been used to make the ‘wild boar stuff’ listed in the draper’s bill. Equally, there seems to be no reference to the use of its fleece for textile production. Another suggestion is that the ‘boar’ might refer to the colour of the textile, or perhaps the texture.

Any further information on ‘wild boar stuff’ would be welcomed.

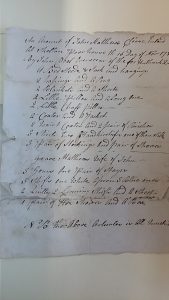

John Styles adds that in Florence Montgomery’s Textiles in America

‘Wildbore’ [spellings varied] is defined as a fairly coarse worsted used for women’s gowns. ‘Stuff’ at this period generally means a worsted fabric, the sort of thing made either at Norwich or in the West Riding.

Sources

William Beck, The Drapers’ Dictionary: a manual of textile fabrics, their history and applications (London: The Warehousemen and Draper’s Journal Office, 1882).

Polly Hamilton, ‘Haberdashery for use in dress, 1550–1800’ (unpublished PhD, University of Wolverhampton, 2009)

Journals of the House of Lords, vol. 60 (1828), Appendix 3

Wilhelm W. Kohl and Peter Toth, The Mangalitsa Pig (2014)

Oxford English

Dictionary

[1] John Luccock, An Essay on Wool, Containing a Particular Account of the English Fleece (London: J. Harding, 1809), 133.

[2] Journals of the House of Lords, vol. 60 (1828), Appendix 3, 84.